Is Cardinal Newman's idea of conscience 'precisely modernist,' as Bishop Sanborn claims?

Bishop Donald Sanborn has alleged that '[Newman’s] idea of conscience is precisely modernist’ – but Newman's idea was identical to that of his accuser and of St Thomas Aquinas.

Introduction: Reflections on the controversy

In November 2023, Bishop Donald Sanborn – Rector of Most Holy Trinity Seminary and Superior General of the Roman Catholic Institute – published a video reacing to an interview between Bishop Robert Barron and Ben Shapiro.1

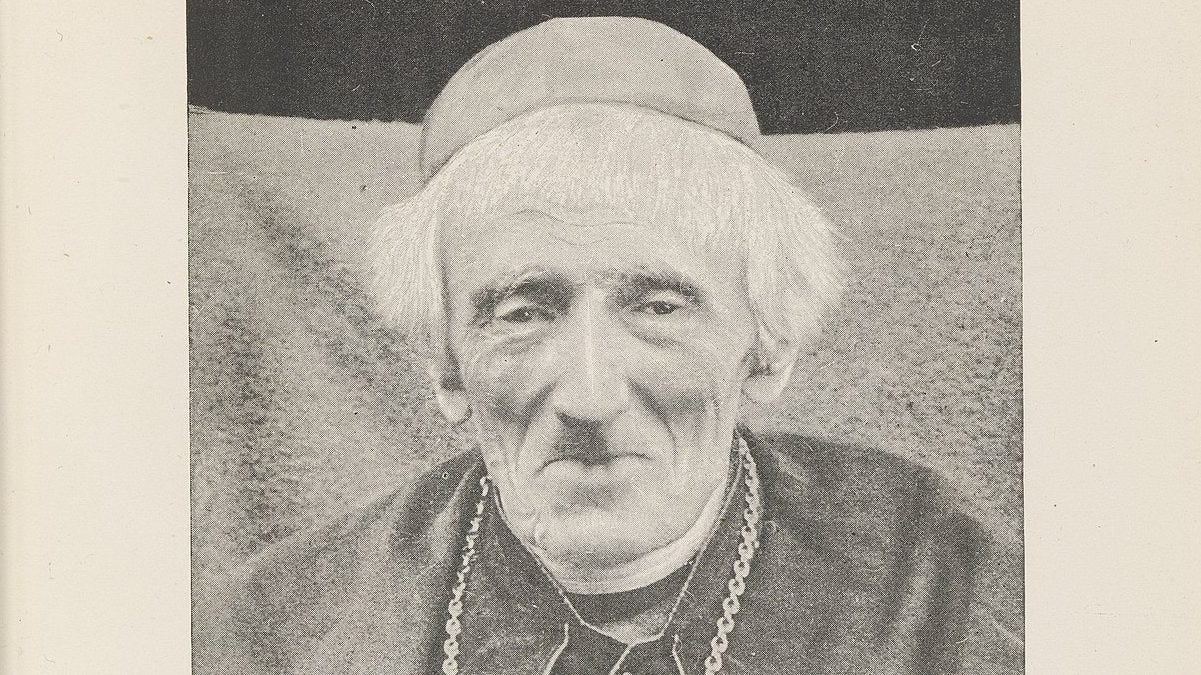

This video featured remarks about Cardinal John Henry Newman which can only be described as gravely calumnious.

In response, we published a three-part refutation of Bishop Sanborn’s claims, calling for the video to be removed, and for reparation to be made to Newman’s good name.

A few months later, in March 2024, the Bishop was asked about these articles in a livestream video. While there was still much to which we objected in his response to the question, we noted Bishop Sanborn’s significantly moderated tone, and took this as the closest that he might come to a retraction. We subsequently redacted the three articles, removing references to the Bishop’s name – preferring to avoid being in open conflict with the Bishop.

However, we are surprised and disappointed to say that in August 2025, Bishop Sanborn has renewed the same calumnies, in almost the same words, in another video and his seminary newsletter. This renewal was prompted by Leo XIV announcing, in August 2025, that Newman would be named a Doctor of the Church.

We share Bishop Sanborn’s dismay at this, for some of the same reasons. As my colleague Matthew McCusker in an interview with Kokx News:

“My initial reaction was one of dismay, because the enemies of the Church will certainly use this recent declaration to promote Modernism and Liberalism. They will do this by misrepresenting Newman as a liberal and proto-Modernist, even though his entire life was dedicated to the destruction of Liberalism and though he foresaw the coming of Modernism and sounded the alarm.”

Novus Ordo Watch reached a similar judgment, and issued the following exhortation:

“Traditional Catholics should not allow the (Neo-)Modernists to claim Newman as one of their own, for he most certainly wasn’t. […]

“Let’s not let the Vatican II religionists claim John Henry Newman as one of their own by distorting his teachings, by canonizing him, or by declaring him a Doctor of the Church.”

