Final nail in the Bellarmine 'resistance quote' coffin?

Cajetan, whom Bellarmine cites in the famous resistance quote itself, provides the definitive context against a 'Recognise and Resist' interpretation.

Cajetan, whom Bellarmine cites in his famous resistance quote itself, provides the definitive context against a 'Recognise and Resist' interpretation.

Editor’s Notes

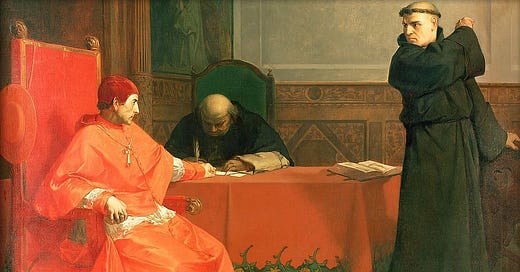

The following text is by Cardinal Thomas de Vio Cajetan OP (1469–1534). It is taken from Chapter 27 of his treatise On the Authority of Pope and Council—the very chapter cited by St Robert Bellarmine in his well-known “resistance quote.”

Cajetan was a renowned commentator on St Thomas Aquinas and one of the most influential scholastic theologians of his time. His writings on papal authority remain significant, particularly in debates concerning the extent of obedience owed to a pope.

In discussing “resistance to the pope,” Bellarmine refers readers to two specific treatments on resisting a pope—one from Cardinal Torquemada, the other from Cardinal Cajetan. In light of these texts—Bellarmine’s chosen context for his own comments—the idea that the saint was proposing a “recognise and resist theology” is manifestly untenable.

Misuse of these texts

The “Bellarmine resistance quotes” (there are two) are ubiquitous in traditionalist discourse. Many assume that they support the idea that:

A pope can attempt to destroy the Church through heresy, false worship, or evil laws.

Such a pope remains legitimate despite these acts.

The faithful must resist his errors while recognising his authority.

However, these ideas are not found in Bellarmine himself, nor in Cajetan, or Torquemada, his chosen reference points. The assumption that the texts in question justify resisting a pope who spreads heresy is based on a misapplication of their arguments.

In reality, both Cajetan and Torquemada explicitly exclude the possibility of a pope teaching heresy or imposing false worship. Their discussions concern only a pope who, while still Catholic, governs immorally or tyrannically. This omission is deliberate, not incidental; this means that applying their comments on resistance to a heretical pope is a misuse of the sources.

The relevant texts

To clarify this, we are presenting the texts to which Bellarmine refers.

We have already provided Torquemada’s treatment of the issue.

We also provided Chapter 24 of Cajetan’s work, which raises the objections that he later answers in Chapter 27.

What follows is Chapter 27 itself. In this chapter, Cajetan is considering whether a pope can be deposed for any reason other than heresy.

In this work, Cajetan argues that a heretic pope should be deposed, but is not deposed ipso facto. He later leaned toward the “second opinion,” which holds that a heretical pope is already deposed (even for secret heresy). In his treatment of the subject, St Robert Bellarmine gives an overview of these ideas, and refutes both the second and fourth opinions.

Regardless of the state of that question, Cajetan repeatedly emphasises that this chapter is dealing with whether a “destroyer pope” who still has the faith can be deposed—not one who has already fallen into heresy.

What Cajetan actually says—his central argument

Cajetan answers firmly that a pope who retains the faith cannot be deposed for any reason.

Throughout Chapter 27, he explains the alternatives available to Catholics faced with such a pope. These include:

Refusing obedience to sinful commands.

Publicly resisting unjust acts.

Invoking divine intervention through prayer.

However, he explicitly denies that this resistance amounts to judging or deposing the pope. Deposition, he argues, is only possible in the case of heresy—because heresy fundamentally changes the pope’s state.

Evil popes vs heretic popes

This chapter clarifies Bellarmine’s text and reveals the precise nature of the destruction that Cajetan said could be resisted.

Chapter 27 concerns only the case of a pope who, while evil or destructive, remains a Catholic.

