Did Lefebvre see the Conciliar Church as a separate society to the Catholic Church?

Are we dealing with a 'sickness' or a 'tendency'—or something more concrete?

Are we dealing with a 'sickness' or a 'tendency'—or something more concrete?

Editor’s Notes

This is part of an essay by John Lane, edited and expanded, with permission, by S.D. Wright.

Whatever one may think about Archbishop Lefebvre, his thoughts, words, and deeds, it is clear that he was an enormously significant figure in the twentieth century response to Vatican II.

Hence, while he is not an authority, what he thought about the Conciliar Church is an interesting and important topic in its own right.

Use of terms

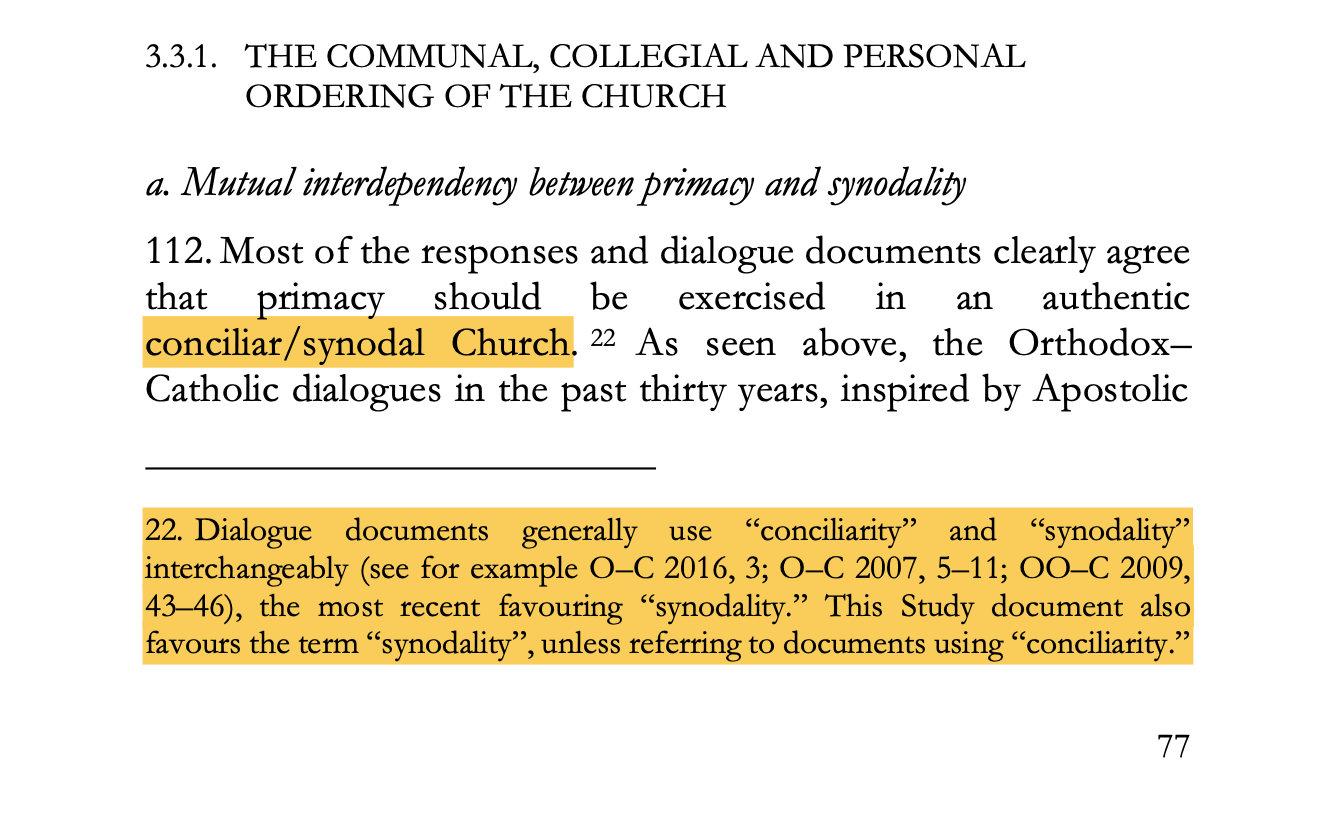

In Decmber 2023, following the Synod on Synodality, we began using the updated term “Conciliar-Synodal Church” to refer to the latest incarnation of the conciliar church of Vatican II. In the 2024 document The Bishop of Rome, published by the Dicastery of Promoting Christian Unity, Cardinal Koch used this term, raising an amusing question: Had he and others in the Vatican been reading The WM Review?

