How Advent can immunize us against the fear of tyranny

Tyrants extend their power over us by exploiting our natural hopes. Advent divests us of such hopes, by pointing us towards the final triumph of Christ.

Tyrants extend their power over us by exploiting our natural hopes. Advent divests us of such hopes, by pointing us towards the final triumph of Christ.

Advent and preparation for the end of the world

In the previous parts, we looked at the frequency with which the Advent liturgy point us towards Christ’s glorious coming at the end of time. We considered the different attitudes seen today towards Christ’s second coming, ranging from fear to hope; and although both are present in the liturgy, the predominating attitude is one of hope and joyful longing.

It seems that the Church uses the season of Advent to train us in these attitude.

This is quite a different paradigm to one in which Advent is only a catechetical period for telling our children about the Nativity story, reflecting on the state of the world before Christ, and imagining ourselves to be in that time. This is a useful, important and venerable paradigm, but it is not the only one.

This should be clear from our prayers for Christ to come to us: it would be absurd for us to be praying for something that has already happened.

But this focus on the second coming is also different to the other common paradigm, in which Advent and Christmas are about our personal union with Christ by grace. This union is essential to the Christian life, and supremely important for the eternal fate of every human being. Advent makes us focus on this in a special way, through having us meditate on Christ being born into our hearts.

But we must also reckon with the fact that the Church’s liturgy has us call, again and again, for Christ to come to us, in a communal way; and to come in power and majesty.

These calls are not presented as mere imaginative sentiments, but with the urgency of a living, societal reality. The twentieth century liturgical writer Fr Johannes Pinsk expresses this forcefully, saying that the Church’s liturgical prayers “would be nothing more than empty and almost unbearable phrases” if they exclusively referred to the historical birth of Christ; he also insists that they are all too universal, public and communal to refer only to his coming into our individual hearts by grace.1

He writes:

“I cannot admit that for four weeks the Church prepares her priests and faithful in the most intense way for the coming of Christ, making them count the days, keeping them in the strongest tension on Christmas Eve with the opposition of ‘today’ and ‘tomorrow’, if in the end all this would only lead to a change of psychological attitude on our part, to a pretence of going back in time. In any case, the Church must be taken seriously, especially in her prayer.”

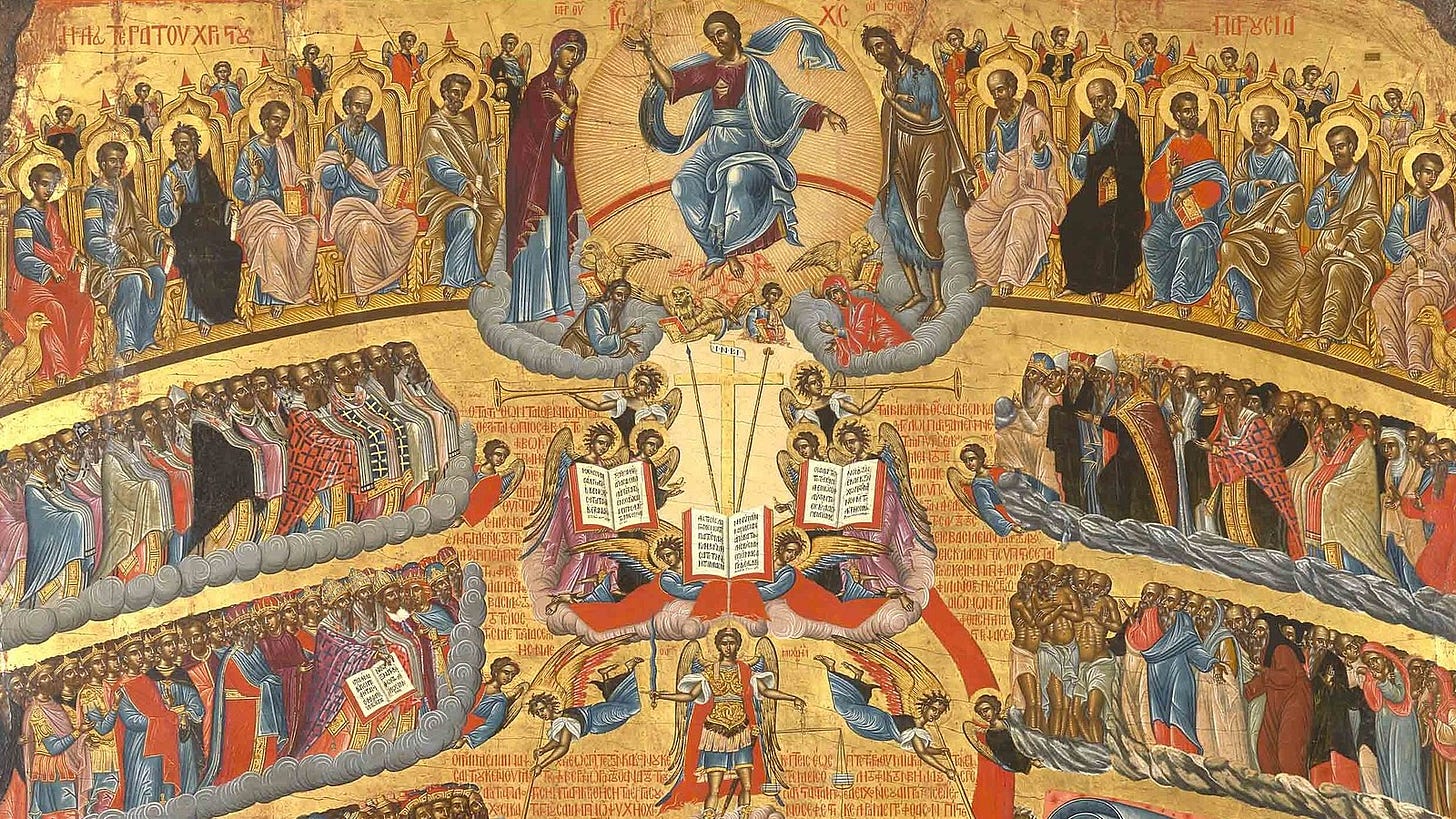

As I have already said, this is not a call for us to replace Nativity scenes with depictions of the Last Judgement. There is nothing wrong with catechising our children, or meditating on the patriarchs, and certainly not with calling Our Lord to come into our hearts. We want all these things, and we are obliged to seek after all these goods—especially the latter.

But we also want something ecclesial and public—the social reign of Christ the King today, as well as his ultimate triumph at the end of the world.

In this vein, let’s consider how an Advent spent in longing for the final triumph of Christ may be a great consolation in our time of crises of Church and state—and how it helps us set aside the many misguided hopes and fears which leave us vulnerable to the wicked.

This is a members-only post for those who support us with monthly or annual subscriptions. It’s a part of our series The Roman Liturgy on the liturgy, and reasons for hope amidst the crisis in the Church.

Our work takes a lot of time and energy. Please consider subscribing if you like it.

Here’s why you should take out a membership of The WM Review today:

Help us continue building the case for a restrained, theological approach to the crisis in the Church

Support an eclectic and sometimes eccentric variety of content

Provide FREE membership to clergy/seminarians (subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

A small monthly membership really helps us keep The WM Review going. Can you chip in today?