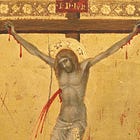

Christ or captivity: Why the devil still rules those outside Christ and his Church

Redemption is not just legal change or covering over—it's an incorporation into Christ, and a liberation from a world ruled by demonic power.

Redemption is not just legal change or covering over—it's an incorporation into Christ, and a liberation from a world ruled by demonic power.

Editor’s Notes

The following text is an edited translation of the third chapter of Fr. Anselm Stolz’s work Theology of Mysticism. The translation has been made by a German friend of The WM Review.

Stolz was a German Benedictine who lived in the first half of the 20th Century and passed from this life at the young age of 41. At the age of 28 he already began teaching systematic theology at the Pontifical Athenaeum of Saint Anselm in Rome. He had a reputation of having a profound knowledge about the theology and philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas.

Fr Stolz develops his thoughts on the atonement from the real incorporation of the individual believer into the redemptive work of Christ. He especially accentuates how all true return to God in our fallen world can only take place in and through the “one mediator of God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim 2:5).

In the presented extract, he focuses on understanding the Redemption in its concrete historical realisation, and shares some interesting points about the essential dogma outside the Church there is no salvation.

The Dominion of the Devil

Fr. Anselm Stolz OSB

We are accustomed, based on Western theology, to primarily view the Redemption as the cancellation of a legal debt to God.

We start from the perspective that sin is an offence against God, a crime against the highest Majesty of the Lord of Heaven and Earth, which must find its corresponding atonement, or for which God, by His will, wants to have this full atonement.

Under this assumption, the Incarnation of a divine person who, as a member of the human race, can make atonement on behalf of others is indeed required. Furthermore, this divine person, due to His divinity, is free from sin and can act in a way that is pleasing to God, giving each of His actions an infinite value corresponding to His divinity.

St Thomas and the Redemption

This understanding of the Redemption is, for example, expressed in St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica. St. Thomas raises the objection to the Incarnation of Christ:

“By sin, human nature was shattered. For its restoration, the satisfaction of a human seemed sufficient. God cannot demand more from man than he can give. Moreover, God is more inclined to have mercy than to punish. Therefore, just as He attributes sin as a debt to humanity, He can also consider it cancelled for the sake of human satisfaction. The Incarnation, therefore, was not necessary for the restoration of human nature.”

This objection contains exactly what we indicated as a characteristic of the Western view of redemption. Sin is a transgression, a debt for which corresponding atonement must be made.

However, God can accept a purely human act as atonement because He cannot demand more than man is capable of providing. St. Thomas Aquinas provides an insightful response to this objection. He says,

“Atonement can be sufficient in whole or in part. The first applies when guilt and atonement are of equal value, meaning they completely balance each other out. In this sense, the atonement of a mere human could not be sufficient because sin has corrupted the entire human nature. Neither the worth of an individual nor that of many individuals could have been offered for the entire race to make amends for the damage.

“Furthermore, the sin committed against God is, in a certain sense, infinite due to the infinity of His divine Majesty. The gravity of an offense increases with the dignity of the offended. Therefore, a fully sufficient atonement required an act of atonement of infinite worth, and only a God-man can accomplish that.”1

Here, the work of redemption is understood from the perspective of an infinitely valuable act to compensate for an infinitely great offense, which only a God-man can provide.

This understanding of the Redemption is entirely correct, and our task here is not to justify its validity based on traditional Church doctrine.

Now, when we also talk about a physical understanding of the Redemption in the following, it is by no means to deny that St. Thomas’ understanding of the Redemption also entails a physical bestowal of grace upon the redeemed. The validity of the well-known juridical understanding of redemption is in no way being denied or diminished. It is just to say that with this understanding, the work of Jesus Christ, as taught by the Church’s tradition, is not fully represented, and additional explanations in a certain sense are necessary, particularly for understanding the account of St. Paul and mystical union in general.

It is evident that in the understanding as it appears, for example, in the case of St. Thomas, a reintroduction of humanity into paradise for the completion of the Redemption would mean something more incidental.