It might be objected that a non-heretical pope could still attempt to destroy the Church by teaching heresy. Cajetan explicitly rejects this possibility. In the final section of Chapter 27, he states that a pope who teaches heresy is, in the eyes of the Church, a heretic, and can be deposed. The closest that Cajetan comes to addressing “R&R” ideas is when he states the following against some of their presuppositions, by affirming the legitimacy of a cognitive judgement of heresy under certain circumstances:

By natural law, it is likewise required that a person be able to discern what appears externally (1 Kings 16.7); and thus, if manifestly heretical acts are observed (such as statements that evidently express heresy outright), and if these acts and statements are made in such a way that it can, from a human point of view, be judged that the conscience gives its consent to them, in these conditions one must judge that the person is a heretic.

All in all, Cajetan entirely excludes papal claimants who fall into heresy or attempt to teach heresy.

The same exclusion is evident in:

The objections raised in Chapter 24 (which Chapter 27 answers).

The Fifth Response (on prayer) of Chapter 27, which we have published separately for ease of reading.

Examples of papal destruction which Cajetan considers

Cajetan provides several examples of how a pope might attempt to “attack” the Church—none of which involve heresy:

Tyrannical rule – Acting violently against the Church.

Simony – Selling ecclesiastical offices and benefices.

Squandering Church resources – Using the wealth of the Church for personal or familial gain, even demolishing sacred buildings for private projects.

Dismantling the hierarchical order – Deposing all bishops or undertaking other acts that would cause disorder in the Church.

General corruption and scandal – Acting in a morally reprehensible or scandalous way.

Ignoring correction – Refusing to amend his actions despite all human efforts.

Exceeding his authority – Acting as though the Church exists for him rather than he for the Church.

What is absent? Cajetan never considers a scenario in which a true pope:

Teaches heresy

Promulgates evil laws (including false worship) universally

Imposes a false religion

These ideas are conspicuously missing from Cajetan, Torquemada, and the Bellarmine texts often cited in support of “R&R”.

What Cajetan says about heresy as a change of state

The reason for this exclusion is clear. Cajetan argues that a pope who retains the faith cannot be judged or deposed for any crime, no matter how scandalous.

He acknowledges one exception to the injudicability of the Roman Pontiff: heresy.

Heresy, he explains, changes a man’s state, transforming him from a Christian into a non-Christian. This is why (according to Cajetan) a heretical pope can be judged and deposed, while an evil but still Catholic pope cannot be.

Permissible resistance vs. deposition

Cajetan permits resistance only in certain ways:

Withholding obedience in sinful matters

Refusing to implement illicit commands

Publicly denouncing abuses

Praying for divine intervention.

But he explicitly denies that the pope can be forcibly removed for these crimes. Deposition, in his framework, applies only to a pope who has lost the faith.

No justification for ‘Recognise and Resist’ in this text

Since Cajetan does not consider a scenario where a pope teaches heresy while remaining a valid pope, these writings cannot be used to justify resisting a pope’s heretical teachings while recognising his authority.

Instead, his argument implies the opposite: if a pope teaches heresy, he is a heretic, and he must be deposed.

Implications and Conclusion

Traditionalists cannot use this chapter to justify “R&R theology.” It is simply not discussing a pope teaching heresy while remaining legitimate.

Cajetan’s actual opinions on the pope heretic question—although false, and soundly refuted by Bellarmine—show why this chapter cannot justify “R&R theology.” The “fourth opinion” does not hold that a heretical pope must be resisted, or that alternative emergency ministries should be established until he comes to his senses; it holds that he must be deposed.

Those who claim to hold the fourth opinion today do not act on it. Cajetan provides no justification for indefinite resistance to a heretical pope, or one who imposes heresy, errors, evil laws and a new religion on the Church.

Resistance without moving towards deposition is not an option in Cajetan’s framework.

Why is it that the advocates of the fourth opinion—or of other opinions such as the “sixth” or that of John of St Thomas—are not working towards the actual deposition these theologians discuss?

See also: