“That Golden Book”: On the Roman Catechism, and a review of Baronius Press’s edition

This essay consists of two parts:

Part I – Review of Baronius Press’s edition of the Roman Catechism

Part II – The Roman Catechism itself

Historical background

The authority of the Roman Catechism

Clergy and theologians on the Catechism

Comparison with the modern catechism

The Roman Catechism and the crisis in the Church

The nature and structure of this Catechism.

Supporting The WM Review through book purchases

As Amazon Associates, we earn from qualifying purchases through our Amazon links. Click here for The WM Review Reading List (with direct links for US and UK readers).

The Catechism of the Council of Trent – also known as the Catechism of St Pius V, or the Catechism for Parish Priests – is more familiarly known as, the Roman Catechism.

It would be a strange idea to “review” the Roman Catechism in itself. Naturally we do not sit in judgment on this text: rather, it is a rule by which we ourselves are judged.

Nonetheless there are different editions of the text available, so I thought it worthwhile to review the version by Baronius Press, whilst giving some background to the text itself.

(As an Amazon Associate, the WM Review will earn a commission from qualifying purchases bought through this and other such links.)

The Baronius Press leatherbound hardback version is an update from their previous paperback. Their previous version featured a different translation, but this version switches to the text of two Dominicans, John A. McHugh and Charles J. Callan. These two Dominicans are also the authors of the popular two-volume Moral Theology, subtitled A complete course based on St Thomas Aquinas and the best modern authorities.

This was a good move for Baronius, as their text is considerably more readable and well-formatted than the previous. The greater sign-posting of topics increases the ease of use for readers.[1]

I will start reviewing the beautiful physical book itself, and then discuss the Roman Catechism’s history, the approvals it has received, its importance in the post-conciliar period, and the nature of its content.

Part I

Review of Baronius Press’s edition

Without a doubt, the Baronius Press edition is the best available. There are other hardbacks or cheap facsimile paperback copies around, either with the McHugh and Callan text or with others. But the Baronius edition is, for me, the best version.

Baronius Press have long taken great care in their books as physical products – and this has only increased with recent publications such as this. As such, they have some very “high spec” items.

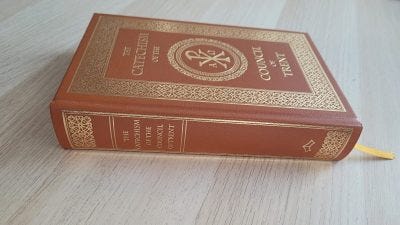

As is clear from the pictures, the book is beautiful. The gold foil on the orange leather hardback looks the part. The binding is very fine, along with the lovely Baronius endpapers, ribbons and head and tail bands. The book itself is a good size, fitting well into one’s hands and being the right sort of weight. The paper is high-quality and the fonts are very easy to read, especially compared to other options on the market.

The book – like their others – is “smyth-sewn,” which means that the text-block has been sewn together in a particular way before it has been completed. Groups of folded pages are stitched together, and these are in turn sewn together to form the book. By contrast, the most common means of binding books these days is with glue.

The glue used by many self-publishing companies today seems to be of better quality than the type many mainstream publishers used to use, such that spines generally stay intact without creasing: but nothing beats a properly smyth-sewn book. Such books open naturally and lie flat, unlike those which just use glue. This makes a very great difference when it comes to reading, and even more for study and writing.

The footnotes are interesting in this book, as several have their numbers underlined. At first I thought that this was a mistake, but it actually denotes those inserted by McHugh and Callan themselves, usually with references to the Summa Theologica. This is an interesting feature to have.

For the clergy, the McHugh and Callan version includes a fully referenced Sermon Programme following the traditional Roman calendar. For each Sunday and Holy Day a “dogmatic subject” and “moral subject” is given, along with multiple references to the text. This is useful for meditation for all Christians too. It also includes a comprehensive index.

All of these factors come together to make a book that is built to last. Baronius Press’s Roman Catechism is a book which will remain in good condition for several generations to come. The same cannot be said for many books on the market these days.