But just as we will not allow the Conciliar/Synodalists or semi-Catholics to claim Newman unchallenged, neither will we remain silent while others condemn Newman unjustly.

For this reason, we are republishing an updated and unredacted analysis of Bishop Sanborn’s criticisms of this great man, and prince of the Holy Roman Church.

Bishop and Cardinal Mini-Series

Part I: Is Cardinal Newman’s idea of conscience ‘precisely modernist,’ as Bishop Sanborn claims?

Part IIa: Bishop Sanborn, and Cardinal Newman’s ‘Proof from Conscience’

Part III: Bishop Sanborn’s attempt to link Cardinal Newman with Baron von Hügel

The 2023 exchange in full

Let us remind ourselves of how the Bishop’s exchange with Stephen Heiner unfolded. Following a clip of Barron’s attempt to marshal Newman in favour of his liberal ideas, Heiner and the Bishop reacted as follows:

Stephen Heiner: [Laughing] “So, I know you never want to miss an opportunity to talk about your challenges with Cardinal Newman, your Excellency. Why don’t we start there?”

Bishop Sanborn: [Laughing] “Well first of all, let me explain conscience. What conscience is, and what it is not.”

Stephen Heiner: [Laughing] “OK.”

Bishop Sanborn: “What conscience is, is simply your intellect applying the law to something that you are about to do, or have done. The law that – the moral law. That’s all it is. It’s not some special faculty in your brain or in your intellect or something like that where you get signals from heaven. Some sort of telephone to Heaven about what’s true and what’s false. It is simply – it concerns morality, and it is simply the application of the law as you know it.

“So, you could have an erroneous conscience: that is, that you have been misinformed about what the law is – the moral law, or whatever it is – and you could decide that something is good which is in fact evil. That’s possible, and you could be in what we call “good conscience,” because you don't know any better. That’s possible. But good conscience does not justify, it only excuses.

“So to… you know, he [Bishop Robert Barron] is giving this idea of conscience as exactly what Newman says, it’s the Vicar of Christ in your soul.

“Well that is, that means, why do we need a pope if have the vicar of Christ in souls? Why do we need a church? This is pure Protestantism. This is free examination of the scriptures – the Holy Ghost comes and tells me what I should think. Well, why do we have a Church? Why did St Peter receive the keys? Why is there the magisterium of the Church?

“And as I said, conscience only regards the moral law, it does not regard the truths of the faith or anything like that. The faith is something objective, it is taught by the Church, you have to discover it.

“But conscience – You know with Newman, the famous story of Newman? They toasted the pope – he was with some people, and they, there was someone offered a toast to the pope, and he said – ‘Yes – but to conscience first.’”

Stephen Heiner: [Laughing] “And you were very bothered by that.”

Bishop Sanborn: [Laughing, then disgusted] “Urgh, that made me sick, and it, just shows that his conversion was more of a dragging the Church to himself, rather than dragging himself to the Church.

“He loved Catholicism so he thought he would buy it and have it in his garage. He remained a Protestant down deep, but he acquired some Catholicism. That’s my opinion of Newman.”

Stephen Heiner: [Laughing] “I was going to say this, triggering the next Questions for the Rector episode, your Excellency, you’ll see, as some faithful clutch their pearls in shock.’

Bishop Sanborn: [Laughing] “I have a very low opinion of Cardinal Newman – very, very low.”

“And he was very friendly with von Hügel, [disgusted face] who was a German (sic) living in England, who was an arch-modernist, the devil himself, practically, as regards to modernism.

“And Newman always just stayed on this side of the demilitarised zone, so to speak, [Interviewer laughing] in order to avoid the accusation of modernism.

“But his principles are modernist. That idea of conscience is precisely modernist.’

Stephen Heiner: “But it ties in, that’s why Bishop Barron likes it so much.”[Laughing]

Bishop Sanborn: “Oh yes, you know, you have the phone to God. You have the internet connection to Heaven.” [Both laughing]

These comments were variously false or unfair, and demonstrated a grave misunderstanding both of what Newman actually said, and the context in which it was written.

We do not fault Bishop Sanborn for a lack of knowledge about Cardinal Newman: no-one is obliged to be knowledgeable about such a subject. However this is the case unless and until someone begins speaking out of this ignorance in a way that is unjust – and persisting in this injustice even after having been notified of it.

Bishop Sanborn may suggest, as he did in March 2024, that this controversy is “a sideshow,” and that he does not see “why we have to have a war about Cardinal Newman.”2 Indeed, we do not “have to have a war about Cardinal Newman” – but in fact, it was the Bishop himself that chose to condemn Newman in such a sweeping fashion. If the subject is unimportant, then why speak in such a way?