In any case, we are happy to adopt their chosen designation of Conciliar/Synodal in place of Conciliar-Synodal.

Archbishop Lefebvre and the Conciliar Church

By John Lane

Edited and expanded with permission by S.D. Wright

Originally published on the St Robert Bellarmine Forums as a printable PDF here.

Recapitulation

In the previous part, we surveyed the words of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre on what some, including himself, called the “Conciliar Church.” His significance to the twentieth century response to Vatican II makes his views on this subject – and their implications – an interesting subject for consideration. Further, at a time in which more and more are turning to the SSPX as a refuge from the latest restrictions on the Traditional Mass, it is important that we understand what he stood for, and the differences between his work and that of the so-called indult communities.

In this piece, we continue by considering his views on the nature of this Conciliar Church. We will see how different these views are to what many may expect.

We saw that Archbishop Lefebvre frequently spoke of this Conciliar Church as if it was an alternative body of men, operating as a sort of anti-Church. Of all of the texts we gave there, perhaps this sums up his attitude most succinctly:

“We are suspended a divinis by the Conciliar Church and for the Conciliar Church, to which we have no wish to belong. That Conciliar Church is a schismatic Church, because it breaks with the Catholic Church that has always been. It has its new dogmas, its new priesthood, its new institutions, its new worship, all already condemned by the Church in many a document, official and definitive. [...]

“The Church that affirms such errors is at once schismatic and heretical. This Conciliar Church is, therefore, not Catholic. To whatever extent Pope, Bishops, priests, or faithful adhere to this new Church, they separate themselves from the Catholic Church.”1

We ended the first part by asking the following question: What did he have in mind when he used the term “Conciliar Church”? Was it a real entity, consisting of actual members who themselves were its component parts, or merely a kind of metaphor which would assist in explaining the crisis?

How these questions have been answered

Fr. Michael Simoulin, who was District Superior for the SSPX in Italy, gave one set of answers to these questions in the Communicantes publication in 2001:

Indeed, for years now we have become accustomed to speak of the eternal Rome and the modernist Rome, the Catholic Church and the conciliar Church, the Catholic religion and the religion of Assisi, etc… two Romes, two churches, two religions which oppose and confront one another, having apparently nothing in common.

These comparisons are excellent. They strongly depict the drama existing in the Church for the past forty years. They are indicative and accurate, but within the limitations of an analogy. If one accentuates the strict sense of the terms, they may become a source of terrible confusion and may breed a Manicheism (or over-simplification) in which the understanding of the Church, faith in the divinity and a simple sense of the supernatural would be the first victims.

Certainly it is evident that neither Rome nor the Church are made up of material substances or of henchmen, but they are societies, moral entities in which the unity consists of a unity in faith, in hope, and in charity, with a common intention and a will committed to the same goal: the reign of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the salvation of souls, for the glory of God.

Thus, we cannot consider here two entities which are perfectly distinct, unconformable and identifiable, but rather a single moral existence, the sole authentic Catholic Church, but poisoned by a foreign spirit which tends to corrupt and destroy it.

In fact, neither modernist Rome nor the conciliar Church exists distinctly and separately from eternal Rome and the Catholic Church. They cannot, just as the evil cannot exist without leaving its grip on the good which it would like to destroy, and it cannot destroy it without destroying itself.

In reality, what is the conciliar Church? It is precisely the disfigurement of the Catholic Church by the Council and by that which is foreign to its spirit from the interpretation of the Council. Under that which we call the conciliar Church, there still lives the Catholic Church, our mother, buried, sleeping and more or less reduced to silence.”2 [Our emphases.]

On the face of it, this answer appears plausible. But is it what the Archbishop meant when he employed the terms to which Fr. Simoulin refers?