So much for the physical book. But what of the text itself? What role has it played in the life of the Catholic Church?

Part II

The Roman Catechism itself

Background

McHugh and Callan’s introduction contains an excellent summary of the Roman Catechism’s qualities.

This introduction tells us that the idea of publishing an official, universal catechism was raised at the Council of Trent in April 1546. Initially, the decree proposed such a thing for children and uninstructed adults, “‘who are in need of milk rather than solid food.’”[2] Although the Council fathers approved, nothing appears to have happened until sixteen years later, when St Charles Borromeo apparently brought up the question again. In response, the Council appointed a commission to carry out this project.

At the start of 1563, the papal legates announced that the committee had begun its work. The committee recruited a wide range of theologians from different nations and orders, and each of the articles of the Creed and so on were divided amongst them. But despite the presence of representatives from different schools of theology, the Roman Catechism limited itself as far as possible to a universal and comprehensive presentation of the Catholic Faith. As McHugh and Callan put it:

“All those who had part in the work of the Catechism were instructed to avoid in its composition the particular opinions of individuals and schools, and to express the doctrine of the universal Church, keeping especially in mind the decrees of the Council of Trent.”[3]

In September 1563, the commission reported back to the Council on its progress. The subsequent discussions led to a change in direction – instead of something like the later Penny Catechism, it was decided that the commission was to prepare “a much more extensive and more thorough work to be used by parish priests in the instruction of the faithful.”[4] Soon after this, the Council decreed that the text was to be translated into the various vernaculars “and expounded to the people by all parish priests.”[5]

The work was not finished by the time that the Council of Trent was closed. The Roman Pontiff took charge of it, and appointed St Charles Borromeo as the president of the committee when the previous one died. St Charles recruited “the greatest masters of the Latin tongue of that age” to ensure the quality of the style, and it was revised several times from this perspective.[6] When St Pius V acceded to the papacy in 1566, he appointed several “expert theological revisers” whose task it was “to examine every statement in the Catechism from the viewpoint of doctrine.”[7]

By the end of the year it was completed, and then published.

The authority of the Roman Catechism

McHugh and Callan write that the Roman Catechism “is unlike any other summary of Christian doctrine” because “it enjoys a unique authority among manuals.”[8] Let’s survey the distinguishing qualities of this Catechism.

It was created by the express command of the Council of Trent, which also commanded that it be translated into the various vernacular languages and used as a touchstone for preaching.

It comes with the approval of very many Roman Pontiffs. It was begun by Pius IV, completed, published and repeatedly commended by St Pius V, and praised in the highest terms by their successors. For example, in 1761 Clement XII said that no other catechism could be compared with it, and that “the Roman Pontiffs offered this work to pastors as a norm of Catholic teaching and discipline so that there might be uniformity and harmony in the instructions of all.”[9]

In 1899 Leo XIII taught that all seminarians should possess and constantly study two books: the Summa Theologica of St Thomas Aquinas and this Roman Catechism, which he called “that golden book.”[10] He wrote of it:

“This work is remarkable at once for the richness and exactness of its doctrine, and for the elegance of its style; it is a precious summary of all theology, both dogmatic and moral. He who understands it well, will have always at his service those aids by which a priest is enabled to preach with fruit, to acquit himself worthily of the important ministry of the confessional and of the direction of souls, and will be in a position to refute the objections of unbelievers.”[11]

In 1905, St Pius X wrote that both adults and children needed religious instruction, and required that the basis for this instruction be the Roman Catechism.

In addition to the popes, various local councils made the use of the Roman Catechism obligatory following its publication. St Charles Borromeo ordered that it be studied in seminaries and used throughout his diocese.