Further, the truth and justice matter, and even the dead have a right to their good name, and it is hardly a “war” for us to vindicate the good name of a deceased Cardinal who can no longer do so himself.

Therefore, out of respect for Cardinal Newman himself, as well as respect for…

Pius IX, who entrusted him with the foundation of the Oratory in England, and who said of him “I do not in the least doubt Father Newman's obedience” and that he was “tutto ubbediente” (“totally obedient”)3

Leo XIII, who appointed him cardinal (and was ‘undoubtedly a shrewd judge of men and affairs’ according to St Pius X when discussing this appointment4

St Pius X himself, who praised Newman, and defended him against the modernists’ cynical co-opting of his name to add prestige to their agenda5

Pius XI and Pius XII, who both publicly praised him6

Many other churchmen, such as Bishop Ullathorne and Cardinal Barnabo and others who took his part in the face of attacks…

… let us proceed with the refutation of Bishop Sanborn’s calumnies against the great man and Prince of the Holy Roman Church.

Letter to the Duke of Norfolk – the witness of Manning and Ward

In the reaction video in question, the bishop referred to two famous comments made in Newman’s 1875 Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, a book defending the papacy against attacks made by the prominent Anglican politician, William Gladstone.

Gladstone had been Prime Minister between 1868 and 1874, and would later serve a further three terms in the years between 1880 and 1894.

Newman’s book was polemical in nature. It was not intended as a treatise of theology, and it has been a source of misunderstanding that some later writers have taken it as such.

The vast majority of Catholics saw it as a successful vindication of the doctrine of papal infallibility in relation to the civil obedience of the Catholic population of the United Kingdom.

Among those who welcomed it were Cardinal Manning and W.G. Ward, who had opposed themselves to Newman for many years. This may be surprising to some: in his biography of Bishop Ullathorne, Dom Cuthbert Butler observes:

“There lingers on still in many minds a vague traditional sense that Manning and Ward were the fully sound Catholics of those days, and that their ideas were proclaimed at the Vatican Council as the Catholic Faith […]”7

W.G. Ward’s son, Wilfrid Ward, recounts his father’s reaction:

“He spoke in the Dublin Review with great cordiality of Newman’s pamphlet, and expressly denied that its positions could be charged with the ‘minimising’ tendency he had denounced. This gave the note for others who belonged to his school of thought, and the pamphlet was welcomed almost without a dissentient voice.”8

Wilfrid Ward also noted that, thanks to this affair, “active opposition between [Newman and Ward] was henceforth at an end.”9

Cardinal Manning defended Newman’s pamphlet in a private letter to Rome. Among his points we find the following:

“The heart of the revered Fr Newman is as right and as Catholic as it is possible to be.”

“His pamphlet exercises a most powerful influence upon the non-Catholics of [England].”

“In like manner, the effect of it on Catholics of an intractable disposition and incorrect ideas is a wholesome one.”10

He notes that “the substance of the recent pamphlet is sound” – and while he said that he was “sensible of certain propositions and of a certain method of reasoning which are wanting in accuracy of expression,” he dismissed this as “slight blemishes” which “are not apparent to non-Catholics, or to Catholics who are of defective instinct” and that “[o]n the more clear-sighted among Catholics they have no influence at all.”11

He concluded his letter:

“I can with all confidence declare that Catholic Truth and the Authority of the Holy See will not in the slightest degree be diminished by the aforesaid pamphlet; and that never to this day did the unity of Catholics and the infallibility of the Vicar of Christ shine forth more brightly in England.”12

Now, we should recall that Bishop Sanborn objected to two particular comments made in Newman’s pamphlet, namely:

The comment, “Conscience is the aboriginal Vicar of Christ” – which Sanborn carelessly paraphrases as “the Vicar of Christ in your soul” and which he loads with a set of modernist assumptions

The rhetorical remark about after-dinner toasts “to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards”13 – which Sanborn misrepresents as having been a real event, whilst also missing the wider social and historical context (which casts the comment in pro-papal light).

Many do not know what to make of these comments, and they are often presented in isolation from the rest of the chapter and of Newman’s work – as the Bishop himself does.

Cardinal Manning and Ward were notoriously exigent in critiquing any deviation from their conception of the Roman prerogatives. It is scarcely credible to think that these men (or others of their party) would have missed these comments or their significance, if Bishop Sanborn’s understanding is correct. It is still less credible – indeed, it is risible – to think that men such as Manning and Ward could have praised the pamphlet in such terms, if the Bishop were correct.

On the contrary, Bishop Sanborn has unfortunately fallen for narrative of the modernists, exposed and rejected by Pope St Pius X in his letter on Newman.

The techniques of the modernists, exposed by Pope St Pius X

Newman’s comments about conscience have indeed been used by modernists – and were indeed being abused in Bishop Barron video to which the Bishop was responding.

