Eastern Orthodoxy? 'The Schismatic Papacy' and Guettée's absurd imposture

Orestes Brownson begins his destruction of the 'Eastern Orthodox' polemic of Abbé Vladimir Guettée against the Catholic Church and the papacy.

Editors’ Notes

This is the first part of a serialisation of Orestes’ Brownson’s engagement with “Eastern Orthodoxy.”

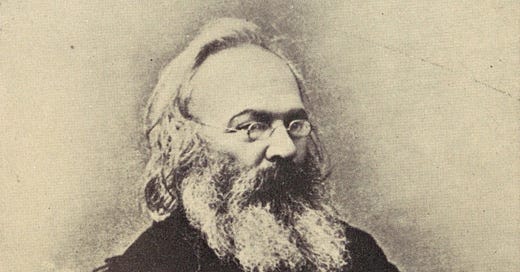

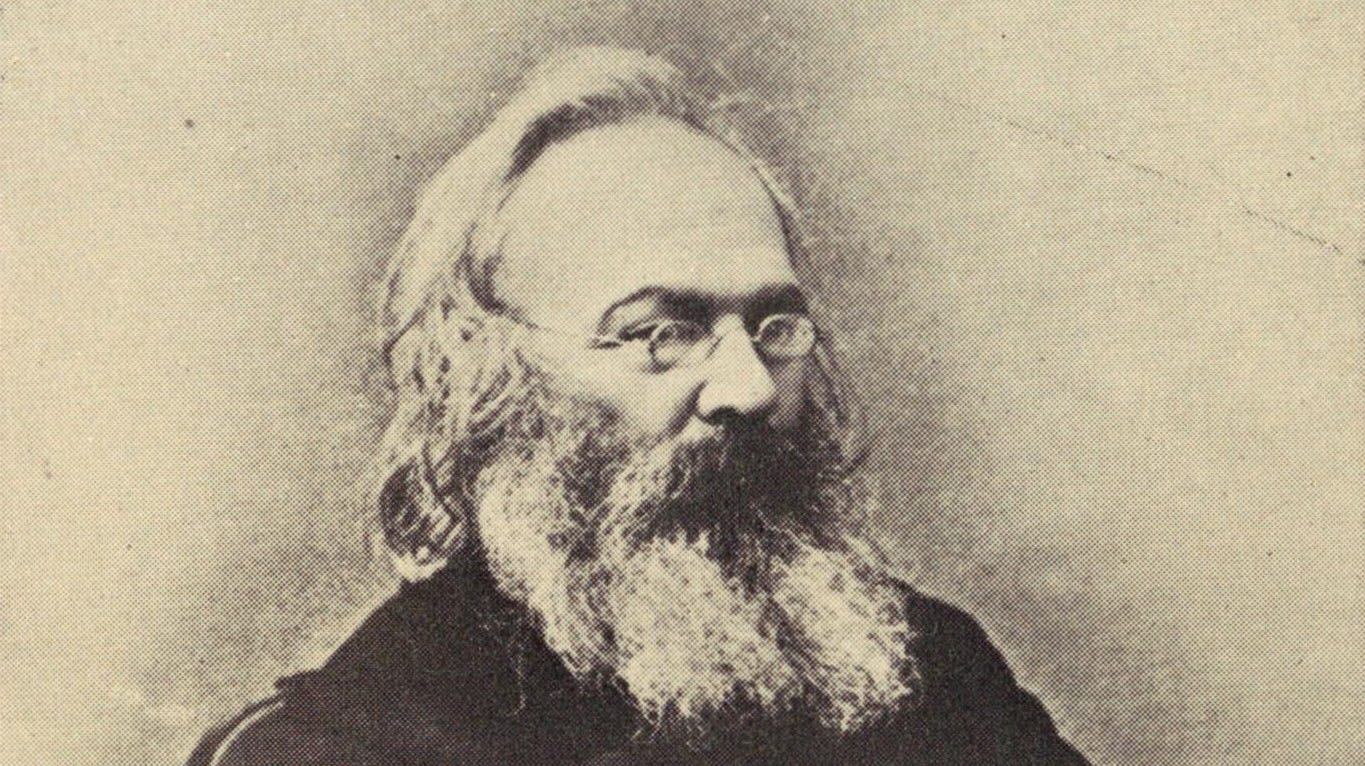

In 1867, the American Catholic writer Orestes Brownson reviewed the book La Papauté schismatique (“The Schismatic Papacy”—rendered in the title of the review “The Papacy Schismatic”), by the schismatic priest Wladimir Guettée’s

As the title suggests, this book was alleging that the papacy was schismatic.