McHugh and Callan summarise it thus:

“In short, synods repeatedly prescribed that the clergy should make such frequent use of the Catechism as not only to be thoroughly familiar with its contents, but almost have it by heart.”[12]

Clergy and Theologians on the Roman Catechism

Cardinal Valerius – a friend of St Charles Borromeo – wrote the following:

“This work contains all that is needful for the instruction of the faithful; and it is written with such order, clearness and majesty that through it we seem to hear holy Mother the Church herself, taught by the Holy Ghost, speaking to us…. It was composed by order of the Fathers of Trent under the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, and was published by the authority of the Vicar of Christ.”[13]

The Salmanticenses – the famous Carmelite commentators on the works of Aquinas – said that “the authority of this Catechism has always been of the greatest in the Church.”[14] The reasons they give are: its origin in a command of Trent; the very high learning of its authors; the severe scrutiny given it by St Pius V and Gregory XIII; and the commendation by “nearly all the [local] Councils” held since Trent.

Cardinal Newman wrote in his Apologia: “I rarely preach a sermon but I go to this beautiful and complete Catechism to get both my matter and my doctrine.”[15]

Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton explains the magisterial nature of this catechism. Diocesan catechisms, he writes, are exercises of the bishops’ ordinary magisterium:

“Catechisms and other approved books of Christian doctrine, in so far as they are adopted by the ordinaries of the various dioceses for teaching the content of the faith to the people of these dioceses, may be said to express the ordinary magisterium of the Catholic Church.”[16]

Further, it is an accepted opinion that points of doctrine that appear in the moral universality of catechisms constitute an exercise of the Church’s infallible universal ordinary magisterium:

“The unanimous teaching of these catechisms can rightly be considered by the theologians as an indication of the ordinary and universal magisterium of the Catholic Church. The doctrine that is universally or unanimously proposed in these doctrinal books, in such a way that it is presented to practically all of the Catholics of the world as revealed truth, is certainly a verity taught and exposed infallibly in the ordinary and universal magisterium of the Catholic Church.”[17]

As such, these points of doctrine are sure, safe, and true – and if they are taught as divinely revealed, they are to be believed with divine and Catholic faith.

Is the Roman Catechism one such text amongst others? Naturally, not all catechisms are equal. A diocesan catechism carries a different weight to one adopted by a whole nation, or more importantly the universal Church. Fenton continues:

“Some of them have had a very restricted use. Others, like the old standard Baltimore Catechism in our own country, have really been important factors in teaching the faith to Catholics of an entire nation. Others again, like the Roman Catechism […] have had world-wide popularity and use.”[18]

J.M.A. Vacant, in talking about the authority of catechisms, singles out the Roman Catechism:

“The catechism of the Council of Trent and the diocesan catechisms, considered as a whole, express the doctrine of the Supreme Pontiffs and the bishops who had them drawn up; at the same time, they manifest the belief of the faithful, since they are the immediate rule.

“As these catechisms are intended to set forth not what is opinion, but what is the faith of all, most of the points which they agree to teach without restriction must be regarded as proposed to our faith.”[19]

A text like the Catechism of the Council of Trent, published with the authority of the Roman Pontiff for the universal Church, and repeatedly commended by his successors, can arguably be considered as an expression (or at least as having become an expression) of the universal and ordinary magisterium, in and of itself.[20] But whatever one thinks of this use of terms, its authority is unparalleled by other texts in the same genre.

Subscribe to stay in touch:

Comparison with John Paul II’s Catechism of the Catholic Church

Doubtless another question arises: why do we need a catechism that is several centuries old, when we have a contemporary one that has been published by John Paul II?

Is the modern catechism not a better source for us to seek the unity of faith? After all, did not John Paul II call it “a valid and legitimate instrument for ecclesial communion and a sure norm for teaching the faith”?[21]

But we may start by asking: to which version of the new catechism should we turn to seek this unity of faith and communion? The versions initially published in 1992, or those revised in 1997?[22] Or should we turn to the 2018 version, with its “minor” revision on the death penalty?

These questions may be a little facetious, but there is a serious question to be asked regarding recent changes. The pre-2018 version teaches that the death penalty is morally licit, while the 2018 version teaches that “the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”[23]

Prior to this change, the legitimacy of the death penalty appears to have been considered to be a matter of divine revelation.[24] Even the new version in the new catechism admits that the Church had “long considered” the death penalty to be “an appropriate response”.

