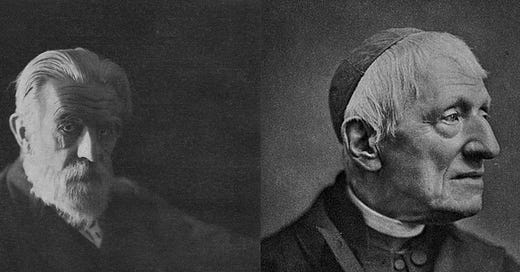

Was Cardinal Newman 'very friendly' with 'arch-modernist' Baron von Hügel?

Some have tried to cast Cardinal John Henry Newman as 'guilty by association' with Baron von Hügel—but what is the evidence for their supposedly close friendship?

This is Part III. See Part I here and Part II here.

This is an addendum to the previous pieces answering certain criticisms made of Cardinal John Henry Newman. It was originally a response to a video made in November 2022, in which Newman was accused of having ‘remained a Protestant down deep’ and of holding modernist principles and ideas about conscience.

I have demonstrated the injustice of these accusations here and here. Having addressed the main points made in this video, and having called for its creators to remove it and retract its claims, this piece will address its innuendo about Newman being ‘very friendly’ with Baron Friedrich von Hügel.

Baron Von Hügel

The accusation ran as follows:

‘And he was very friendly with von Hügel, [disgusted face] who was a German (sic) living in England, who was an arch-modernist, the devil himself, practically, as regard to modernism.

‘And Newman always just stayed on this side of the demilitarised zone, so to speak, [Interviewer laughing] in order to avoid the accusation of modernism.

‘But his principles are modernist. That idea of conscience is precisely modernist.’

As mentioned, I have already shown the falsity of the final statement – that Newman’s ideas of conscience were ‘precisely modernist’. His ideas were, in fact, the same as the creator of the video.

Let’s also note that the creator of this video has made a similar claim about von Hügel and Newman before, in an article on his blog. While this claim did there enjoy the presence of a footnote, the footnote provided no evidence of such association or even mention of von Hügel. Instead, it merely consisted of an extract from one of Newman’s Anglican works, which the author called ‘thoroughly modernist’ and comparable to ‘the arch-modernist excommunicate Alfred Loisy.’1

Needless to say, this is irrelevant, and does not prove anything about Newman as a Catholic – nor that he was ‘very friendly’ with von Hügel.

That which is asserted without evidence, falls with a simple denial.

I deny 1) that Newman was ‘very friendly’ with von Hügel in the sense implied by such accusations, and 2) that, even if he was ‘very friendly’ with him, such a relationship would in itself taint Newman by association, in the way that the innuendo implies.

Those who wish to make such attacks on the reputation of others – especially those who cannot defend themselves – should provide evidence, which can then be discussed.

In the meantime, here are the facts.

Von Hügel was a prominent Austrian (not German) aristocrat. His was a prominent family, as was that of his wife. It may be difficult for us today, in a more egalitarian society, to understand the real importance and influence that certain aristocratic families had, and the corresponding moral duties which clergymen might hold towards them.

Von Hügel’s mother-in-law was a very well-connected Catholic convert, and the baron’s biographer states that Newman and Vaughan thought that the marriage was a good match.2 But even on religious grounds (to say nothing of natural) this is entirely understandable: when they married in his early twenties, before a lifetime of intellectual work revealing the way his mind turned, von Hügel was considered to be a thoughtful and externally pious young man.3

On the subject of age: von Hügel was 51 years Newman’s junior. This is an unusual (though not impossible) age difference to exist between those who were ‘very friendly’ in the sense implied.

Letters exchanged

It is true that Newman exchanged letters with von Hügel – as both men did with very many others, and as was much more common at the time than it is today. Drawing conclusions about who was ‘very friendly’ with whom based on letter-writing, might be akin to drawing the same conclusions based on email correspondence today. We all know that this would be foolish.

These letters – as with all Newman’s letters – could perhaps be described as being ‘very friendly’, in that they were written properly, and were respectful, polite and occasionally warm. Those who are not used to writing in proper form might draw unwarranted conclusions from this. But it should be clear that interacting with someone in a way governed by basic manners and warmth is not the same as being ‘very friendly’ in the sense insinuated.

In fact, reading between the lines of some of Newman’s surviving correspondence, it seems that he was trying to help von Hügel stay ‘in the light’, so to speak.4

Further, von Hügel himself was also less than flattering about Newman on several occasions, as can be seen in his biography by de la Bedoyere:

‘One would have expected that in these early years the influence of the great cardinal, standing as he did so high above his Catholic and Christian contemporaries, so original and generous in his spiritual perceptions, and, after all, personally known both to the baron and to his wife, would have been paramount.

‘If so, there is no evidence of the fact, and it is certainly clear that any strong influence felt at the time did not endure.

‘There are surprisingly few references to Newman in the baron’s writings, and these few usually sound a critical note. “I used to wonder, in my intercourse with John Henry Newman, how one so good, and who had made so many sacrifices to God, could be so depressing”, he wrote in 1921.’5

(Let’s note that we are not treating this biography as an impartial or reliable account – but one would have thought that if there were any serious grounds for portraying the relationship with Newman as ‘very friendly’, then de la Bedoyere’s agenda would have prompted him to do so.)

Further, in his famous collection of letters to his niece, von Hügel said the following of Newman’s Parochial and Plain Sermons:

‘But then these sermons are rigorist – how they have depressed me!’6

So much for a ‘very friendly’ relationship based on a shared religious outlook.