Guettée, born René-François, was a French Catholic priest, who (it seems) was ever somewhat heterodox. At length, he departed into the Photian schism and heresy of the so-called “Eastern Orthodox.” He took the name Wladimir, exercised a priestly ministry amongst the schismatics, and wrote books against the true Church of Christ.

In his review, which came in two parts, Brownson destroys Guettée’s polemic. Due to the length, we will be publishing it in several more parts than that.1

In this part, Brownson is mainly pre-occupied with considering how Guettée has been presented to the public in an absurdly built-up way—and exposing the truth. As a result, he is not directly engaged with the claims of the schismatic “Eastern Orthodox” in this part. This comes later in the subsequent parts of the review.

One key idea in this first part, applied to Guettée and his self-inflicted poor formation, is the following:

“Most of the errors into which men fall arise from the attempt to solve questions without the necessary preparatory knowledge and discipline.”

This is very true, and horribly visible in our day, in most walks of life—but especially in religious matters.

In the face of those encouraging Roman Catholics to enter into schism and heresy, we publish Brownson’s piece in good will, and in the hope that they will instead return to the Church of Christ, outside of which there is absolutely no salvation whatsoever.

Guettée’s ‘The Schismatic Papacy’

Part I—The Abbé Guettée’s Absurd Imposture

Orestes Brownson

Originally published as “Guetté’s Papacy Schismatic’2

From The Catholic World, 1867

Published in The Works of Orestes A. Brownson, Vol. VIII

Thorndike Nourse, Deroit, 1884. pp 474-483

Headings and some line breaks added by The WM Review

Introduction

This Volume [The Papacy, by Guettée] purports to be the translation of a late French work entitled, La Papauté Schismatique; ou Rome dans ses Rapports avec l’Eglise Orientale. Why the translator or editor has changed the title we know not, unless it has been done to disguise the real character of the work, and induce Catholics to buy it under the impression that it is written by a learned divine of their own communion.

Whether equal liberty has been taken with the text throughout we are unable to say, for we have not had the patience to compare the translation with the original, except in a very few instances; but there is in the whole get up of the English work a lack of honesty and frank dealing.

The Introduction to Guettée’s work

On the title-page we are promised an Introduction by the Protestant Episcopal Bishop of Western New York, but in the book itself we find only the “Editor’s Preface” of a few pages. Even this preface lacks frankness, and seems intended to deceive. “The author of this work,” writes the editor, “is not a Protestant. He is a French divine reared in the communion of Rome, and devoted to her cause in purpose of heart and life.” This gives the impression that the author is still a member, and a devoted member, of the communion of Rome, which is not the case.

“But his great learning having led him to conclusions contrary to those of the Jesuits, he fell under the ban;” that is, we suppose, was interdicted. This carries on the same deception, making believe that he was interdicted because he rejected some of the conclusions of the Jesuits, while he remained substantially orthodox and obedient to the church, a thing which could not have happened, unless he had impugned the Catholic faith, the authority, or discipline of the church in communion with the apostolic See of Rome.

We read on: “Proscribed by the papacy… he accepts at last the logical consequences of his position… receiving the communion in both kinds at the hand of the Greeks in the church of the Russian Embassy at Paris.” Why not have said simply: The author of this work was reared in the communion of Rome, but, falling under censure for opinions emitted in his writings, he left that communion, or was cut off from it, and has now been received into the Russian Church, or the communion of the non-united Greeks, and has written this book to prove that the communion that has received him is not, and the one in which he was reared is, schismatic? That would have told the simple truth; but we forget, the editor is a poet, and accustomed to deal in fiction.