But in fact, the 2018 version tells us, it is now “inadmissible.” It certainly appears that the two versions of this same text stands in condemnation of the other, and at least seems to entail the impossible idea that the Church was wrong about a grave matter of morality for centuries.

It will not do to claim that this matter was not definitively taught prior to 2018, nor that it is a matter which does not affect the lives of the faithful. It very much affects those found guilty of capital crimes, victims of crime, their families, judges, politicians and legislators.

In brief, it is far from clear that any of these versions of the “Catechism of the Catholic Church” can form “a sure norm for teaching the faith,” or that they have successfully brought about the unity of “ecclesial communion.”

Further, none of this even considers that John Paul II’s catechism is the catechism of Vatican II par excellence. Its opening paragraphs express its intentions:

“This catechism aims at presenting an organic synthesis of the essential and fundamental contents of Catholic doctrine, as regards both faith and morals, in the light of the Second Vatican Council and the whole of the Church’s Tradition.”[25]

The new catechism does indeed present things in the light of Vatican II, and teaches its controversial doctrines of religious liberty,[26] ecumenism[27] and other features of the ecclesiology of Lumen gentium.[28] These are the doctrines which have been so hotly disputed since the Council itself on the grounds that they contradict the prior teaching of the Church, to which all are bound.

We all know the extent of doctrinal chaos which we are facing today. For whatever reason, the modern Catechism has not held back this flood.

Here we arrive at the controverted topic the epistemology of the crisis. Once we have been “put on alert” by our inability to reconcile apparently contradictory propositions, we have a duty to leave the “passive” state of a student, and to try “actively” to work out whether there is a real contradiction, and which of the two propositions truly requires our intellectual assent.

But before we can make any sense of what’s going on, we first have to know what we must believe – what the teaching of the Church actually is. The essence of the current crisis – however it is to be explained – is that we are frequently unable to attain clarity here. In this sort of confusion, it seems legitimate to ask where else we might be able to turn – both about this matter, and about the whole of the Faith.

For example, with regards to the death penalty, the Roman Catechism teaches us with clarity. It calls the death penalty “lawful,” explains the matter in enough detail, and even states that the just use of this measure “is an act of paramount obedience to [the fifth] commandment which prohibits murder.”[29]

As I have argued elsewhere regarding theology manuals, and here with the Roman Catechism: our unprecedented crisis requires us to turn to the truly sure norms of the faith, namely the many authorised texts from before this period of confusion.

The Roman Catechism and the crisis in the Church

In the midst of confusion, the first thing that Catholics must do – before trying to construct theories to explain the situation – is to adhere firmly to the Catholic Faith.

The Church Father St Vincent of Lerins famously tells us that we believe what has been believed “everywhere, always and by all” – and then considers what we should do in cases of confusion:

“What, if some novel contagion seek[30] to infect not merely an insignificant portion of the Church, but the whole?

“Then it will be [our] care to cleave to antiquity, which at this day cannot possibly be seduced by any fraud of novelty.”[31]

In other words, we can leave those who seek to explain or nuance this matter one way or another, and turn instead to the monuments of tradition. But there is no need to conduct a detailed survey of the Fathers, the decrees of the ancient councils or even works of theology: we are able to turn to texts like the wonderful, celebrated Roman Catechism.

If we know our catechism inside-out, then we will stand firm whenever we hear anyone contradicting or obscuring its teaching.

With the Roman Catechism, we have the assurance that it teaches the faith which we are bound to believe. This importance of the Roman Catechism was a key theme in post-conciliar discourse. As an example, in famous 1976 sermon in Lille, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre reported that he had made the Roman Catechism a key part of his appeal to Paul VI:

“‘Lastly, give us back our catechism following the model of the Catechism of the Council of Trent, for without a precise catechism, what will become of our children tomorrow, what will become of future generations? They will no longer know the Catholic Faith; we are seeing that already.’

