The real timeline of the Last Supper and the Crucifixion

Some say Christ celebrated the Last Supper a day early—or even that the Evangelists disagree. Fray Luis de León explains the truth.

Some say Christ celebrated the Last Supper a day early—or even that the Evangelists disagree. Fray Luis de León explains the truth.

Editor’s Note

This essay by Fray Luis is important—but it is long and theological, rather than devotional.

For a more devotional piece for Maundy Thursday, see the below:

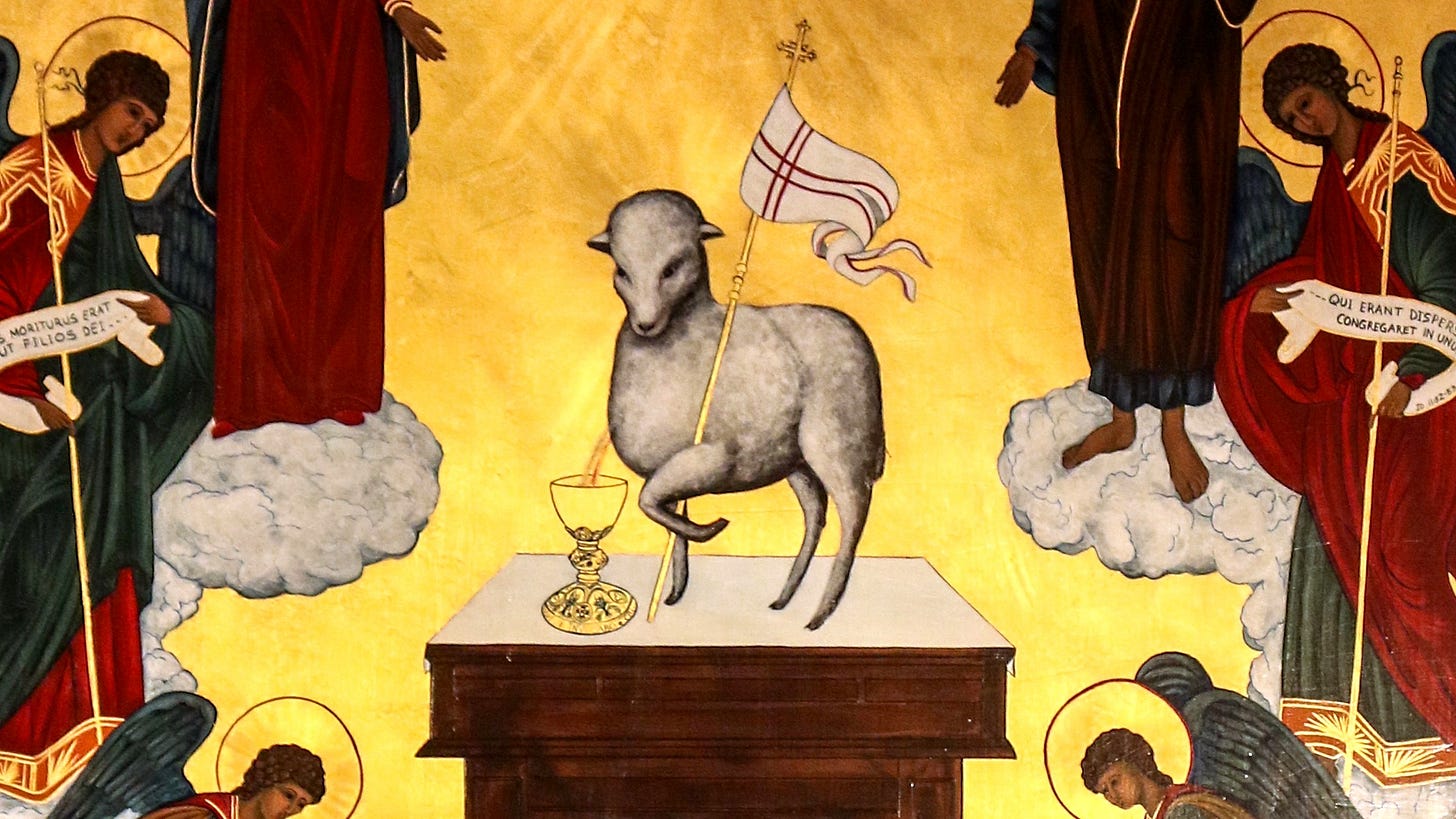

The Legitimate Time of the Immolation of Both Lambs

The Figurative and the True

On the Last Supper of Our Lord Jesus Christ

By Fray Luis de León

Preface by Fr Gabriel Daniel SJ (1695)

Disputes concerning the Pasch have become exceedingly common among the learned since the Rev. P. Lami of the Oratory proposed his new System touching the last Pasch of our Lord Jesus Christ. He has had many opponents, to whose number I do not intend to add. I should not dare to touch a matter that so many skilful men have exhausted, and if in the end I draw a conclusion contrary to the doctrine of that learned author, it is solely by means of a general argument that does not enter into the discussion of the many particular points urged against him.