Definition of a society

To answer this question, it will be necessary first to enquire what exactly constitutes a social body, a society. It is evident that Fr. Simoulin is applying the principles found in standard manuals of ecclesiology in order to reach his conclusion. We shall do the same.

In his work The Church of Christ, Fr Berry gives the following detailed definition:

A society may be defined as a union of intelligent beings, entered into for the purpose of attaining a common good by united efforts. A number of individuals is the material element necessary for the formation of a society, but they do not form a society unless banded together for the attainment of a common end by united efforts. Hence the union of wills toward a common end is the formal element of every society. The specific nature of a society may be literary, political, or religious, according to the end to be attained, and the organization of the society will vary accordingly. Hence the end to be attained may be called the external formal element.

The end to be obtained by a society must be more or less permanent. A number of men uniting their efforts to extinguish a fire in a neighbour’s house would not constitute a society. The fact that the purpose of a society is to be attained by the united efforts of all its members, does not mean that each and every member must contribute the same kind of effort or perform the same duties. In this respect a society resembles a physical body in which there are many members, each with its own peculiar function, yet all contribute to the well-being of the whole body, which in turn redounds to the good of each member.

Finally, no purpose can be accomplished unless suitable means are used and properly directed. To this end authority is necessary to coordinate and direct the members in the use of these means. Without authority there can be nothing but confusion and discord, and the society itself would soon perish. Those who exercise authority in a society are its superiors or officials; those subject to this directing or ruling authority are inferiors or subjects.

Practically speaking, authority is the formal element of every society since it is authority that preserves and strengthens all the bonds by which the members are held together.

From the above considerations we deduce the following conditions necessary for a society:

a number of individuals;

a moral union, i.e., a union of wills;

a common end to be attained;

suitable means to attain that end; and

adequate authority.

These five conditions are essential and sufficient to constitute a society. If they are found realized in the Church founded by our Lord, then that Church is a true society.3

The Church founded by Our Lord Jesus Christ certainly meets each and every one of these conditions, and is therefore a true society.

But does the Conciliar Church meet all of these conditions as well? If it did, then it too would be a Society, by definition.

Is that what it is, a real society? Is it a concrete thing, really existing? Or is it merely an ens ratio, a being of reason, a useful metaphor, as Fr. Simoulin asserts?

We will take each of the conditions enunciated by Fr. Berry and see how they are verified in the Conciliar Church, as understood by Archbishop Lefebvre.

Fr Sylvester Berry’s account of a society applied to the “Conciliar Church”

A number of individuals

The first question that must be addressed is whether the Archbishop judged that some men had not merely adopted errors, but had actually left the Church. There can be no doubt of his view. The following is from a press conference in 1983.

Question: How do you see the Church in France at this moment?

Archbishop Lefebvre: I think a good number of bishops are no longer Catholic.”4

He continued, in the same press conference:

“We are in the state England was in at the moment it passed over to Protestantism. One fine day England woke up to find itself Protestant and Anglican. All the bishops, priests and people went over to Anglicanism, and they thought they were doing the right thing. Well, with the Church in France, it's the same thing. It is in the process of passing over to Modernism, worse than Anglicanism.”5

He expressed the sentiment about the French bishops in an interview in 1986.

“The great majority of the bishops in France are apostate, and have abandoned the Catholic Faith to become Modernist. Their new catechism is evident proof of this.”6

In the same interview, Archbishop Lefebvre contrasted these apostates with two other classes of men who, in his estimation, remained in the Church.

“[T]here is in France, an extraordinary resistance on the part of many priests, the faithful, and very many young Catholics. This is a great hope. The Catholic Church survives and is organizing itself against the persecution of the Conciliar Revolution. […]

“Many other bishops among those nominated before Vatican II are with us in their heart, but they do not dare to express this publicly.”7

Finally, on this point, are his now-famous words regarding the new Rome which has eclipsed the Roman Church.

“For the moment they [those in Rome] are in rupture with their predecessors. This is impossible. They are no longer in the Catholic Church. [...]