“Alas, I received no reply, except for the suspension a divinis.”[32]

In his Open Letter to Confused Catholics, answering the question of what families can do in this current crisis, he writes:

“Read and re-read as a family the Catechism of Trent, the finest, the soundest and the most complete.”[33]

Why did he place so much emphasis on this Catechism over all others? Because, as we have seen, we have the assurance that it teaches the faith which we are bound to believe. In the midst of confusion, the first thing that Catholics must do – before constructing theories to explain the situation – is to adhere firmly to the Catholic Faith. Again in his famous 1976 sermon at Lille, Archbishop Lefebvre expressed the role that catechisms generally play in this initial epistemology of the crisis:

“A child of five with his catechism can answer his bishop very well. If his bishop were to tell him, ‘Our Lord is not present in the Holy Eucharist.’ […] Well, this child, despite his five years, has his catechism. He answers, ‘Well, my catechism says the contrary.’ Who is right? The bishop or the catechism? Obviously, it is the catechism which presents the faith of all time. It is simple, childlike reasoning.”[34]

Where one goes from here, which theories one proposes, and which solutions are legitimate to explain what is happening in the Church: these are all interesting questions. But it is clear that the exchange above represents the universal starting point of the traditionalist response to Vatican II and the crisis in the Church.

In May 1976, the Archbishop summarised the issue to an association of French Catholic families:

“For this much is certain: If we remain faithful to our Creed; if we remain faithful to our catechism— to our old catechism of the past, which flowed from the Catechism of the Council of Trent, that Council which made such a magnificent catechism, the summary of the whole Catholic Faith—if we remain faithful to this catechism; if we remain faithful to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass as the Church has always celebrated it, so as to be sure that Our Lord Jesus Christ is present on our holy altars and that in the Holy Eucharist we are receiving the Body and Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ; if we remain faithful to the Sacraments and to devotion to the Most Blessed Virgin, then we are sure of being in the right. We are sure of following the true shepherd, Our Lord Jesus Christ.”[35]

Leaving aside all a priori theories about what is going on and what our proper response to the crisis should be, we know that these texts, and that of other approved sources, present the true, safe and obligatory doctrine that is imposed on our consciences. Today, the light of these texts must illuminate both the object of our faith and our assessment of the crisis itself. In this sense, the Roman Catechism is one of the most important texts available to the Catholic in this terrible Passion of the Church.

But having seen earlier the magisterial nature of this catechism, and its importance for our time, what are we to say of its actual nature? How is it structured, what is it like?

The nature and structure of the Roman Catechism

McHugh and Callan write that the catechism is a “vade mecum” for all priests and ecclesiastical students.[36]

For priests, “it is not only a review of his former studies, but an ever-present and reliable guide in his work as pastor, preacher, counsellor, and spiritual director of souls.”[37] For students, it is “a recapitulation of all the more important and necessary doctrines he has learned throughout his theological course.”[38]

They even consider it to be very appropriate for “the educated layman, whether Catholic or non-Catholic, who desires to study an authoritative statement of Catholic doctrine.” For such a person, they write:

“No better book could be recommended than this official manual; for in its pages will be found the whole substance of Catholic doctrine and practice, arranged in order, expounded with perspicuity, and sustained by argument at once convincing and persuasive.”[39]

But is it a dry book? It is true that some translations can be difficult to read – and the previous version published by Baronius was a challenge due to the translation and the headings. But McHugh and Callan’s text draws away any obscurity and allows us to see its substance clearly. They themselves defend the Roman Catechism from all charges of dryness or coldness:

“There is no single-volume work which so combines solidity of doctrine and practical usefulness with unction of treatment as does this truly marvellous Catechism. From beginning to end, it not only reflects the light of faith, but it also radiates, to an unwonted degree, the warmth of devotion and piety.”[40]

Like many catechisms since, the Roman Catechism divided its topics into four main heads: the Creed, the Commandments, the Sacraments and Prayer.