However, being co-opted by heretics is not equivalent to being suspect oneself. If it were, we might be forced to conclude that all the men and women canonised or beatified by the post-conciliar papal claimants (such as even Pius IX) were suspect; but we know that many, who died long before Vatican II, were exemplary Catholics.

We might also have to suspect St Augustine, who was recruited by Protestants and Jansenists to justify their heretical positions.

On the contrary, heretics will co-opt whomsoever they like; all things being equal, it is as gratuitous to assume that this reflects badly on Newman as it does on St Augustine.

The co-opting of Newman started a long time ago. In his letter to Bishop O’Dwyer of Limerick, St Pius X rebuked modernists for this, and ordered them to desist:

“It is clear that those people whose errors We have condemned in that Document had decided among themselves to produce something of their own invention with which to seek the commendation of a distinguished person. […]

“Not only do you fully demonstrate their obstinacy but you also show clearly their deceitfulness.

“[W]hat the Modernists do is to falsely and deceitfully take those words out of the whole context of what he meant to say and twist them to suit their own meaning.’”14

Pope St Pius X then chastises the modernists for “being addicted to their own prejudices’, and orders them to desist from “abusing his name and deceiving the ignorant.”15

It would be well for some traditionalist critics of Newman to do the same.

With that in order, let us see how Bishop Sanborn treats Newman on the matter of conscience, and consider Newman’s understanding of conscience in the context of the whole chapter – recalling that it is normal to understand a passage in light of a chapter, rather than the other way around.

What is conscience?

Bishop Sanborn starts his discussion of Newman with a definition of conscience, implying that he is thereby preparing the ground for a critique of the late cardinal’s views. Here is the relevant section of the exchange:

Bishop Sanborn: “What conscience is, is simply your intellect applying the law to something that you are about to do, or have done. The law that – the moral law. That’s all it is. It’s not some special faculty in your brain or in your intellect or something like that where you get signals from heaven. Some sort of telephone to Heaven about what’s true and what’s false. It is simply – it concerns morality, and it is simply the application of the law as you know it.”

However, in the chapter in question, Newman lays out the same doctrine of conscience which Bishop Sanborn accuses him of rejecting:

“I observe that conscience is not a judgment upon any speculative truth, any abstract doctrine, but bears immediately on conduct, on something to be done or not done.

“‘Conscience,’ says St. Thomas, ‘is the practical judgment or dictate of reason, by which we judge what hic et nunc is to be done as being good, or to be avoided as evil.’ Hence conscience cannot come into direct collision with the Church’s or the Pope’s infallibility; which is engaged in general propositions, and in the condemnation of particular and given errors.”16

Now, Bishop Sanborn says of Newman’s views:

“That idea of conscience is precisely modernist.”

Is Bishop Sanborn condemning his own idea of conscience as “precisely modernist”? Of course not.

So is the Bishop condemning Newman as a modernist on quite mistaken grounds? Or is Newman’s citation of St Thomas merely a cover for a “precisely modernist” idea? Let us consult the rest of the chapter to see.

Divine and natural law

At the start of the chapter, Newman states that one cannot deal with the topic of conscience without starting with God, and the divine and natural law.

“… [N]ow I must begin with the Creator and His creature, when I would draw out the prerogatives and the supreme authority of Conscience.

“I say, then, that the Supreme Being is of a certain character, which, expressed in human language, we call ethical. He has the attributes of justice, truth, wisdom, sanctity, benevolence and mercy, as eternal characteristics in His nature, the very Law of His being, identical with Himself; and next, when He became Creator, He implanted this Law, which is Himself, in the intelligence of all His rational creatures.

‘The Divine Law, then, is the rule of ethical truth, the standard of right and wrong, a sovereign, irreversible, absolute authority in the presence of men and Angels.

“‘The eternal law,’ says St. Augustine, ‘is the Divine Reason or Will of God, commanding the observance, forbidding the disturbance, of the natural order of things.’

“‘The natural law,’ says St. Thomas, ‘is an impression of the Divine Light in us, a participation of the eternal law in the rational creature.’”17

He then relates this to conscience:

“This law, as apprehended in the minds of individual men, is called ‘conscience;’ and though it may suffer refraction in passing into the intellectual medium of each, it is not therefore so affected as to lose its character of being the Divine Law, but still has, as such, the prerogative of commanding obedience.

“‘The Divine Law,’ says Cardinal Gousset, ‘is the supreme rule of actions; our thoughts, desires, words, acts, all that man is, is subject to the domain of the law of God; and this law is the rule of our conduct by means of our conscience.’”18

Newman proceeds to consider some faulty views of conscience, held by naturalists and by the various protestant sects, and points out that many of his contemporaries held “a counterfeit” understanding of conscience:

“[L]et us see what is the notion of conscience in this day in the popular mind. There, no more than in the intellectual world, does ‘conscience’ retain the old, true, Catholic meaning of the word. There too the idea, the presence of a Moral Governor is far away from the use of it, frequent and emphatic as that use of it is.