Guettée’s biography

The editor, who has a rare genius for embellishing the truth, tells us that “the biographical notice prefixed to the work… gives assurance of the author’s ability to treat the subject of the papacy with the most intimate knowledge of its practical character.” It does no such thing, but, on the contrary, proves that he never was devoted in purpose and life to the communion of Rome, and that even from his boyhood he assumed an attitude of real though covert hostility to the papacy.

His first work was a history of the church in France, the plan of which was conceived and formed while he was in the seminary, and that work is hardly less unfavorable to the papacy than the one before us. Its spirit is anti-Roman, anti-papal, full of venom against the popes, and he appears to have carried on his war against the papacy under the guise of Gallicanism, till even his Gallican bishop could tolerate him no longer, and forbade him to say mass.

His biographer gives a fuller insight into his character, perhaps, than he intended. “From a very early age,” he says, “his mind seems to have revolted against the wearisome routine” of instruction prescribed for seminarians, “and, in its ardent desire for knowledge and its rapid acquisition, worked out of the prescribed limits… and read and studied in secret.” That is, in plain English, he was impatient of direction in his studies, revolted against making the necessary preparation to read and study with advantage, rejected the prescribed course of studies, and followed his own taste or inclination in broaching questions that he lacked the previous knowledge and mental and spiritual discipline to broach with safety.

There are questions in great variety and of great importance which it is very necessary to study, but only in their place, and after that very routine of studies prescribed by the seminary has been successfully pursued. Most of the errors into which men fall arise from the attempt to solve questions without the necessary preparatory knowledge and discipline. The studies and discipline of the college and the seminary may seem to impatient and inexperienced youth wearisome and unnecessary, but they are prescribed by wisdom and experience, and he who has never submitted to them or had their advantage feels the want of them through his whole life, to whatever degree of eminence he may have risen without them. It is a great loss to any one not to have borne the yoke in his youth.

“Most of the errors into which men fall arise from the attempt to solve questions without the necessary preparatory knowledge and discipline.”

It is clear from M. Guettée’s biography that he never studied the papal question as a friend to the papacy, and therefore he is no better able to treat it than if he had been brought up in Anglicanism or in the bosom of the Greek schism.

He is not a man who has once firmly believed in the primacy of the Holy See, and by his study and great learning found himself reluctantly forced to reject it; but is one who, having fallen under the papal censure, tries to vindicate himself by proving that the pope who condemned him has no jurisdiction, and never received from God any authority to judge him.

He is no unsuspected witness, is no impartial judge, for he judges in his own cause. His condemnation preceded his change of communion.

The nature of Guettée’s book

The editor speaks of the great learning of the author, and says “he writes with science and precision, and with the pen of a man of genius.” It may be so, but we have not discovered it. His book we have found very dull, and it has required all the effort we are capable of to read it through. To our understanding it is lacking in both science and precision. It is a book of details which are attached to no principles, and its arguments rest wholly on loose and inaccurate statements or bold assumptions.

A work more deficient in real logic, or more glaringly sophistical, it has seldom been our hard fortune to meet with. As for learning, we certainly are not learned ourselves, but the author has told us nothing that we did not know before, and nothing more than may be found in any one of our Catholic treatises on the authority of the see of Peter and the Roman pontiff.

All his objections to the papacy worth noticing may be found with their answers in The Primacy of the Apostolic See Vindicated, by the lamented Francis Patrick Kenrick, late archbishop of Baltimore, a work of modest pretensions, but of a real merit difficult to exaggerate.

Though M. Guettée’s book is far from bewildering us by its learning or overwhelming us by its logic, we yet find it no easy matter to compress an adequate reply to it within any reasonable compass.

It is not a scientific work. The author lays down no principles which he labors to establish and develop, but dwells on details, detached statements, assertions, and criticisms, which cannot be replied to separately without extending the reply some two or three times the length of the work itself, for an objection can be made in far fewer words than it takes to refute it. The author writes without method, and seems never to have dreamed of classifying his proofs, and arranging all he has to say under appropriate heads.

Indeed, he has no principles, and he adduces no proofs; he only comments on the proofs of the papacy urged by our theologians, and endeavors to prove that they do not mean what we say they do, or that they may be understood in a different sense. Hence, taking these up one after another, he is constantly saying the same things over and over again, with most tiresome repetition, which require an equally tiresome repetition in reply.