The dominion of the Devil

For St. Thomas, the actual Redemption is fulfilled with the remission of guilt. However, if we consider the consequences of the Fall less from a legal standpoint and more directly in their concrete historical reality, one cannot pass over the expulsion from Paradise as a consequence of sin and the reintroduction into Paradise as the goal of the Redemption. Alongside the inner state of sin in humanity, there is an external parallel of being expelled from the protective, God-prepared paradise into the world. Man is excluded from God’s special protection, and thus, as tradition expresses it, falls under the dominion of the devil.

Even the Council of Trent emphasised this consequence of Original Sin, particularly the “captivity of the devil.” Through sin, man came under the rule and captivity of the devil; he listened to his seductive advice and was thus drawn into the rebellion of the evil angels against God. This aspect must not be overlooked when assessing the actual condition of humanity.

It is not to be understood as if only the personal relationship of humans with God were clouded by sin amidst a world order reconciled with God or behaving neutrally towards Him. Rather, humanity consciously aligned itself with the spirits already separated from God and governing the cosmos. Reunion with God, therefore, is not only the restoration of personal union with God; it is also liberation from the power of demons and an exit from the cosmos dominated by them. This doctrine of the rule of demons over the world has remained alive in the entire church tradition.

This cosmic aspect is also seen in St. Thomas when, following the “holy teachers and the Platonists,” he holds the view that individual physical things are governed by spiritual substances. He also points out with a word from St. John of Damascus that the devil belonged to those angelic orders “which governed the earthly order.”2

Consequently, it is natural that when man lost Paradise, he entered into the domain of the devil and came under his rule. The devil can exert influence on humans and even on the material creation that humans use, which can become an occasion for sin.3

Under these conditions, the Redemption expands into a cosmic event. The entire world must be redeemed, the dominion of demons must be broken, and the supremacy of God must be fully reestablished. In this cosmic event, individual humans also share in their personal redemption.4

The Redemption and holiness

Alongside this cosmic aspect of the consequence of sin and, accordingly, the Redemption, there is also the recovery of personal holiness seen from a particular perspective in the physical understanding of the Redemption.

It starts from the consideration that the state of holiness is synonymous with closeness to God and union with God, while the state of sin is characterized by distance from God and separation from Him. This is why the Incarnation of a divine person in the work of redemption gains special significance. In the Incarnation, the lost union between humanity and God becomes a reality once more.

This helps us understand why traditional theology regards the Incarnation as the starting point for our Redemption, while in the juridical understanding, it is essentially a precondition for a person of the human race to perform acts of infinite value. The God-man naturally possesses union with God; therefore, it can also be transferred from Him to other humans when they become physically united to Him.

However, the meaning of the older understanding of the Redemption is not exhausted by this. The God-man must, in order for His humanity to become a source of sanctification for other humans, completely transform the human nature He has assumed and free it from all the consequences that the Fall had brought upon it. To achieve this, the dominion of demons over humanity must be broken, and human nature must be liberated from the cosmos bound by sin and the devil as prince of this world.

This understanding of the Redemption therefore includes, as necessary stages of the work of the Redeemer: the Resurrection from the dead, the descent into Hell, and the Ascension into Heaven. In the context of the physical understanding of the Redemption, it cannot be said that there is liberation from the yoke of sin as long as one consequence of estrangement from God is not overturned, which means it needs to be physically overcome.

According to the narrative in Genesis, bodily death is to be regarded as a natural consequence of being estranged from God. The God-man, the archetype and fulfiller of the Redemption, must therefore also physically overcome death. He must rise from the dead. It is only in the victory over death that our redemption is completed. The Easter liturgy celebrates this victory: Mors et Vita duello conflixere mirando Dux Vitae mortuus regnat vivus.

Christ’s victory over death is complete. He not only rises from the grave but, as the conqueror of the prince of death, He also liberates the souls of the righteous of the Old Covenant who, imprisoned in the limbo, awaited their liberation through Christ. The descent into Hell and the liberation of the righteous of the Old Covenant are also part of the victory over death, as explained by Thomas Aquinas in his commentary on the Apostles’ Creed:

“But one triumphs completely over an enemy when one not only defeats him on the battlefield but also penetrates into his realm, even into his own house, and takes away his throne and his possessions. Christ had conquered the devil on the Cross… But to triumph completely over him, He wanted to take his throne from him, and in his very own abode, in the underworld, to bind him. Therefore, He descended into the underworld, took away all his possessions, bound him, and carried off his spoils.”

