Christ’s silence in his Passion—and in his Church

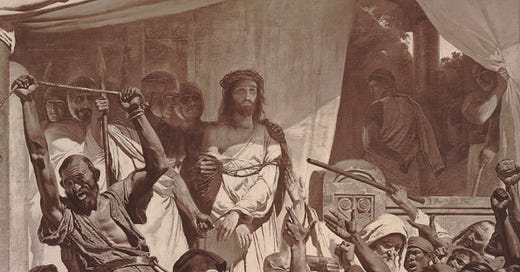

The Church stands before the world, as Christ stood before Pilate to be judged—and she stands in silence.

Our Lord begins to be sorrowful

“He began to grow sorrowful and to be sad. Then he saith to them: My soul is sorrowful even unto death. Stay you here and watch with me.”1 (Matthew 26.37-8)

When Our Lord went to the Garden of Gethsemane, the gospels say that he “began” to be sorrowful. St Mark adds that “he began to fear”: before this, there is no trace of fear in him whatsoever. Even at the Last Supper, his disciples are more afraid and sad than he is.

This is because, as the Gospels indicate, he had not yet “begun”—in an active sense. John Henry Cardinal Newman wrote the following:

“He was always Himself. His mind was its own centre, and was never in the slightest degree thrown off its heavenly and most perfect balance. What He suffered, He suffered because He put Himself under suffering, and that deliberately and calmly. […]

“He said, ‘Now I will begin to suffer,’ and He did begin.

“His composure is but the proof how entirely He governed His own mind. He drew back, at the proper moment, the bolts and fastenings, and opened the gates, and the floods fell right upon His soul in all their fulness. […]

“You see how deliberately He acts; He comes to a certain spot; and then, giving the word of command, and withdrawing the support of the God-head from His soul, distress, terror, and dejection at once rush in upon it. Thus He walks forth into a mental agony with as definite an action as if it were some bodily torture, the fire or the wheel.”2

This agony became so severe that he began to sweat blood.

By the time that Judas arrives, Our Lord appears to have mastered this sorrow—although as we shall see in the next part, this sorrow continues. Nonetheless, he spends almost all of his Passion in a composed and dignified silence.

The silence of Christ

From Gethsemane to Golgotha, Christ endures manifold indignities in silence—just as it was foretold by the prophet Isaias:

“He was offered because it was his own will, and he opened not his mouth: he shall be led as a sheep to the slaughter, and shall be dumb as a lamb before his shearer, and he shall not open his mouth.” (Isa. 53:7)

Sr Teresa Gertrude (d. 1889), an English Carmelite and convert, suggests in her work Jesus the All-Beautiful that both Christ’s silence and his rare words are all for us:

“He accomplished in silence all that had been foretold of Him, with the exception of a few instances in which His Divine wisdom and His yearning after their souls prompted Him to remind the people of what had been written concerning Him, and to point out that its fulfilment had already taken place before them.

“When indeed He spoke of His sorrows, or confessed their heavy weight by the words He uttered, it was with some definite object in view for the instruction of those who heard Him, so great was His love for them and desire to gain their sympathy. But we may be assured that there was a large proportion of suffering endured by our Lord regarding which He sealed His lips.”3

Every time Our Lord does break this silence, his words come unexpectedly—and always with power.