Had the author taken the time, if he had the ability, to reduce his objections to order, and to their real value, a few pages would have sufficed both to state and to refute them. As it is, we can only do the best we can within the limited space at our command.

The book’s theses

The author professes to write from the point of view of a non-united Greek, who has little quarrel with Rome, save on the single question of the papacy. He concedes in some sense the primacy of Peter, and that the bishop of Rome is the first bishop of the church, nay, that by ecclesiastical right he has the primacy of jurisdiction, though not universal jurisdiction; but denies that the Roman pontiff has the sovereignty of the universal church by divine right. He says his study of the subject has brought him to these conclusions:

“The bishop of Rome did not for eight centuries possess the authority of divine right that he has since sought to exercise”

“The pretension of the bishop of Rome to the sovereignty of divine right over the whole church was the real cause of the division,” or schism between the East and the West.” (p. 31.)

These very propositions in the original, to say nothing of the translation, show great lack of precision in the writer. He would have better expressed his own meaning if he had said: The bishop of Rome did not for eight centuries hold by divine right the authority he has since claimed, and the pretension of the bishop of Rome to the sovereignty of the whole church by divine right has been the real cause of the schism. We shall soon object to this word sovereignty, but for the moment let it pass.

These two propositions the author undertakes to prove, and he attempts to prove them by showing or asserting that the proofs which our theologians allege from the Holy Scriptures, the fathers, and the councils, do not prove the primacy claimed by the bishop of Rome.

This, if done, would be to the purpose if the question turned on admitting the claims of the Roman pontiff, but by no means when the question turns on rejecting these claims and ousting the pope from his possession. The author must go further. It is not enough to show that our evidences of title are insufficient; he must disprove the title itself, either by proving that no such title ever issued, or that it vests in an adverse claimant. This, as we shall see, he utterly fails to do. He sets up, properly speaking, no adverse claimant, and fails to prove that no such title ever issued.

The pope is in possession—especially from the Council of Florence

It suffices us, in reply, to plead possession. The pope is, and long has been, in possession by the acknowledgment of both East and West, and it is for the author to show reasons why he should be ousted, and, if those reasons do not necessarily invalidate his possessions, the pope is not obliged to show his titles. All he need reply is, Olim possideo.

That the pope is in possession of all he claims is evident not only from the fact that he has from the earliest times exercised the primacy of jurisdiction claimed for him, but from the Council of Florence held in 1439.

“We define,” say the fathers of the council, “that the holy apostolic see and the Roman pontiff hold the primacy in all the world, and that the Roman pontiff is the successor of blessed Peter, prince of the apostles and true vicar of Christ, and head of the whole church, the father and teacher of all Christians, and that to him is given in blessed Peter, by our Lord Jesus Christ, full power to feed, direct, and govern the universal church; et ipsi B. Petro pascendi, regendi, et gubernandi plenam potestatem traditam esse.”

This definition was made by the universal church, for it was subscribed by the bishops of both the East and the West, and among the bishops of the East that accepted it were the patriarchs of Constantinople and Alexandria, and the metropolitans of Russia, with those of Nicæa, Trebizond, Lacedæmon, and Mitylena.

We know very well that the non-united Greeks reject this council, although the Eastern Church was more fully represented in it than the Western Church was in that at Nicæa, the first of Constantinople, Ephesus, or Chalcedon; but it is for the non-united Greeks to prove that, in rejecting it and refusing obedience to its decrees, they are not schismatic. At any rate, the council is sufficient to prove that the pope is in possession by the judgment of both East and West, and to throw the burden of proof on those who deny the papal authority and assert that the papacy is schismatic.

Guettée’s use (and misuse) of Scripture

Before producing his proofs, the author examines the Holy Scriptures to ascertain “whether the pretensions of the bishop of Rome to a universal sovereignty of the church have, as is alleged, any ground in the word of God.” (p. 31.)

The translation here is inexact; it should be: “Whether the pretensions, etc., to the universal sovereignty of the church have, as is alleged, their foundation in the word of God.” The author himself would have expressed himself better if he had written “the sovereignty of the universal church,” instead of “universal sovereignty of the church.”