The first part of this little work is nothing other than the translation of a treatise composed almost a century ago by a Spanish doctor on the occasion of the disputes then arising in Spain upon this subject. This doctor was a religious of the Augustinian Order named Luis de León, a capable theologian and a man of wit, whose style is clear, methodical, and exact. His proofs and reasonings are here the same, and in the same order, as in the original. I have only inserted a few transitions to render the discourse more fluent, and I have abridged one or two portions that seemed to me over‑long and not of equal strength with the rest.

This small treatise is found in Latin among the works of another very learned theologian of the same Order named Basilio Ponce, entitled Variae disputationes ex utraque Theologia Scholastica et Positiva (Various Disputations from both Scholastic and Positive Theology). He was a disciple of Luis de León and wrote a treatise on the same subject which is in substance no more than that of his master, upon which he enlarged at much greater length.

Should one wish in our tongue to make a corpus of all the Systems that have been proposed concerning the question of the last Pasch of our Lord, this must be added in order that it be complete; for it is wholly different from the rest, and it cannot be denied that it is ingenious.

I give no other name than that of “System” to this opinion of my Spanish doctor, and it deserves it as well as the others that have been so called, which deserve it no less. The sole point that this theologian assumes—namely, the manner in which he believes Moses understood “the night of the fourteenth of the moon”—is founded upon Scripture, yet in such wise that he does not demonstrate plainly from Scripture that this is Moses’ meaning; and therefore his opinion is no more than a “System.” Once his principle is laid down, he explains most plausibly the greatest difficulties of the subject in hand, and for that reason this opinion is a good System. These are the chief rules by which one ought to esteem more or less the various views proposed in these matters.

Besides the reflections I offer upon Fray Luis de León’s treatise on the last Pasch of our Lord, I have added [to follow in a further part] others on the discipline and usages of the Churches of Asia which, in the first centuries of Christianity, celebrated the feast of the Pasch on the fourteenth of the moon; and I have examined whether anything may be concluded from their tradition—which was a true tradition—regarding the decision of the question of our Lord’s last Pasch. I think I have treated this point of ecclesiastical history in a very particular manner and have destroyed certain prejudices as false as they are common. The reader will judge.

It appears to me that the dissertation I make may serve to confirm Fray Luis de León’s “System.” Without the relation that these two pieces bear to one another, I should not have published them; though perhaps, independent of each other, they are not unworthy to be read.

The Text of Fray Luis de León

Introduction

Moses, in chapter XXIII of Leviticus, relates that God commanded the people of Israel to immolate a Lamb on the fourteenth day of the first month [Nissan]. To this victim was given the name Pasch, a Hebrew word signifying Passage. This is because, when the Israelites were about to depart from Egypt, having placed upon the door of their houses the blood of the Lamb they had immolated, the destroying Angel passed over them all, doing them no harm.

A false preconception, by which this command of God has commonly been explained, has given rise to questions most difficult to resolve, which have cost the ablest men much labour and have rendered obscure certain passages of Scripture that are indeed very clear and easy to understand.

The error in the beginning

For, touching that which Scripture expressly notes—namely, that the Lamb was to be immolated on the fourteenth day at night—the greater part supposed that this immolation took place at the end of the fourteenth day. This is because, according to ordinary notions, the night is the close of the day. This error has caused much perplexity regarding a question proposed by the interpreters of the Gospel: On what day of the month did our Lord Jesus Christ hold the Last Supper, and on what day did he suffer death?

I have ever marvelled that so many persons learned in the sacred Letters should have fallen into this particular error, which has been the source of many—who knows how many—false systems about this matter. For it is this error that made some imagine that Jesus Christ anticipated the day of the Jews’ Pasch. Hence the Greeks are wont to assert that Jesus used leavened bread in the institution of the adorable sacrament of his Body. In a word, it is this error that has given occasion to all the chimeras that each has fashioned according to his fancy—all in order to take false steps, to the place whither his first error had previously committed him.

I say, then, that it is a very great error to believe that the night for the Hebrews was the last part of the day, as it is among us. Night was the beginning of their day; and thus it was at the opening of the fourteenth day that the lamb was to be immolated, because God’s command was that it should be immolated on the night of the fourteenth day:

In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at evening is the Lord’s Pasch (Lev. XXIII, 1).

This is what I purpose to prove in this little Treatise.

What this treatise will prove

Here, in two words, is the method I shall follow.