Von Hügel’s other associations

Von Hügel also wrote widely and carried out correspondence with all sorts of persons, including W.G. Ward and Evelyn Waugh. De la Bedoyere suggests that his interactions with Ward were considerably warmer than those with Newman.7

Consider also the apparent honours given in relation to Cardinal Manning:

‘Grander ecclesiastical contacts occurred when Cardinal Manning reopened the parish church on 5th May 1877, and the baron sat next to him at the subsequent luncheon, thus seemingly considered already the most notable parishioner.’8

He also met with Pius XI and Pius XII before they were popes, enjoying walks with the latter – and with the former even helping him with aspects of his research and writing.9

Would we want to insinuate something about these men too?

Of course not. Von Hügel’s biographer gives family prominence as a much more common-sense explanation for his standing, in relation to Dr Vaughan (who was later Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster), Bishop Hedley and Newman himself:

‘Breakfast with Dr. Vaughan, then Bishop of Salford, is explained by his mother-in-law’s friendship with the future cardinal. What with this, correspondence with Newman, and intimacy with Dr. Hedley, who stayed with them, it is evident that the baron and Lady Mary, combining blood with piety, took their place naturally in the highest Catholic Church society.’10

Should Newman have shunned von Hügel?

First, we should ask whether Newman can be negatively judged for not doing something that men like Cardinal Mercier, Hedley, Ratti, Pacelli, Manning, Ward and Vaughan also did not do – at least, without this negative judgment rebounding on to them. We are left wondering, again, why Newman is criticised for that which is passed over or praised in others.

But in any case, it would be wrong to suggest that friendship or friendly associations with a liberal, modernist or a sceptic automatically taints a man by association.

As is clear from his life, writing and correspondence, Newman was animated by a love for souls and a desire to help everyone become and remain a Catholic. In this case, as I have already mentioned, some of Newman’s letters suggest that he (like Cardinal Pacelli and others) were trying to help this prominent and influential layman stay within the bounds of orthodoxy.

Further, neither Newman, nor indeed most people, believe that the best way of achieving this is by privately deciding to shun everyone who is teetering on the edge, or who has already fallen – even if this can indeed be necessary at times.

As Our Lord said:

‘For the Son of man is come to save that which was lost. What think you? If a man have an hundred sheep, and one of them should go astray: doth he not leave the ninety-nine in the mountains, and goeth to seek that which is gone astray? And if it so be that he find it: Amen I say to you, he rejoiceth more for that, than for the ninety-nine that went not astray. Even so it is not the will of your Father, who is in heaven, that one of these little ones should perish.’ (Matt. 18.11-14.)

While one may eventually need to treat one who ‘will not hear the Church’ as ‘the heathen and the publican’, the facts of this case make it seem a very unworthy basis of condemning Newman.

Conclusion to all pieces

To summarise, there is little evidence in Newman’s correspondence for suggesting that Newman was ‘very friendly’ with von Hügel. There is still less in de la Bedoyere’s biography, which is precisely where we would expect to find such evidence, if it existed.

But this matter of von Hügel is, as I mentioned, a mere addendum to the more substantial accusations, against which I have already presented a defence here and here.

Those accusations are unjust falsehoods. The burden of proof for all such claims about Newman – both those which refer to von Hügel, and any other outrageous comments – lies on the shoulders of those making them.

For these reasons, it is important for those who make such accusations not to retreat into what St Pius X called a ‘conspiracy of silence’, but to give an answer for them when challenged. They should either prove their claims, and refute the defences offered – or they should retract them, and make restitution for the unjust assault on Newman’s reputation.

Read Next:

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

‘Suspended magisterium?’, on In Veritate, March 26 2019. Accessed 29 Nov 2023 from https://inveritateblog.com/2019/03/26/suspended-magisterium/

Michael De la Bedoyere, The Life of Baron von Hügel, p 8. J.M. Dent, London, 1951.

Cf. the practice followed in his early married life, in the late 1870s:

‘Mass and communion twice a week (a regular habit maintained when health would allow through life) and confession often more than once a week, together with frequent visits to the Blessed Sacrament, were the outward religious routine.’ Ibid. 23-4

Cf. the letters in ibid., 29-31

Ibid. 32.

Letters from Baron Friedrich von Hügel to a Niece, ed. Gwendolen Greene, p 116. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, London.

Cf. de la Bedoyere pp 23-37

Ibid. 24

For instance de la Bedoyere writes:

‘… most interesting of all perhaps to-day, Don Eugenio Pacelli with whom the baron had constant walks and who at the time was most forthcoming in regard to the biblical and other questions interesting von Hügel.’ 88

‘In Rome that spring the baron, who had resumed his bicycling and who was frequently meeting two future popes, Don Ratti and Don Pacelli, also often saw a personage destined soon to become much more important, the half English Mgr. Merry del Val, with whom, as with Cardinal Vaughan, he was then persona grata because of family connections.’ 125

‘At the Ambrosiana he was helped in his research by ‘Scrittore Ratti,’ the future Pius XI…’ 130

Regarding the censorship and surveillance of a particular journal, de la Bedoyere even tries portray a certain intimacy and confidence with the future Pius XI:

‘A very strange fate brought him at this moment into discussion of the whole position with Don Achille Ratti -the future Pius XI – in the Ambrosian Library. In his Diary for the 12th December 1907, he notes: ‘Saw Don Achille ratti: he talks to me about “Rinn.” in characteristically scholastic, traditional way, tho’ with kindly feeling fo the young men.”

‘Don Ratti was in fact in close relations with Scotti, a disciple of his, and was most anxious to see the matter settled. He proposed to the baron a settlement along the lines of an apology for the way the Review had criticized Pascendi, in return for which it would be allowed to continue under the surveillance of a broad-minded censor, like the Dominican Genocchi […]’ 206-7.

Ibid. 24