Christ leads the liberated souls from the stronghold of the prince of death to paradise, the dwelling place of the blessed. The early Christian apocryphal texts, which reflect popular piety very clearly, vividly depict the tension of the captives in the underworld, the fear of the prince of death and the devil, the triumphant appearance of the Redeemer, and His victorious entry into paradise. In the iconography of the Eastern Church, this vivid conception of Christ’s victory over the prince of death has persisted to our days, while in our Western tradition, due to a partial emphasis on the juridical aspect of redemption, the significance of the descent into Hell has somewhat diminished.5

The Ascension

The Ascension of the Lord also gains a particular significance in the physical understanding of the Redemption.

We already mentioned that humanity exists within a cosmos subjected to demonic powers.

“For our wrestling is not against flesh and blood; but against principalities and powers, against the rulers of the world of this darkness, against the spirits of wickedness in the high places.” (Ephesians 6:12).

Like a mighty ring, the world of evil spirits surrounds us. The completion of the Redemption requires that human nature is also freed from this encirclement by the God-man. This became a reality in the Ascension of the Lord. Through the Ascension, the ring was pierced, the separating barrier was broken, and Heaven was opened. The glorified humanity of the Redeemer now reigns at the right hand of the Father, outside the accessible cosmos of evil. The liberation from the power of death and the devil is completed in the humanity of the Redeemer.

What is there to be found outside the Church?

These theological foundations are of the utmost importance for understanding the mystical and interpreting the account of St. Paul.

First and foremost, they are significant for assessing the state of humanity outside the work of redemption and the issue of so-called “natural mysticism.” We are easily tempted to view the closeness to God gained through the Redemption as an elevation of a purely natural union with God that we could attain without Christ. A person who possesses only the gifts inherent to their nature and exists within the framework of a non-divine world would naturally feel the need for profound union with God and might attempt to draw near to God.

To what extent their efforts could be successful need not be discussed here. For the moment, it is crucial to recognise that such a position towards God never becomes a reality for humans. There is no purely natural, good world order in actuality. Without Christ, humans are subject to the dominion of the devil. Consequently, the concept of a purely naturally good mysticism is also called into question. Religious historians and psychologists may entertain such a mysticism if they do not stand on the ground of revelation and, therefore, cannot fully comprehend the situation of the non-Christian person in all its concreteness.

It is true, of course, that God is immediately present in the soul of the sinner due to His omnipresence. But attempting to reach a “mystical union with God” based solely on this omnipresence, apart from everything else, implies that our relationship with God can be “normalised” without Christ.

However, this is not the case. Without Christ, humanity is under the dominion of demons, from which they cannot free themselves. The statement “Extra ecclesiam nulla salus“, outside the Church there is no salvation, therefore also implies another: “Outside the Church, there is no mysticism.” To accept a purely natural mysticism means to deny the belief in the dominion of the devil over unredeemed humanity.

Read next:

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Summa Theol. III Q. 1 Art. 2 ad 2.

Summa Theolog. I. Q. 110 Art. 1 ad 3.

R. Maritain, Le prince de ce monde 1932 p. 12.

“The redemption experienced by the believer is not an event that occurs separately between him, God, and Christ, but a world event in which he participates. Without taking into account the cosmic condition of the concept of Redemption in primitive Christianity, it is impossible to form a correct picture of his (St. Paul’s) faith.”

A. Schweitzer, Die Mystik des Apostels Paulus [The Mysticism of Paul the Apostle] 1930 p. 56.

H. Detzel, Christliche Ikonographie I [Christian iconography I]1894 S. 459 ff.

Thanks for this fascinating article!

I would like to learn more about the “powers and principalities” and about the unseen world in general as is taught by the Church.

It is essential for us to know our Enemy and to know the “spiritual terrain and situational realities” of our life of warfare against the Evil One - I am so done with the Devil’s Enlightenment/Positivist psyops, with his “nothing to see here, move along” B.S. campaign, when reality plainly demonstrates the degradation and death that our (even unwitting) cooperation with his ongoing rebellion continues to wreak in our world.

Any recommended reading? Thanks!