“When men advocate the rights of conscience, they in no sense mean the rights of the Creator, nor the duty to Him, in thought and deed, of the creature; but the right of thinking, speaking, writing, and acting, according to their judgment or their humour, without any thought of God at all.

“They do not even pretend to go by any moral rule, but they demand, what they think is an Englishman’s prerogative, for each to be his own master in all things, and to profess what he pleases, asking no one’s leave, and accounting priest or preacher, speaker or writer, unutterably impertinent, who dares to say a word against his going to perdition, if he like it, in his own way. Conscience has rights because it has duties; but in this age, with a large portion of the public, it is the very right and freedom of conscience to dispense with conscience, to ignore a Lawgiver and Judge, to be independent of unseen obligations.

“It becomes a licence to take up any or no religion, to take up this or that and let it go again, to go to church, to go to chapel, to boast of being above all religions and to be an impartial critic of each of them. Conscience is a stern monitor, but in this century it has been superseded by a counterfeit, which the eighteen centuries prior to it never heard of, and could not have mistaken for it, if they had. It is the right of self-will.”19

Let us note that in this passage, Cardinal Newman also rejects the concept of religious liberty. In fact, elsewhere in the same work, he defends the teaching of Pius IX’s Quanta Cura and Gregory XVI’s Mirari Vos on the matter of liberty of conscience and religion:

“It seems a light epithet for the Pope to use, when he calls such a doctrine of [liberty of] conscience deliramentum: of all conceivable absurdities it is the wildest and most stupid.”20

Thus, Newman’s idea of conscience is correct, and he correctly distinguishes it from other conceptions which are false, and condemns the “absurdities” that arise from these false ideas. It is therefore incorrect to say, as the Bishop does, that “that idea of conscience is precisely modernist.”

In fact, it seems identical to Bishop Sanborn’s own explanation of conscience.

To understand this matter even further, let’s consider the charges levelled by Gladstone, which gave rise to the pamphlet in the first place.

The context of the discussion: Gladstone’s accusations of ‘mental slavery’

As mentioned, the immediate context of the Letter itself was Gladstone’s own pamphlet, which accused English Catholics of being the “mental slaves” of the pope, absolved from independent responsibility, and incapable of being trustworthy subjects of the state.

For instance, Gladstone suggests that the Vatican I definition of infallibility meant that English Catholics would be obliged to obey a papal command to burn down Portsmouth. Newman quotes him:

“[Gladstone] says, p. 35,

“‘It may be sought to plead that the Pope does not propose to invade the country, to seize Woolwich, or burn Portsmouth. He will only, at the worst, excommunicate opponents … Is this a good answer? After all, even in the Middle Ages, it was not by the direct action of fleets and armies of their own that the Popes contended with kings who were refractory; it was mainly by interdicts,’ etc.”21

Newman answers this objection:

“What have excommunication and interdict to do with Infallibility? Was St. Peter infallible on that occasion at Antioch when St. Paul withstood him? was St. Victor infallible when he separated from his communion the Asiatic Churches? or Liberius when in like manner he excommunicated Athanasius?

“And, to come to later times, was Gregory XIII., when he had a medal struck in honour of the Bartholomew massacre? or Paul IV. in his conduct towards Elizabeth? or Sextus V. when he blessed the Armada? or Urban VIII. when he persecuted Galileo? No Catholic ever pretends that these Popes were infallible in these acts.

“Since then infallibility alone could block the exercise of conscience, and the Pope is not infallible in that subject-matter in which conscience is of supreme authority, no deadlock, such as is implied in the objection which I am answering, can take place between conscience and the Pope.”22

(Let’s note that in this section, Newman both explicitly notes that the exercise of infallibility could indeed “block the exercise of conscience”, and shows that he has the same conception of the subject-matter of conscience as Bishop Sanborn, namely, acts here and now, rather than doctrine.)

“Catholics would be obliged to burn down Portsmouth” represents the sorts of argument Newman is addressing with his comments – and he is correct that both Catholic teaching and sound philosophy hold that conscience may prevent a man from obeying such commands.

But we all know this already. We know that the pope’s non-universal commands (as opposed to actual universal ecclesiastical laws and decisions) are not infallibly protected from running counter to conscience in all cases, or even being evil in themselves. This same point is made with admirable clarity by Fr Damien Dutertre, a priest of Bishop Sanborn’s Roman Catholic Institute, in a paper from November 2022:

“The particular commands, and the personal actions of the pope, are not the object of the special assistance promised by Christ to His Church through the divine institution of the papacy. They may sometimes be legitimately resisted and denounced.