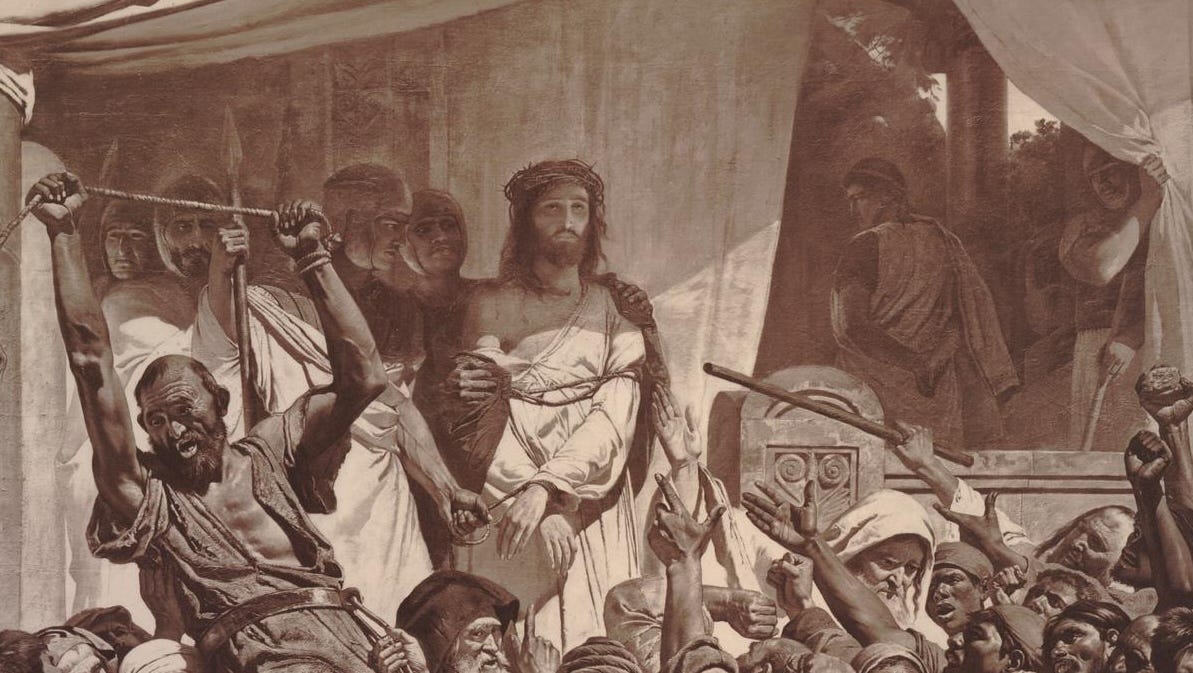

Consider the reaction of Pilate to the scourged Christ, crowned with thorns. Despite being no stranger to brutality, he is visibly disturbed when he sees him, and asks him questions which are clearly filled with anxiety.

As the questions continue, Pilate is almost begging the silent Christ to answer him, appealing to his power to crucify or liberate him. Then, unexpectedly, Our Lord breaks his silence and tells Pilate in perfectly lucid terms:

“Thou shouldst not have any power against me, unless it were given thee from above. Therefore, he that hath delivered me to thee hath the greater sin.” (John 19.11)

These words strike Pilate so deeply that St John immediately adds:

“[F]rom henceforth [he] sought to release him.” (19.12)

Other sudden breaks of silence include his rebuke of the soldier who struck him before Caiphas, and his words to the women of Jerusalem who wept for him.

The most surprising break of all is at the moment of his death, in which he cries out “with a loud voice.” Our Lord is not shouting in pain: crucified men are incapable of this. St Luke specifies that this “cry” even consisted of articulate words:

“Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit.” (Luke 23.46)

Of this cry and these words, St John Chrysostom says:

“He cried out with a loud voice to shew that this is done by His own power. For by crying out with a loud voice when dying, He shewed incontestably that He was the true God; because a man in dying can scarcely utter even a feeble sound.”4

Each of these moments reveals the same truth: however it may appear, Christ is always the master, in control of each situation. He is never overwhelmed. He suffers what he chooses to suffer, because it is his own will to do so.

St Ignatius of Loyola urges his retreatants not only meditate on Christ’s suffering, but to recognise that “he desires to suffer”; that he hides his divinity, which “could destroy its enemies and does not do so”; and that he suffers all this out of love for each individual man, to atone for each one’s sins.5

Newman points to this mystery of his moment of death:

“[W]hen the appointed moment arrived, and He gave the word, as His Passion had begun with His soul, with the soul did it end. He did not die of bodily exhaustion, or of bodily pain; at His will His tormented Heart broke, and He commended His Spirit to the Father.”6

The agony of Gethsemane continued throughout the whole of the Passion. Christ’s silence might make us think that this agony had passed altogether—but no: underneath this silence and composure, the suffering continues.

His silence and composure were a source of wonder in those who witnessed it. They should be a source of wonder for us too, and draw us to contemplate in faith and love.

And it should prepare us to consider how this same silence is now lived by his Church.

The silence of the Church

St Augustine writes that “[Christ] is the Head of the Church, and the Church is His Body, [and the] Whole Christ is both the Head and the Body.”7 The Church is not merely his institution—she is Christ still living on earth.