First, I shall show that it was in the first night of the fourteenth day of the month—that is, at the beginning of that day [according to their reckoning]—that the Israelites immolated the Lamb, when they departed from Egypt. I shall show also that Jesus Christ did the same at his last Pasch, and that he himself, who was the true Lamb, having been set upon the Cross by the Jews, offered himself that same fourteenth day of the month in sacrifice to God his Father.

Lastly, I shall explain in a very natural manner various passages of the Gospel that have hitherto seemed most difficult to understand.

But in order to prove that the lamb, which was a figure of Jesus Christ, had to be immolated on the first night—that is, at [their] beginning of the fourteenth day—it is necessary first to establish what I have said concerning the beginning of the day according to Hebrew usage.

The Hebrew day begins in the evening

The first day of the world, according to Moses’ manner of speaking, began in the evening; those that followed began in the same way, and so all the rest. Whenever he speaks of the two parts whereof the day is composed, he always names night before morning:

Et facta est vespera et factus est mane, dies unus.

And there was evening and there was morning, the first day. (Gen. I, 5);Et facta est vespera et factus est mane, dies secundus.

And there was evening and there was morning, the second day. (Gen. I, 8).

According to this rule, the day that begins at night, ends with the night following—which will be the beginning of another day. Night will be the beginning and morning the end; and when Scripture says that a sacrifice is to be made on the night of the fourteenth day, it is as though it said that it is to be offered at [their] beginning of the fourteenth day.

If there could be any doubt concerning the civil or natural day, there is and can be none concerning the festal days. All agree that those days began at night:

A véspera usque ad vesperam celebrabitis sabbata vestra.

From evening to evening shall you keep your sabbaths. (Lev. XXIII, 32).

Now although the fourteenth day was not properly a feast—that is, work was not forbidden upon it—nevertheless it was a day that was celebrated and solemnised on account of the immolation of the Paschal Lamb, the eating of the Unleavened Bread at the banquet in which the Lamb was consumed, and the other preparations made for the Pasch—which was the next day, and began with the second night [by our reckoning] of that same day; thus [the fourteenth day] must be reckoned among the number of the solemn days that began with a night. But I shall bring forward more particular proofs of what I say.

The Last Supper was on the first day of unleavened bread

I assume, according to the almost universal sentiment of all the faithful, of all the Fathers, and of all the theologians, that our Lord Jesus Christ kept the Pasch with the ordinary ceremonies on the night preceding his death. What I ask is whether he kept it on the day appointed by the Law or anticipated the day, as the Greeks and some Catholic Doctors maintain. The authority of the Gospels is so express in shewing that he did not anticipate it that, without entering further into the matter, I think I have the right for a moment to suppose that opinion true by virtue of the very words of the three Evangelists:

Prima autem die azymorum accesserunt discipuli ad Iesum, dicentes ei: Ubi vis paremus tibi comedere pascha?

On the first day of Unleavened Bread the disciples came to Jesus and said, “Where wilt thou that we prepare for thee to eat the Pasch?” (Mt. XXVI, 17);Et primo die azymorum, quando pascha immolabant, dicunt ei discipuli eius, &c.

And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when the Pasch was being immolated, his disciples said to him, &c. (Mk. XIV, 12);Venit autem dies azymorum, in qua necesse erat occidi pascha, &c.

Now came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Pasch had to be slain, &c. (Lk. XXII, 7).

Can these words be read without perceiving that that day was the first day of Unleavened Bread in Jerusalem, the very day on which the Jews immolated, and were bound to immolate, the Pasch?

The Last Supper was at the beginning of the Hebrews’ fourteenth day

Upon these words, as explicit as any, I suppose that our Lord Jesus Christ did not anticipate the day marked by the Law for the Pasch. But, upon this supposition, I maintain that, having celebrated the Pasch on the fourteenth day of the month, he kept it on the night which was the beginning of that fourteenth day [by their reckoning—so, “the thirteenth day” by ours]. For if he did not keep it on the night which was the beginning of [their] fourteenth, he kept it the following night—that is, at [their] beginning of the fifteenth; and as he was seized by the Jews a few hours later and crucified the next morning, it would follow that he was arrested, brought before the tribunal of the Roman governor, condemned, scourged, crucified and buried on the fifteenth day of the month.

This is an assertion that cannot be maintained upon any grounds, and for these reasons:

First, the fifteenth was the feast day of the Pasch, the most celebrated of the feasts; but judicial proceedings and trials were forbidden among the Jews on feast days, as also the burial of the dead, and especially on this day:

Omne opus servile non facietis

Ye shall do no servile work therein (Lev. XXIII, 7).

Secondly, according to St John, the day on which our Lord Jesus Christ was crucified was parasceve paschae (the preparation of the Pasch) (Jn. XIX, 14), that is, according to the meaning of the word parasceve, the day on which they prepared for the feast of the Pasch. That day, then, was not the feast itself of the Pasch, and therefore it was not the fifteenth day of the month.