“What cannot be resisted, and what is always guaranteed by the assistance of the Holy Ghost are decisions on faith and morals, imposed on the universal Church, as well as universal disciplinary and liturgical laws, such as the promulgation of a new rite of the Mass.”23

Newman rejects self-will and private judgment

Even having made the relevant distinction, Newman warns against rashly concluding that a given papal command, of the kind discussed – which, as Fr Dutertre shows, we all agree would not be infallible – actually contradicts the strictures of conscience, and thus can be resisted or disobeyed:

“… I have to say again, lest I should be misunderstood, that when I speak of Conscience, I mean conscience truly so called.

“When it has the right of opposing the supreme, though not infallible Authority of the Pope, it must be something more than that miserable counterfeit which, as I have said above, now goes by the name. If in a particular case it is to be taken as a sacred and sovereign monitor, its dictate, in order to prevail against the voice of the Pope, must follow upon serious thought, prayer, and all available means of arriving at a right judgment on the matter in question…”24

(Note again that there is nothing to suggest that Newman is talking about rejecting papal teaching or speculative truths, which he has already explicitly excluded from the discussion.)

“And further, obedience to the Pope is what is called ‘in possession;’ that is, the onus probandi of establishing a case against him lies, as in all cases of exception, on the side of conscience. Unless a man is able to say to himself, as in the Presence of God, that he must not, and dare not, act upon the Papal injunction, he is bound to obey it, and would commit a great sin in disobeying it. Primâ facie it is his bounden duty, even from a sentiment of loyalty, to believe the Pope right and to act accordingly.

“He must vanquish that mean, ungenerous, selfish, vulgar spirit of his nature, which, at the very first rumour of a command, places itself in opposition to the Superior who gives it, asks itself whether he is not exceeding his right, and rejoices, in a moral and practical matter to commence with scepticism. He must have no wilful determination to exercise a right of thinking, saying, doing just what he pleases, the question of truth and falsehood, right and wrong, the duty if possible of obedience, the love of speaking as his Head speaks, and of standing in all cases on his Head’s side, being simply discarded. If this necessary rule were observed, collisions between the Pope’s authority and the authority of conscience would be very rare.

“On the other hand, in the fact that, after all, in extraordinary cases, the conscience of each individual is free, we have a safeguard and security, were security necessary (which is a most gratuitous supposition), that no Pope ever will be able, as the objection supposes, to create a false conscience for his own ends.”25

Newman then gives a set of Catholic authorities proving, against Gladstone, that Catholics believe that conscience must be obeyed against any sinful command from authority. This is a long section in the chapter, with Newman citing Cardinal Gousset, the Salmanticenses, as well as “St. Thomas, St. Bonaventura, Caietan, Vasquez, Durandus, Navarrus, Corduba, Layman, Escobar, and fourteen others” – “two of whom,” he says, “even say this opinion is de fide.”26

He cites one Cardinal Jacobatius making clear that, if it were necessary, this teaching would also apply to any sinful commands (as opposed to a universal disciplinary laws) that may hypothetically come from the Roman Pontiff.27

But there should be no need to prove this point, which we all know is true, and which (given the text from Fr Dutertre) Bishop Sanborn would surely concede.

Preliminary Conclusions

So far, we have considered whether Bishop Sanborn accurately and fairly portrays Cardinal Newman and his “idea of conscience,” which he condemns as being “precisely modernist.”

We have seen, through looking at the chapter in question, that he does not so portray the late Cardinal. It is quite clear from the context of the Letter that Newman is by no means addressing how we attain knowledge of divine revelation, but rather considering – with a correct definition of conscience – whether the dogma of papal infallibility entails Catholics being the moral and mental slaves of the Pope, even in the face of evil commands.

In short, it is clear that Newman did not believe that conscience is “some special faculty in your brain or in your intellect or something like that where you get signals from heaven”, or “[s]ome sort of telephone to Heaven about what’s true and what’s false” – as Bishop Sanborn suggests. Indeed, we cannot help wondering whether the Bishop has actually read the book, chapter or even the actual words which he uses as the basis for his condemnation, or has merely forgotten its content, or misunderstood what is said. Either way, condemnations and criticisms made on the basis of a text which one has not read, remembered, or understood, are not of very great weight.

But what of the Bishop’s other criticisms? Does Newman’s use of language undermine what we have presented here, or suggest that he was simply contradicting himself?

Having discussed the immediate context of the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, we are now in a position to consider particular criticisms, including:

Why did Newman call conscience “the aboriginal Vicar of Christ”?

How is this linked to a proof for God’s existence proposed by Newman – and is this proof sound?

What did Newman mean by toasting “conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards”?

What should we make of Newman’s alleged friendship with the modernist Baron von Hügel?

These shall be the subjects of the two subsequent parts.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

You can see what readers are saying over at our Testimonials page.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Read Next:

Bishop and Cardinal Mini-Series

Part I: Is Cardinal Newman’s idea of conscience ‘precisely modernist,’ as Bishop Sanborn claims?