“Rome has lost the Faith, my dear friends. Rome is in apostasy. These are not words in the air. It is the truth. Rome is in apostasy… They have left the Church… This is sure, sure, sure.”8

So, there certainly exist a number of individuals who have left the Catholic Church in order to cleave formally to the new religion. However, it will have been noticed by attentive readers that Archbishop Lefebvre often qualified his expressions so as to avoid making any blanket judgements of all who did not explicitly reject Vatican II. His sense of justice was too strong for such a view. He was careful to express, in relative terms, the formal principle of the apostasy of our era - which is adherence to the new religion. For example:

“To whatever extent pope, bishops, priests or faithful adhere to this new Church, they separate themselves from the Catholic Church.”9 (Our emphases)

Obviously there exist doubtful cases, such as those in which a given bishop or other individual is materially in error, but is not clearly pertinacious. The Archbishop certainly doubted whether Paul VI or John Paul II formally adhered to the new religion, or were merely confused.

However, doubtful cases are irrelevant to the reality that many of the bishops and faithful have apostatised and are no longer members of the Church. Some men have definitely departed into heresy and they have done so by adhering to the programme of Vatican II despite awareness of the fact that it is incompatible with the teaching of the Catholic Church. There are even a number of cases in which the culprits are on record as asserting that the new doctrines contradict what the Church taught prior to Vatican II, and yet they believed in the novelties anyway.

A moral union, i.e., a union of wills

This condition is also verified in the body of men under discussion. If there is one point upon which Archbishop Lefebvre insisted above all others, it was that it is impossible to give an unqualified adhesion to the texts of Vatican II. And he was equally firm in his denunciations of those who firmly cleaved to those texts and showed by their actions that they were determined to implement them despite all their effects, and in the face of every obstacle.

The Conciliar Church - in the narrow sense defined - is bound together by a union of wills to a definite end, namely the accomplishment of the programme of Vatican II, which is its external formal element, or principle.

A common end to be attained

This end is defined in the documents of Vatican II and is evident in the practical application of that programme. It is essentially man-centred, and seeks the “salvation” of man by the realisation of the divine which is immanent in him. The essential doctrinal content of Vatican II can be summarised in religious liberty, collegiality, and ecumenism, and these correspond with the liberty, equality, and fraternity of the French Revolution. Archbishop Lefebvre was as clear about this as he was about the wilfulness of those who prosecuted the revolution in the Church.

Suitable means to attain that end

The reforms of Vatican II include new laws, new worship, new doctrinal formulations, new structures of authority, and in fact an entire new culture – a kind of pop religion, with appropriate “hymns”, music, moral priorities, approved behaviour, dress standards, language, etc. The new culture, including its worship, laws, and mode of authority, is democratic, anti-hierarchical, popular, coarse, casual, and non-prescriptive. By these means the doctrinal complex of Vatican II, which constitutes the end to be attained, is effectively inculcated in its victims, and excludes Tradition from their souls. All of this was described and condemned by Archbishop Lefebvre, and most especially by his total refusal to admit any of these elements into the practice of religion in his seminaries, priories and chapels.

Adequate authority

Authority is the very banner of the Vatican II revolution in the Church. The employment of this authority is something of a paradox amongst men who disclaim all true hierarchy, however it is certainly real. This is evident in the approach they have taken to traditional Catholics, including the ruthless imposition of the Novus Ordo Missae against all priestly and lay protest, the suspension a divinis of Archbishop Lefebvre and those ordained by him, the excommunications of the Archbishop, Bishop de Castro Mayer, and the four new bishops in 1988, and the general intolerance of any opposition to the key doctrines of Vatican II. One may express doubts about the Resurrection of Our Lord and incur no sanction in the Conciliar Church, but faithful Catholics are persecuted. One of the central themes of Archbishop Lefebvre’s response to the crisis was the distinction between true and false obedience, which presupposes an authority imposing precepts.

As Fr Berry said:

"These five conditions are essential and sufficient to constitute a society. If they are found realised in the Church founded by our Lord, then that Church is a true society."10

Mutatis mutandis, if they are found realised in another body of men, then that body is a true society as well. But we have shown that, at least as Archbishop Lefebvre describes it, they are found in the body of men he denotes as the Conciliar Church. Therefore, on the basis of this analysis, the conclusion is established: this Conciliar Church is a true society in its own right.