Therefore it is certain that our Lord kept the Pasch on the first night of the fourteenth day [by their reckoning]; and if he kept it, then, at the time ordained by the Law, as the three Evangelists affirm, it follows that the time for immolating the Lamb on the fourteenth was the beginning and not the end of that [fourteenth] day.

The timing of the first Passover—Josephus

Yet one might wonder whether the Lamb was not immolated at the very hour at which the Hebrews immolated it when they were about to depart from Egypt, since this ceremony was instituted solely to represent that circumstance itself and that the Israelites might recall it every year. Let us then examine this point, and we shall see clearly that the Hebrews at that time immolated the Lamb on the night which was the beginning of the fourteenth day.

This is what Josephus teaches us, whose authority carries great weight in this matter. Thus he says in Book II, chap. V of the Antiquities of the Jews:

“God, having declared that with one more plague he would compel the Egyptians to let the Hebrews depart, bade Moses tell the people to have a sacrifice ready, preparing on the tenth day of the month Xanthicus, for the fourteenth day—the month which the Egyptians call Pharmuthi, the Hebrews Nissan, and the Macedonians Xanthicus—and that he himself should lead the Hebrews forth with all their possessions.

“Moses, having assembled them in one place, divided them by families and held them in readiness for the march. And when the fourteenth day had arrived, (ἐνστάσης δὲ τῆς τεσσαρεσκαιδεκάτης), they all offered the sacrifice in order to depart, and with the blood of the Lamb they purified their houses by means of hyssop. After supper they burnt what remained of the flesh of the Lamb, as being ready to set out; hence the custom of performing this immolation every year. The feast is called Pascha.”

Can one state more expressly than Josephus that the immolation is performed at the beginning of the fourteenth day?

Yet we have, besides, another witness to this fact far less open to objection than Josephus: it is the sacred writer Moses himself, of whom I shall cite certain passages which will lead us, as by degrees, to the knowledge of the truth.

The timing of the first Passover—Moses

First, it is firmly established in the Sacred Scriptures that the Hebrews, when leaving Egypt, set out from Rameses, the city in which—and in the country round about—it had been ordered by Moses that all should assemble, and from which they all departed together, urged on by the Egyptians that they might be gone as soon as possible.

And the children of Israel set forward from Ramesse to Socoth, being about six hundred thousand men on foot, beside children.

And a mixed multitude, without number, went up also with them, sheep and herds, and beasts of divers kinds, exceeding many. (Ex. XII, 37‑38).

It is likewise certain from Scripture that the Israelites made their first march by night and that they departed from Rameses at sunset.

This is the observable night of the Lord, when he brought them forth out of the land of Egypt: this night all the children of Israel must observe in their generations. (Ex. XII, 42).

And in Deuteronomy, chap. XVI:

Observe the month of new corn, which is the first of the spring, that thou mayst celebrate the phase to the Lord thy God: because in this month the Lord thy God brought thee out of Egypt by night.

And thou shalt sacrifice the phase to the Lord thy God, of sheep, and of oxen, in the place which the Lord thy God shall choose, that his name may dwell there.

Thou shalt not eat with it leavened bread: seven days shalt thou eat without leaven, the bread of affliction, because thou camest out of Egypt in fear: that thou mayst remember the day of thy coming out of Egypt, all the days of thy life.

No leaven shall be seen in all thy coasts for seven days, neither shall any of the flesh of that which was sacrificed the first day in the evening remain until morning.

Thou mayst not immolate the phase in any one of thy cities, which the Lord thy God will give thee: But in the place which the Lord thy God shall choose, that his name may dwell there: thou shalt immolate the phase in the evening, at the going down of the sun, at which time thou camest out of Egypt.

And thou shalt dress, and eat it in the place which the Lord thy God shall choose, and in the morning rising up thou shalt go into thy dwellings. (vv. 1‑7).

Two sacrifices called ‘Phase’ or ‘Pasch’

It must be noted, concerning the word Phase or Pasch at the end of this citation, that this Phase—the victim God commanded to be immolated ad solis occasum [at the going down of the sun] at the hour when the Hebrews left Egypt—is not the Lamb that was also called Phase or Pasch and had to be immolated on the fourteenth of the month at night, but another victim of an eucharistic or thanksgiving sacrifice in memory of their passage from slavery to liberty; and for this reason it too was called Phase or Pasch, that is, Passage. They were likewise to offer this sacrifice every year, at the same time as they renewed their freedom. I shall shortly show, in the Book of Numbers, the law that prescribes it. Meanwhile let us reason a little upon these passages I have just gathered.