Part IIa: Bishop Sanborn, and Cardinal Newman’s ‘Proof from Conscience’

Part III: Bishop Sanborn’s attempt to link Cardinal Newman with Baron von Hügel

Books

Newman – Letter to the Duke of Norfolk

Newman – An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine

Newman – The Idea of a University

Bishop E.T. O’Dwyer – Cardinal Newman and the Encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis

Fr E.D. Benard – A Preface to Newman’s Theology

C. Michael Shea – Newman's Early Roman Catholic Legacy, 1845-1854

Articles

See our Newman archive here – with some highlights below:

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

MHT Seminary, ‘Questions for the Rector | Ep. 5: The Barron/Shapiro Interview’, YouTube, 7 Nov 2023. The comments start around the 12 minute mark. I will not be continually offering references and timestamps – this should be sufficient.

We could also note in passing that in this video, the Bishop states that “most theologians” held the position that only two dogmas (God’s existence and his judgement) needed to believed explicitly as a necessity of means for salvation, rather than four (the Holy Trinity and Christ’s incarnation/redemption). The Dominican moralists McHugh and Callan disagree, stating:

“A majority of theologians hold, and with greater probability it seems, that since the promulgation of the Gospel it is necessary for adults to know and accept [also] the two basic mysteries of Christianity— viz.:

That in God, who is our beatitude, there are three persons (the Trinity), and

That the way to our beatitude is through Christ our Redeemer (the Incarnation).”

Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton agrees with McHugh and Callan, stating:

“Now most theologians teach that the minimum explicit content of supernatural and salvific faith includes, not only the truths of God’s existence and of His action as the Rewarder of good and the Punisher of evil, but also the mysteries of the Blessed Trinity and the Incarnation.”

We could also note that the Holy Office has stated that the safer position (four dogmas) must be followed in practice in relation to the administration of baptism. For example, in 1703, it answered a dubia submitted by the Bishop of Quebec:

“Whether a minister is bound, before baptism is conferred on an adult, to explain to him all the mysteries of our faith, especially if he is at the point of death, because this might disturb his mind. Or, whether it is sufficient, if the one at the point of death will promise that when he recovers from the illness, he will take care to be instructed, so that he may put into practice what has been commanded him.

“Resp. A promise is not sufficient, but a missionary is bound to explain to an adult, even a dying one who is not entirely incapacitated, the mysteries of faith which are necessary by a necessity of means, as are especially the mysteries of the Trinity and the Incarnation.” (Denzinger 1349a)

It gave a similar answer to a similar question later that year:

“Resp. A missionary should not baptize one who does not believe explicitly in the Lord Jesus Christ, but is bound to instruct him about all those matters which are necessary, by a necessity of means, in accordance with the capacity of the one to be baptized.’ (Denzinger 139b)

While the administration of baptism is not exactly the same question, it is instructive – and the Holy Office’s explanation also shows that they held that belief in the Holy Trinity and Incarnation were “necessary by a necessity of means.”

A detail: Edmund Voit SJ, a moral theologian writing in 1769, who himself seems to lean towards the laxer position, states (as is typical) that the stricter position “must be held in practice precisely because the question concerns the essentials necessary for salvation with the necessity of means.” But from this he draws an interesting, and yet obvious, conclusion about how these matters should be presented in catechesis and sermons:

“[I]n catechesis, it is preferable to teach that the knowledge of the mystery of the Trinity and the incarnation of Christ is absolutely necessary […] Pope Benedict XIV advises that this explicit faith regarding the necessary means and precepts should be explained primarily in catechisms and sermons.”

It does seem that the frequent presentation of the laxer position (especially as a “default”) is not conducive to evangelisation or indeed the salvation of souls.

Further, while many clerics may well act on the stricter position in certain respects (such as when it comes to administering the sacraments), the tenor of many discussions of the topic makes it hard to see that it is “held in practice.” If it was, then surely fewer would talk to the faithful about the laxer position at all, let alone present it as if it were the “default” or more probable opinion.

McHugh & Callan – Moral Theology – A Complete Course Based on St. Thomas Aquinas and the Best Modern Authorities, n. 787(b). Online at Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive here and here – relevant section here:

Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton, ‘The Holy Office Letter on the Necessity of the Catholic Church’, p 459. In The American Ecclesiastical Review, Dec. 1952, Vol. 127, No. 6, pp 450-461. Available at https://archive.org/details/sim_american-ecclesiastical-review_1952-12_127_6/page/459/mode/1up

Denzinger, Sources of Catholic Dogma’, taken from https://patristica.net/denzinger/

Edmond Voit SJ, Theologis Moralis, Pars Prima, p 226-7. Stahel, Wirceburgi, 1769.

https://www.newmanreader.org/biography/ward/volume2/chapter25.html, pp 166, 167, 179

Pope St Pius X, March 1908. Available at https://newmanreader.org/canonization/popes/acta10mar08.html – which gives the following reference: English translation, provided by Michael Davies, also included in Davies’ Lead Kindly Light: The Life of John Henry Newman, Neumann Press, 2001.