Conclusion

There is indeed a society of men conforming to the definition of a society. The Conciliar Church is, by this definition, a real, existing society of men, with a separate existence to the Catholic Church, and this was recognised as such by Archbishop Lefebvre.

It is interesting in its own right to see that this represents the Archbishop's thought, whatever various parties may say about other conclusions or applications he derived from this.

In the next part we shall further establish that this was the Archbishop's mind by considering some addresses from his final years on the four marks of the Church. One of these texts, originally published in Fideliter, has been translated into English by the WM Review, and is very hard to verify and to find in full, whether in the original French or in English. Needless to say, we verified it before publication.

As has been discussed on this website at length, the four marks are the principal means by which the true Church of Christ is identified as such from amongst the various claimants. They are also the principal means by which the Church is rendered visible. As such, a body of men which lacks even one of these four marks or notes – in the sense described by the theologians – thereby shows itself not to be the Church of Christ, but rather another body. Those wishing to read further about this can consult the following essays:

Having considered where, in the Archbishop’s opinion, these four Marks are and are not manifested today, we shall address this thorny question of membership and the status of those who are associated with this Conciliar Church. He certainly stated that membership of the Conciliar Church excluded membership of the Catholic Church. But let us again read carefully the words we have already quoted:

“To whatever extent pope, bishops, priests or faithful adhere to this new Church, they separate themselves from the Catholic Church.”11 (Our emphases)

We have already noted that there is a conditionality in this text. In other words, the "Conciliar Church" as a real existing society does not necessarily denote all those people associated with it or entangled in its structures. According to his words, membership of this Conciliar Church—established, say, by visible adherence to it and its distinctive programme—is indeed exclusive of membership of the Catholic Church.

But, in his words, it does not logically follow from this that every person associated with the Conciliar Church, or every person who thinks and acts as if they are a member of "the official Church," is thereby a member of the Conciliar Church, to the exclusion of being a member of the Catholic Church. It is far from clear that all such persons can be presumed to adhere to the incompatible programme of the Conciliar Church, merely by being entangled in its "visible structures."

We shall address these points in the next part.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further reading:

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Archbishop Lefebvre, Reflections on Suspension a divinis, June 29, 1976. Emphasis added. This text is now difficult to find in English from an SSPX source – nonetheless, here it is in French: https://web.archive.org/web/20211218101234/http://laportelatine.org/formation/crise-eglise/rapports-rome-fsspx/reflexions-de-mgr-lefebvre-a-propos-de-la-suspens-a-divinis-le-29-juillet-1976 and https://laportelatine.org/formation/crise-eglise/rapports-rome-fsspx/reflexions-de-mgr-lefebvre-a-propos-de-la-suspens-a-divinis-le-29-juillet-1976

In this crisis of the Church, let us remain truly ROMAN Catholics, by Father Michel Simoulin, District Superior of the Society of Saint Pius X for Italy, Communicantes, May 2001. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20211220230400/http://fsspx.com/Communicantes/May2001/Let_us_remain_truly_ROMAN_Catholics.htm

Rev. E. Sylvester Berry, D.D., The Church of Christ, An Apologetic and Dogmatic Treatise. Herder, St. Louis and London, 1927 & 1941, pp. 14-16.

Press Conference, Paris, 9 December 1983. Availabel at: https://web.archive.org/web/20211220230747/http://www.sspxasia.com/Documents/Archbishop-Lefebvre/Press-Conference.htm

Ibid.

Interview with Don McLean, Editor of Catholic, January 1986. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20211220231215/http://www.sspxasia.com/Documents/Archbishop-Lefebvre/Interview_With_Archbishop_Lefebvre_Jan_86.htm

Ibid.

Retreat Conference, September 4, 1987, Econe. This can be difficult to find in English from official sources, but it is available here in French: https://web.archive.org/web/20211220232047/https://laportelatine.org/actualite/les-odeurs-de-rome-occupee-editorial-du-sel-de-la-terre-n-87-de-lhiver-2013-2014

Archbishop Lefebvre, Reflections on Suspension a divinis, June 29, 1976. Emphasis added. Link above.

Berry 16.

Archbishop Lefebvre, Reflections on Suspension a divinis, June 29, 1976. Emphasis added. Link above.