According to those texts of Scripture, it is certain that the Hebrews left Rameses at the beginning of the night, at sunset: ad solis occasum [at the setting of the sun] (Deut. XVI, 7). It is certain that they departed from that city on the fifteenth day of the first month, which is expressly stated in Num. XXXIII:

Now the children of Israel departed from Ramesses the first month, on the fifteenth day of the first month, the day after the phase, with a mighty hand, in the sight of all the Egyptians (v. 3).

Upon this I reason as follows:

When Scripture says that the Hebrews left Rameses on the fifteenth of the first month, it cannot be understood of the morning of the fifteenth, for it is written in Deuteronomy (XVI, 6) that they departed at sunset:

[T]hou shalt immolate the phase in the evening, at the going down of the sun, at which time thou camest out of Egypt.

Nor can it be said that they set out at sunset or during the night that follows the morning of the fifteenth, because that night would be [for them] the beginning of the sixteenth, and Scripture in that case would have said that they departed after the fifteenth, or at the beginning of the sixteenth. It remains, then, to say that they departed on the “first” night of the fifteenth and at the sunset which marked [for them] the beginning of the fifteenth.

This proposition must be kept in mind.

The Hebrews did not leave on the night the Angel slew the firstborn

Lastly, it is clearly seen from the same Scriptures, when they are studied attentively, that the Hebrews did not leave Egypt on the same night on which each one immolated the Lamb in his house; for that immolation was made very late, and it was only at midnight that the destroying Angel slew the first‑born of the houses whose doors were not stained with the Lamb’s blood:

And it came to pass at midnight, the Lord slew every firstborn in the land of Egypt. (Ex. XII, 29).

Fear then spread everywhere, and the cry of all the people rose at the sight of that universal massacre. Pharaoh therefore sent for Moses and Aaron and granted them all they had previously demanded; the rest of the night passed thus.

Furthermore, the Israelites had an express order from Moses not to set foot outside their houses until morning:

[L]et none of you go out of the door of his house till morning. (Ex. XII, 22).

From all this it follows that the Hebrews immolated the Lamb on the “first” night of the fourteenth— that is, at the beginning of that day, which began at night [on what we would call the thirteenth].

Since the Hebrews did not leave on the night when they immolated the Paschal Lamb, but only the next day at sunset or at the beginning of the following night—"the day after the phase” (Num. XXXIII, 3)—which was [their] beginning of the fifteenth day, as I have shown, it follows that the time at which they immolated the Lamb—namely twenty‑four hours earlier—was the beginning of the fourteenth day [by their reckoning].

It is certain that the Hebrews immolated the Lamb by night, which was [for them] the beginning of the fourteenth day, and not the end:

The first month, the fourteenth day of the month at evening, is the phase of the Lord. (Lev. XXIII, 5).

To make the matter more intelligible, I shall summarise in a few words the whole of this history according to the principles I have established and the proofs I have adduced.

Summary of what happened in Egypt

When Moses planned to lead the Hebrews out of Egypt as soon as possible, he ordered that the father of the family, at the head of all in the house, should immolate a lamb at the beginning of the fourteenth day, which began at night [on our thirteenth day].

He ordered that all should eat it with the ceremonies he prescribed: namely, that they should eat it standing, staffs in hand, equipped as travellers ready to set out, that they should eat it with bitter herbs and unleavened bread.

He further ordered them to stain their door‑posts with the lamb’s blood and to remain shut up in their houses, because at midnight the Angel of the Lord would pass to slay the first‑born in every house whose doors were not stained with the lamb’s blood—which indeed took place at midnight.

The Egyptians, terrified by so dreadful a calamity, clearly seeing that God was punishing them for having ill‑treated and detained the Hebrews, not only allowed them but even begged them to leave Egypt forthwith.

Thus the Jews, leaving all the villages of the land of Goshen where they dwelt, came together at Rameses in order to depart all at once.

The whole day was not long enough for this. Six hundred thousand men, not counting women and children, the flocks and the baggage they carried, could not be gathered in a moment; and it was only at night, when the fifteenth of the month began [by their reckoning], that they went forth from Rameses in battle array.

God commanded two sacrifices

But, in order that so memorable a remembrance should be perpetual, God ordained that every year, on the night of the fourteenth of the moon, the Hebrews should immolate a Lamb, and that they should eat it with the ceremonies I have enumerated, in testimony that the blood of the Lamb had preserved their houses from the sword of the destroying Angel.

Besides this, God willed that at the beginning of the fifteenth day they should sacrifice each year bullocks, one ram, and seven lambs in memory of the day on which they had been delivered from slavery by leaving Egypt, and, moreover, that on the six days following the same sacrifice should be repeated; that throughout the seven days they should abstain from eating leavened bread. All those days were called “days of the Pasch”, and two of them—namely the first, which was the fifteenth, and the last, which was the twenty‑first—were to be feast‑days.