Ibid.

In discussing a text of St Augustine, which Newman took as his motto as a cardinal, Pius XI called Newman ‘a man of high fame and noble nature.’

As for Pius XII, he wrote a letter to the Archbishop of Westminster commemorating the centenary of Newman’s conversion. In this letter, he said of Newman:

‘The pride of Britain and of the universal Church’

‘One quality especially seems to Us to call for close attention and study in the career of the great man whose happy return to the Christian fold you are commemorating. He ‘gave up his whole life to the truth’ (Juvenal. Sat. iv. 91); all his efforts, all his untiring labours, were dedicated to that end […] He held to it ever afterwards with unshaken consistency, made it the guiding principle of his whole life, found in it, as in nothing else, full contentment of mind.’

‘There can be no doubt that the evocation of so great a memory will have great value for those who already rest in the bosom of the Catholic Church, already enjoy Christian teaching in its entirety. But We think it will be equally valuable to those persons, not rare in your own country, who are in search of the uncontaminated tradition of heavenly truth.’

‘Towards all these Our heart goes out in fervent love; what heavenly joys of consolations can We best ask for them, foresee for them? The same, surely, in which John Henry Newman, resting now from all those troubles, cares and anxieties, found at last, even in this earthly exile, happiness, and refreshment, and content.’

Pius XI text taken from Rev. Thomas A. Becker, S.J., in The Catholic Mind, vol. 28, No. 17, September 8, 1930, p. 342, available at https://www.newmanreader.org/canonization/popes/acta1may30.html

Pius XII, Letter to the Archbishop of Westminster, in The Tablet, 13 October 1945, Vol. 186. Available at https://www.newmanreader.org/canonization/popes/tablet13oct45.html

Dom Cuthbert Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 1806-1889, Vol. II, p 88. Benziger, New York, 1926.

Wilfrid Ward, Life of Cardinal Newman, Vol. 2, p 406. Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1912. Available at Newmanreader.org

Ibid., 407.

Dom Cuthbert Butler, The Life and Times of Bishop Ullathorne, 1806-1889, Vol. II, pp 101-2. Benziger, New York, 1926.

Ibid., 102.

Ibid., p 102.

John Henry Newman, Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, 1875. Published in Certain Difficulties felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching Considered, Vol. II, p 261. Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1900. Available at https://www.newmanreader.org/works/anglicans/volume2/gladstone/section5.html

St Pius X, ibid.

Ibid.

Newman 1875, p 256

Ibid., 246-7

Ibid., 246

Ibid., 249-50

Ibid., 275.

Ibid., 256-7

Ibid. 257.

The point continues:

“These have always been recognized as infallible by the doctors of the Church, and on that account, could never become the object of a “resistance.” For in these the faithful cannot be mislead, lest the words of Pope Leo XIII become true:

“‘If it could in any way be false, an evident contradiction follows; for then God Himself would be the author of error in man. ‘Lord, if we be in error, we are being deceived by Thee.”’”

Fr Damien Dutertre, The Errors Of The “Recognize And Resist” System, 2022. Now included without authorial attribution as Chapter XI on TheThesis.us, accessible at https://web.archive.org/web/20231115094847/https://thethesis.us/chapter-xi/

Newman 1875, 257-8.

Ibid., 258.

Ibid., continuing with considerable length, pp 258-261.

Newman contiues:

The word ‘Superior’ certainly includes the Pope; Cardinal Jacobatius brings out this point clearly in his authoritative work on Councils, which is contained in Labbe’s Collection, introducing the Pope by name:— ‘If it were doubtful,’ he says, ‘whether a precept [of the Pope] be a sin or not, we must determine thus:—that, if he to whom the precept is addressed has a conscientious sense that it is a sin and injustice, first it is duty to put off that sense; but, if he cannot, nor conform himself to the judgment of the Pope, in that case it is his duty to follow his own private conscience, and patiently to bear it, if the Pope punishes him.’”

Ibid., 261.

https://catholicism.org/ad-rem-no-473.html

In this article the question is treated whether explicit faith in Christ is necessary for justification. The introduction specifies the state of the question, lays out the thesis that is being defended, and gives the reasons for the scholastic format of the article. The objections are then stated. The arguments stem from both speculative and positive theology involving all possible sources: Scripture, Magisterium, Church Fathers, etc. The respondeo affirms explicit faith in Christ as a necessity of means for justification, insisting on the gratuity and supernaturality of salvation. The contrary opinions of some later theologians are then briefly exposed. Lastly the objections are each answered individually.