But the author mistakes the real question he has to consider. The real question for him is not whether the primacy we assert for the Roman pontiff has its ground in the written word, but whether any thing in the written word denies or contradicts it. The primacy may exist as a fact, and yet no record of it be made in the Scriptures. The constitution of the church is older than any portion of the New Testament, and it is very conceivable that, as the church must know her own constitution, it was not thought necessary to give an account of it in the written word.

The church holds the written word, but does not hold from it or under it, but from the direct and immediate appointment of Jesus Christ himself, and is inconceivable without her constitution.

Confusion over terms

The author makes another mistake, in using the word sovereignty instead of primacy.

Roman theologians assert the primacy, but not, in the ecclesiastical order, the sovereignty of the Roman pontiff. Sovereignty is a political, not an ecclesiastical term; it is, moreover, exclusive, and it is not pretended that there is no authority in the church by divine right but that of the Roman pontiff. It is not pretended that bishops are simply his vicars or deputies.

In feudal times there may have been writers who regarded him as suzerain, but we know of none that held him to be sovereign. He is indeed by some writers, chiefly French, called sovereign pontiff, but only in the sense of supreme pontiff, pontifex maximus, or summus pontifex, to indicate that he is the highest but not the exclusive authority in the church.

The Council of Florence, on which we plant ourselves, defines him to be primate, not sovereign, and ascribes to him plenary authority to feed, direct, and govern the whole church, but does not exclude other and subordinate pontiffs, who, though they receive their sees from him, yet within them govern by a divine right no less immediate than his.

The real and only sovereign of the church, in the proper sense of the term, is Jesus Christ himself. The pope is his vicar, and as much bound by his law as the humblest Christian. He is not above the law, nor is he its source, but its chief minister and supreme judge, and his legislative power is restricted to such rescripts, edicts, or canons as he judges necessary to its proper administration.

The sovereign makes the law, and the difference, therefore, between the power of the sovereign and that claimed for the Roman pontiff is very obvious and very great. Could the author, then, prove from the written word that the pope or the Holy See is not the universal sovereign of the church, he would prove nothing to his purpose. Yet this, as we shall see, is all he does prove.

The author pretends, p. 32, that the papal authority, sovereignty he means, is condemned by the word of God. The assertion, understanding the papal authority as defined by the Council of Florence, is to his purpose, if he proves it. What, then, are his proofs? The Roman theologians, that is, Catholic theologians, say the church is founded on Peter, and cite in proof the words of our Lord (St. Matt. xvi. 18): “I say unto thee that thou art Peter, and upon this rock will I build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”

But this does not prove that Peter is the rock on which the church is founded. The church is not founded on Peter, or, if on Peter, in no other sense than it is on him and the other apostles. The rock on which the church is built is Jesus Christ, who is the only foundation of the church. St. Paul says (1 Cor. iii. 11): “Other foundation can no man lay than that which is laid, which is Jesus Christ himself.”

Jesus Christ and his vicar

That Jesus Christ is the sole foundation of the church in the primary and absolute sense, nobody denies or questions, and we have asserted it in asserting that he is the real and only sovereign of the church; but this does not exclude Peter from being its foundation in a secondary and vicarial sense, the only sense asserted by the most thorough-going papists, as is evident from what St. Paul writes to the Ephesians, (ii. 20,) as cited by the author: “You are built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ being himself the chief corner-stone.” The principal, primary, absolute foundation is Christ, but the prophets and apostles are also the foundation on which the church, the mystic temple, is built. The author says, same page: “The prophets and apostles form the first layers of this mystic edifice. The faithful are raised on these foundations, and form the edifice itself; finally, Jesus Christ is the principal stone, the corner-stone, which gives solidity to the monument.”

This is very true, and we maintain, as well as he, that there is “no other foundation” in the primary sense, “no other principal corner-stone than Jesus Christ;” but he himself asserts, as does St. Paul, other “foundation” in a secondary sense. So, though our Lord is the principal or first foundation in the sense in which God is the first cause of all creatures and their acts, yet nothing hinders Peter from being a secondary foundation, as creatures may be and are what philosophers term second causes.

But in this secondary sense, “all the apostles are the foundation, and the church is no more founded on Peter than on the rest of the apostles.” Not founded on Peter to the exclusion of the other apostles certainly, but not founded on Peter as the prince of the apostles, or chief of the apostolic college, does not appear, and it is never pretended that Peter excludes the other apostles.