This command is set forth at length in the Book of Numbers in these words:

And in the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, shall be the phase of the Lord,

And on the fifteenth day the solemn feast: seven days shall they eat unleavened bread.

And the first day of them shall be venerable and holy: you shall not do any servile work therein. And you shall offer a burnt sacrifice a holocaust to the Lord, two calves of the herd, one ram, seven lambs of a year old, without blemish: And for the sacrifice of every one three tenths of flour which shall be tempered with oil to every calf, and two tenths to every ram, and the tenth of a tenth, to every lamb, that is to say, to all the seven lambs:

And one buck goat for sin, to make atonement for you, besides the morning holocaust which you shall always offer.

So shall you do every day of the seven days for the food of the fire, and for a most sweet odour to the Lord, which shall rise from the holocaust, and from the libations of each.

The seventh day also shall be most solemn and holy unto you, you shall do no servile work therein. (Num. XXVIII, 16‑25).

Observation on seven days of unleavened bread

An observation must be made upon the words seven days shall they eat unleavened bread: that is to say, throughout those seven days nothing but unleavened bread was to be served at their meals, so that the whole seven were perfectly Azymes; herein they differ from the fourteenth day that immediately preceded them. For, although the Israelites were commanded to use unleavened bread when they ate the Paschal Lamb, there was nevertheless no law forbidding them to eat leavened bread on that day at other meals.

Hence it is easy to understand that there were more days of Azymes than of Pasch. For one may reckon eight days of Azymes, beginning with [their] commencement of the fourteenth, on which the Lamb was immolated, up to and including the twenty‑first; yet there were properly only seven days of Pasch, for the solemn feast of Pasch did not begin until the fifteenth, which was counted as the first day of that solemnity.

This accords with the testimony of Josephus who, as a Jew and a man thoroughly versed in Hebrew law, could not be ignorant of their usages and discipline:

“In memory of that time of want, we keep for eight days the feast known as the Azymes.” (Antiquities, Book II, chap. V).

Once the error is dispelled, the truth appears clearly

From all that has been said it seems easy to conclude that it is an error to place at the end of the fourteenth day the immolation of the Lamb prescribed by the Law. But once this error is dispelled, the truth appears clearly, and several Gospel passages that have hitherto seemed so obscure become plain and easy to understand; and this, indeed, is the best proof of the soundness of this System.

For, because St John writes that our Lord kept the Pasch with his disciples and immolated the Lamb πρὸ τῆς ἑορτῆς τοῦ πάσχα (before the feast of Pasch) (Jn. XIII, 1), many imagined that he celebrated the Pasch one day earlier than the time prescribed by the Law, confusing the immolation of the Lamb with the feast of Pasch, which are two very different things. For the feast of Pasch was the fifteenth, whereas the Lamb was immolated and eaten on the fourteenth:

And in the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, shall be the phase of the Lord;

And on the fifteenth day the solemn feast: seven days shall they eat unleavened bread. (Num. XXVIII, 16‑17).

Thus what St John says accords perfectly with what the other three Evangelists report. Jesus Christ held the Paschal banquet before the feast of Pasch according to St John, and he held it also on the first day of the Azymes, when the Pasch had to be immolated (Mk. XIV, 12; Lk. XXII, 7); both statements are entirely true, since the first day that bore the name Azymes—at the beginning of which the Hebrews ate the Lamb—was the fourteenth of the month, in the manner I have explained, and it immediately preceded the feast of Pasch celebrated on the fifteenth.

The immolation of the Lamb commanded by the Law preceded by a full day the sacrifice of bullocks that was offered the following night, that is, at the beginning of the fifteenth, the feast of the Pasch, according to these express words of Deuteronomy:

[T]hou shalt immolate the phase in the evening, at the going down of the sun, at which time thou camest out of Egypt. (Deut. XVI, 6).

But it was not on the fourteenth that the Hebrews left Egypt; it was on the fifteenth, twenty‑four hours after the immolation of the Lamb: “the day after the phase” (Num. XXXIII, 3).

Therefore the sacrifice offered on the fifteenth was likewise called phase or Pasch. This reflection upon the name of that second sacrifice is of infinite importance for the understanding of another passage of St John, which has always seemed one of the most difficult to reconcile with the other Evangelists.

This resolves confusions in St John’s Gospel

St John writes that the Pharisees and the Chief Priests, when they were bringing Jesus before Pilate, were unwilling to enter the Prætorium, lest they should contract a legal uncleanness that would prevent them from eating the Pasch, ut non contaminarentur, sed manducarent pascha (“that they might not be defiled, but might eat the Pasch”) (Jn. XVIII, 28); whence many concluded that the Jews must that day have held the banquet of the Paschal Lamb, and therefore that our Lord had anticipated by one day the time of the legal Pasch.