And just as the Head lived a life of suffering and glory, so too does the Body. In Mystici Corporis Christi, Pope Pius XII teaches that Christ:

“Christ our Lord wills the Church to live His own supernatural life, and by His divine power permeates His whole Body and nourishes and sustains each of the members according to the place which they occupy in the body, in the same way as the vine nourishes and makes fruitful the branches which are joined to it.”8

In another sense, as detailed by Mgr Robert Hugh Benson in his Christ in the Church, the Church lives out the events of Christ’s life simultaneously in her members. At any given time, in her members:

“He is born here, lives, suffers, dies, and eternally rises again on the third day.”9

Many today believe that the Church mystically re-lives the life of Christ in a linear way through history. In fact, she will always be enduring a Passion in some of her members—but it seems that she is currently re-living his Passion in a special way. This suffering is not just endured by individuals or scattered communities—it seems to envelop the Church as a whole.

In a particular way, she appears to be re-living the silence of the Passion. She stands before the world, as Christ stood before Pilate, to be judged—and she stands in silence.

In this silence, the sheep are left without access to that sure rule of faith, by which she forms, directs and protects us. The very existence of so many online projects and apostolates, as well as “irregular” chapels, testify to the impossibility of trusting those who are supposedly our authorised shepherds.

Our Lord said of himself, in the third person:

“[T]he sheep follow him, because they know his voice. But a stranger they follow not, but fly from him, because they know not the voice of strangers.” (John 10.4-5).

And yet today, those who claim to speak for the Church often sound more like strangers than shepherds. The sheep do not follow them—and neither do the goats, who praise them only when convenient. Many of these would-be pastors bear more resemblance to the strangers or to the thief of the parable:

“The thief cometh not, but for to steal and to kill and to destroy.” (John 10:10)

In Christ’s day, what was considered remarkable was that he taught “as one who having authority”. But what astonishing about these strangers—and even revealing—is their rejection of their own pretended authority. As Romano Amerio put it in his classic book Iota Unum:

“The internal fact producing [today’s disunity] is the renunciation that is, the non-functioning, of papal authority itself, from which the renunciation of all other authority derives.”10

Whichever of the many explanations best fit this absence and non-functioning of authority, this “silence” is the very essence of the crisis both in the Church and in civil society. Those who “teach” without authority and without the message of Christ do not make their voices recognisable as his shepherds, speaking for the Church.

As such, despite the proliferation of words and letters, the absence of strong, authoritative teaching of the faith is equivalent to the Church herself keeping her silence. The Church, like her Lord, remains silent in the hour of judgment.

What does it mean?

Why, we might ask, does Christ seem not to speak to us through his Church at present? Why does he not defend himself, and her?

We might be tempted to echo the apostles, “Master, doth it not concern thee that we perish?” (Mark 4.38).

Or, more daringly still, his word from the Cross: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

Sr Teresa Gertrude’s reflections on the mystery of Christ’s silence may help us understand something of the Church’s apparent silence today. She acknowledges how hard it is to understand why Christ chose not to speak in his Passion: why he allowed false witnesses to misrepresent him and his teaching; why he worked no miracle before Herod, though it might have converted many; and why he allowed this silence to bring further contempt on himself, even “to His being clothed in the garment of a fool.”11

Surely, we might think, this silence scandalised many who would have believed—if only he had spoken. But he speaks little during this time, and only to a few.

And yet while human judgment might call out for Our Lord to defend himself, even Pilate could tell that more was happening than human judgment could understand. Sr Teresa Gertrude continues:

“[W]e must certainly feel sure that nothing less than the wisdom of one Who was Divine, and of a Soul replenished with the gifts of the Holy Spirit, could have justified silence in a matter wherein the glory of God itself seemed to require that it should no longer be maintained. […]

“A multitude of reasons appear in our eyes to have demanded the infringement of that rule of silence which He had imposed upon Himself.

“But no! save where the glory of His Father and the Divinity of His own Person were concerned, our Lord preserved, from the moment of His arrest in the Garden, His passive attitude unchanged, as being most consonant with His manifestation of the majesty, the wisdom, and withal the patient inexhaustible love of a rejected God.”12

Just as the Church veils her images in Passiontide, so too does Christ’s silence veil the movements, thoughts and sufferings of his Sacred Heart in the Passion.