Our Lord gave, indeed, to Peter alone the keys of the kingdom of heaven, thereby constituting him his steward or the chief of his household; but he gave to all authority to teach all nations all things whatsoever he had commanded them, the same power of binding and loosing that he had given to Peter, and promised to be with them as well as with him all days to the consummation of the world. There is in this nothing that excludes or denies the primacy claimed for Peter, or that implies that our Lord, as the author says, merely “gave to Peter an important ministry in his church.”

Attempts to refute the truth of the papacy

The author labors to refute the argument drawn in favor of the primacy of Peter from the command of our Lord to Peter to “confirm his brethren,” and the thrice repeated command to “feed his sheep; “ but as we are not now seeking to prove the primacy, but simply repelling the arguments adduced against it, we pass it over.

He attempts to construct an argument against the primacy of Peter from the words of our Lord to his disciples, (St. Matthew xxiii, 8): “Be ye not called Rabbi; for one is your Master, and all you are brethren. And call none your father on earth; for one is your Father, who is in heaven. Neither be ye called masters; for one is your master, Christ. He that is greatest among you shall be your servant.” “Christ, therefore,” p. 48, “forbade the apostles to take, in relation to one another, the titles of master, doctor, or even father, or pope, which is the same thing.”

Why, then, does the author take the title of Abbé, which means father, or suffer his editor to give him the title of Doctor of Divinity? His non-united Greek friends also come in for his censure; for they call their simple priests papas or popes, that is, fathers; nay, if he construes the words of our Lord strictly, he must deny all ecclesiastical authority, and, indeed, all human government, and even forbid the son to call his sire father. This would prove a little too much for him as well as for us.

The key to the meaning of our Lord is not difficult to discover. He commands his disciples not to call any one master, teacher, or father, that is, not to recognize as binding on them any authority that does not come from God, and to remember that they are all brethren, and must obey God rather than men. God alone is sovereign, and we are bound to obey him, and no one else; for, in obeying our prelates whom the Holy Ghost has set over us, it is he and he only whom we obey.

He commands his disciples to suffer no man to call them masters; for their authority to teach or govern comes not from them, but from their Master who is in heaven, and therefore they are not to lord it over their brethren, but to govern only so as to serve them. “Let him that is greatest among you be your servant.” Power is not for him who governs, but for them who are governed, and he is greatest who best serves his brethren.

The pope, in reference to the admonition of our Lord, and from the humility with which all power given to men should be held and exercised, calls himself “servant of servants.” The words so understood—and they may be so understood—convey no prohibition of the authority claimed for the Roman pontiff as the vicar of Christ, and father and teacher of all Christians, by divine authority, not by his own personal right.

Here is all the author adduces from the Scriptures, that amounts to any thing, to prove “that the papal authority” is “condemned by the word of God,” and nothing in all this condemns it in the sense defined by the Council of Florence, which is all we have to show.

Guettée sets up his next move: the Fathers

From the Scriptures the author passes to tradition, and first to “the views of the papal authority taken by the fathers of the first three centuries.”

He does not deny that our Lord treated Peter with great personal consideration, and thinks Peter may be regarded in relation to the other apostles as primus inter pares, the first among equals, but without jurisdiction; and he says, p. 48, “We can affirm that no father of the church has seen in the primacy of Peter any title to jurisdiction or absolute authority in the church.”

But the first father he finds who, as he pretends, absolutely denies the primacy Catholics claim for Peter, and consequently for his successor, is St. Cyprian, who seems to us very positively to affirm it.

We will continue with Brownson’s analysis of Guettée’s misuse of St Cyprian in the next part.

Further Parts:

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further Reading

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

We have previously criticised Brownson’s unfair treatment of Cardinal Newman. Nonetheless, he wrote much of great value in defence of Christ’s Church—as this piece proves.

The Papacy: Its Historic Origin and Primitive Relations with the Eastern Churches. By the Abbé Guettée, D.D.

Translated from the French, and prefaced by an original biographical notice of the author, with an Introduction by A. Cleveland Coxe, Bishop of Western New York. New York: 1867.

The original article is available in OCR form here.