But that was not the case: they had kept the legal Supper the night before, which was [their] beginning of the fourteenth day; and the Pasch for which they wished to be in a state to eat consisted of the flesh of the sacrifices offered on the night that commenced the fifteenth day—the time at which the Israelites went forth from Egypt, and which Moses, in Deuteronomy XVI, calls by the name “the Pasch”:

Immolabis pascha ad vesperam, ad solis occasum, eo tempore quo egressus es de Aegypto

“Thou shalt sacrifice the pasch at eventide, at the going down of the sun, at the hour when thou camest forth from Egypt” (Deut. XVI, 6).

This circumstance, I say, clearly marks that this Pasch was not the Paschal Lamb.

Granted the truth of all this doctrine, nothing now obliges us to say—against the explicit testimony of the three Evangelists—that our Lord kept the legal Pasch a day earlier than the Jews. Such a transposition has always seemed forced in this matter. By this solution, one removes from the Jews every occasion of calumniating the Gospels for appearing to say that our Lord was crucified on the feast‑day of Pasch—that is, on the fifteenth of the month; for they mock and deride us for persuading ourselves that their Priests and High Priests could have tried Jesus, condemned him, and caused him to die on the feast‑day of Pasch—not only because such a thing was forbidden on that day, but also because Jesus died on a Friday, and they always took care that the feast of Pasch should never fall on a Friday, using an intercalary day [a day inserted into the calendar] for that very purpose, as their calendar shows.

But, I say, this calumny has no place in our system; for the Evangelists do not say that our Lord was set upon the cross on the fifteenth of the month, but that, having kept the legal supper on the first day of the Azymes and before the feast of Pasch, he was condemned the following morning and crucified. Yet that morning was still the fourteenth day, which was not the feast, and not the fifteenth, when the feast of Pasch began; so that the true Lamb and the figure of him were immolated on the self‑same fourteenth day: the figure at the beginning of the fourteenth (that is, at night) and the true Lamb eighteen hours later, about the sixth hour—that is, in our reckoning, about noon.

Thus things had to fall out, that the figure might correspond to the reality and the shadow to the substance— which does not happen in the opinion of those who say that Jesus anticipated the time of the legal Pasch, nor in that of those who maintain that he died on the fifteenth of the month.

Objections to be Resolved

It now remains to resolve certain difficulties that may be urged against my view, of which the two following are the principal.

First Objection

“It is not certain, first, that the Hebrews set out from Rameses at sunset; and, in the passage of Deuteronomy that I have cited, it is the Pasch or sacrifice of the lamb that is spoken of as performed toward sunset.”

Answer

What I have said upon these two points is sufficient to show the weakness of this objection. The text is clear as to the time of the departure from Egypt:

Immolabis pascha ad solis occasum, eo tempore quo egressus es de Aegypto.

“Thou shalt sacrifice the Pasch at the going down of the sun, at the hour when thou camest forth from Egypt” (Deut. XVI, 6).

Because Moses says that a victim which he calls Pascha shall be immolated, one must not conclude that the Israelites did not leave at sunset—for the text above is explicit—but rather, from this formal passage alone, and still more when it is joined to those of Exodus and Numbers that I have cited, one must conclude that the name Pasch is given to a sacrifice different from that of the Paschal Lamb.

This consequence is indubitable, since the victim in question was immolated on the fifteenth day, at the moment when the Jews set out from Rameses, and therefore one day after the immolation of the Lamb. Thus, in this very chapter, one sees the difference between the two sacrifices that bear the name Pasch.

The victim immolated on the fourteenth, and more commonly called Pasch, was a lamb or a kid; the other consisted of bullocks, sheep, etc.:

Immolabis in pascha victimas ovium et boum Domino Deo tuo.

“Thou shalt sacrifice at the Pasch, victims of sheep and oxen to the Lord thy God” (Deut. XVI, 2).

Second Objection

The other objection is somewhat specious and is drawn from Exodus XII, where it is said:

The first month, the fourteenth day of the month, in the evening, you shall eat unleavened bread, until the one and twentieth day of the same month, in the evening.

Seven days there shall not be found any leaven in your houses (vv. 18‑19).

It will be urged that, if one counts those seven days from the first night of the fourteenth—when I maintain that the lamb was eaten—they will end with the first night of the twenty‑first, and so the twenty‑first would not be included among the Paschal days and would not be a feast‑day. But this is false and contrary to what is laid down in Leviticus, where the seventh day is reckoned from the fifteenth and, consequently, the twenty‑first is a feast‑day that closes the Paschal solemnity.

Therefore, one must count the seven days from the second night of the fourteenth [viz., what the Hebrews would say was the fifteenth], and must accordingly place the eating of the lamb there, for it is by that act that the Days of Unleavened Bread begins.