In our day, in the face of the Church’s silence, we too are left standing before this veil of silene—like Our Lady, St Mary Magdalene and St John—looking on in amazement and dismay.

But if we have learnt to love the Church, especially as presented to us on Laetare Sunday, then this silence, rather than making us despair, becomes a new opportunity for us to make acts of faith, hope and charity. It becomes an opportunity for us to stand by Christ in his silence, as he is once more tried, judged and condemned in his Church.

Conclusion—The other side of Christ’s passion

If we had nothing but the Gospels, we would see the most noble of men undergoing unimaginable suffering with dignity and composure.

But the Gospels do not just tell a story about a man in the past. They reveal the living God-Man, whom we must follow and imitate, and in whom we must live and abide. As Dom Eugene Boylan puts it:

“Christ is all and in all. The whole Christ – head and members – resembles Christ the Head. Each member is an image of the Head, for each Christian is another Christ […]

“Each member, and each member’s story, in some way and in some degree, resembles and reflects the Head and the story of the Head – and even the whole Christ and the story of the whole Christ.

“Each tiny chapter of the story re-echoes the end of the whole story so daringly summed up by St. Augustine: And there shall be one Christ loving Himself. For Christ saves us and sanctifies us by making us part of Himself, so that His story is our story also.”13

And in fact, we do have more than the Gospels – we also have a “pearl of great price”, the holy Roman liturgy.

Despite the physical veils over the images, the Church’s Passiontide liturgy actually unveils for us some of what transpired within Christ’s soul during his Passion, and draws us into the union described by Boylan.

On each of the two Sundays of Passiontide, she presents us with a different aspect of the suffering Christ: on Passion Sunday, his composure, and then the depth of his agony on Palm Sunday.

You can read about these two respective presentations below:

This is an updated part of The Roman Liturgy—an ongoing series of standalone pieces about the liturgy, hope, and the crisis in the Church.

This is an expanded and edited version of an article originally published at LifeSiteNews in March 2023.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further Reading:

Dom Prosper Guéranger – The Liturgical Year

Fr Johannes Pinsk – The Cycle of Christ

Dom Columba Marmion – Christ in his Mysteries

Mgr Robert Hugh Benson – Christ in the Church

Fr Frederick Faber – The Precious Blood

Fr Leonard Goffine – The Church’s Year

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

All Scripture and propers taken from the Douay-Rheims-Challoner version. Some liturgical texts amended to reflect the Latin of the propers when there is a slight variation from the Biblical text.

John Henry Newman, ‘Discourse 16. Mental Sufferings of our Lord’, Discourses Addressed to Mixed Congregations, Longmans, Green, and Co. London, 1906, pp 323-341; pp 333-4. Available at https://newmanreader.org/works/discourses/discourse16.html

Sr Teresa Gertrude, Jesus the All-Beautiful, ed. Rev. J.G. MacLeod. Burns and Oates, London, 1910, pp 331-2.

Quoted in St Thomas Aquinas, Catena Aurea, Vol. I, Part II, trans. John Henry Newman, James Parker and Co., Oxford and London, 1874, p 962

St Ignatius Loyola, Spiritual Exercises, n. 195-7. Included in Christian Warfare, Society of St Pius X, 2009.

Newman, 341.

St Augustine, Sermon 87 on the New Testament (Tenth chapter of the Gospel of John), n. 1. Translated by R.G. MacMullen. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 6. Edited by Philip Schaff, Christian Literature Publishing Co., Buffalo, NY, 1888. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Available at http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/160387.htm.

Pius XII, Encyclical Mystici Corporis Christ, 1943, n. 55. Available at: https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_29061943_mystici-corporis-christi.html

Mgr Robert Hugh Benson, Christ in the Church, p 10. The Cenacles Press, Stamullen, Ireland, 2022.

Romano Amerio, Iota Unum – A study of the changes in the Catholic Church in the XXth century, Sarto House, Kansas City MO, 1996. 143.

Sr Teresa Gertrude, 338.

Ibid, 338-9

Dom Eugene Boylan, This Tremendous Lover, Baronius Press, 2019, pp xxi-xxii.