Answer

I reply that my opinion is just as apt for reconciling, on this point, the diverse modes of speech in the Old Testament Scriptures as I have shown it to be for reconciling St John with the other three Evangelists.

Moses enjoined in Exodus that unleavened bread should be eaten for seven days and that from the first day no leaven should be found in their houses:

Seven days shall you eat unleavened bread: in the first day there shall be no leaven in your houses (Ex. XII, 15)

And he adds that the first and the last of those days should be feast‑days:

The first day shall be holy and solemn, and the seventh day shall be kept with the like solemnity: you shall do no work in them, except those things that belong to eating. (v. 16).

A few lines later he further says:

The first month, the fourteenth day of the month, in the evening, you shall eat unleavened bread, until the one and twentieth day of the same month, in the evening. (v. 18).

I say, then, first, that the seven days of the Azymes are to be reckoned from the “second” night of the fourteenth, which was the beginning of [their] fifteenth; thus the last night of the twenty‑first is included.

And at the same time I remark that this confirms my system. For in Num. XXVIII Moses distinguishes the fourteenth day—on which the Paschal Lamb was eaten and which was not a feast day—from the fifteenth day, which was a feast day.

And in the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, shall be the phase of the Lord,

And on the fifteenth day the solemn feast: seven days shall they eat unleavened bread. (vv. 16‑17).

But the “second” night of the fourteenth was itself a feast‑day, because it was the beginning of the fifteenth; therefore the night of the fourteenth, when the Paschal victim was eaten—and which differed from the fifteenth, in that it was not a feast—was not the “second” night but the “first”—and this is exactly my opinion.

Secondly, I add that the beginning of the Azymes can be understood of the “first” night of the fourteenth, the date on which I maintain that the Paschal Lamb was eaten; and it is so taken by the first three Evangelists—St Matthew, St Mark, and St Luke:

“On the first day of Unleavened Bread the disciples came to Jesus and said, ‘Where wilt thou that we prepare for thee to eat the Pasch?’” (Mt. XXVI, 17);

“And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when the Pasch was being immolated, his disciples said to him, etc.” (Mk. XIV, 12);

“Now came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Pasch had to be slain, etc.” (Lk. XXII, 7).

The reason why that day was called “the first day of Unleavened Bread” is that unleavened bread began to be eaten from then onward, namely, from the banquet of the Paschal Lamb:

And they shall eat the flesh that night roasted at the fire, and unleavened bread with wild lettuce. (Ex. XII, 8).

This did not hinder their using leavened bread at other meals; for the prohibition of having leaven in the house obtained only for the seven days properly called the days of the Azymes, according to the Law:

Seven days there shall not be found any leaven in your houses. (Ex. XII, 19).

And that designation extended to the fourteenth day only by custom, founded on the fact that unleavened bread was served from that day at the banquet of the Paschal Lamb.

Related Objection

Thus, it might be objected again, there would be eight days of Azymes.

Answer

I answer that, according to the words of the Law and speaking strictly, there were only seven; but according to the ordinary manner of speech, founded on what I have just said, there were eight—and this is no conjecture adopted through necessity to sustain my System, but that I take it from Josephus himself. Josephus, including in the feast of Pasch all the ceremonies connected with it and representing to the Israelites every circumstance of their deliverance from Egyptian bondage, expressly counts eight days:

“In memory of that time of want, we keep for eight days the feast known as the Azymes.” (Antiquities, Book II, chap. V).

Fr Ruppert (for example), without taking account of Josephus’ testimony, concluded from the Exodus passage I have cited several times that there were eight days of Azymes; for, says he, Moses counts the first day and, besides, yet seven days of Azymes:

The first month, the fourteenth day of the month, in the evening, you shall eat unleavened bread, until the one and twentieth day of the same month, in the evening. (Ex. XII, 18).

Thus, without forcing anything, the Old and the New Testament coincide perfectly in my system.

Editor’s Postscript

In a later part, we will see Fr Gabriel Daniel’s reflections on this system, and how the practice of the Quartodecimans strikingly confirms it.

Incidentally, we could note that parts of Fray Luis’ observations are confirmed by the practice of Jewish groups today, who celebrate not one but two seder meals, treating 14 Nissan as Erev Pesach (“Eve of Passover”) and the day for the first seder, and 15 Nissan as the first day of Passover proper, and the day for the second seder—although it is not always easy to follow their systems of dating.

Read Next:

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Based text of translation made with the assistance of AI and each line scrutinised and checked against the French text.

Curious, but does this also help explain "on the third day He rose again"? If we use the timeline as outlined in the article, then indeed the Resurrection is on the third day. If however we go by the sunrise idea of day, it only seems to me to be two days, having already risen by sunrise on the second day.