Its treatment of the Creed and the Sacraments, “while dealing with the profoundest mysteries,” is nonetheless “full of thoughts and reflections most fervent and inspiring.”[41] The section on the Commandments “teaches us in words burning with zeal,” and the final part “is doubtless the most sublime and heavenly exposition of the doctrine of prayer ever written.”[42]

Conclusion

To summarise then, the Roman Catechism is:

“A handbook of dogmatic and moral theology, a confessor’s guide, a book of exposition for the preacher, and a choice directory of the spiritual life for pastor and flock alike.”[43]

No other catechism has occupied a comparable place in the life of the Church. Every Catholic home should contain a copy of the Roman Catechism. This important text is the foundation of an educated approach to the Catholic religion. I have written elsewhere of the importance of theology manuals for our current day, and the Roman Catechism fills an important stepping-stone towards the more scientific approach to the Faith they express. It contains the most fundamental doctrines of the faith, proposed and explained with clarity: and a solid foundation like this is vital for keeping us grounded in further studies. And as the pictures make clear, the Baronius Press edition (paid link) is the one that should be on our shelves.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing our articles free for everyone. If you have benefitted from our content please do consider supporting us financially.

A small monthly donation, or a one-time donation, helps ensure we can keep writing and sharing at no cost to readers. Thank you!

Single Gifts

Monthly Gifts

Subscribe to stay in touch:

Follow on Twitter and Telegram:

[1] For the background to these headings, see The Catechism of the Council of Trent (hereafter “RC”), trans. John A. McHugh and Charles J Callan, Baronius Press, 2018. Introduction by McHugh and Callan xxxiii.

[2] Ibid xxvi

[3] RC xxvi

[4] RC xxvii

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid. xxxiv

[9] Ibid. xxxv

[10] Ibid. Depuis le jour, no. 23. Available here : https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_08091899_depuis-le-jour.html

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. Xxxvi-xxxvii

[15] Ibid. xxxvii

[16] Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton, What is Sacred Theology? (previously published as The Concept of Sacred Theology) Cluny Media, Providence RI, 2018, 118

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Chapter IV of Vacant’s The Ordinary Magisterium of the Church and its Organs, as yet unpublished in English by us. He later goes on to say: “Nevertheless, there is the affirmation of some opinions which, while being the most probable, are discussed by theologians.” As such, the various statements must be taken as they are given: those things that are affirmed absolutely as of faith are to be taken differently to things asserted as probably opinions, and so on. Cf. also Nau, Encyclicals A Doctrinal Source, also forthcoming from us.

[20] I am aware that some would object to this use of terminology on two possible grounds, neither of which are relevant for this discussion. Cf. how JMA Vacant again singles out the Roman Catechism in his discussion of the organs of the universal ordinary magisterium: “But they [‘the beliefs of the universal Church’] will be found even more surely […] in the Catechism of the Council of Trent and in the whole body of diocesan catechisms, drawn up for the guidance of the clergy of the parishes in the day-to-day instruction of the believers. These are in fact documents in which the Apostles and their successors formulated rules of faith for the faithful, and rules of teaching for pastors, by means of which the unity of doctrine is maintained.” See also his final chapter and conclusion. Chapter II available here: https://wmreview.co.uk/2021/08/27/vacant-oum-introduction-chapter-ii/

[21] John Paul II, Apostolic Constitution Fidei Depositum 1992, part IV. Available at: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_constitutions/documents/hf_jp-ii_apc_19921011_fidei-depositum.html

[22] Available here: https://web.archive.org/web/20210227184503/http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/updates.htm

[23] New version of CCC 2267: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P7Z.HTM

[24] This is proved in Chapter 3 of Feser and Besette’s By Man Shall His Blood be Shed, Ignatius Press, San Francisco CA, 2017.

[25] “Catechism of the Catholic Church” no. 11, available at https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P4.HTM

[26] 2014-2019

[27] 819

[28] Cf. 816 and surrounding paragraphs.

[29] The Catechism of the Council of Trent, Tradivox Vol. VII, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH, 2022, p 440

[30] Note that he says “seek”. It is not possible for the error to actually overcome the whole.

[31] St Vincent of Lerins, Commonitorium against Heresies, Translated by C.A. Heurtley. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 11. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1894.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. <https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3506.htm>. Chatper 3, n. 7

[32] Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, A Bishop Speaks – Writings and Addresses 1963-1976, Angelus Press, KC Missouri, 2007. Ebook version, page 457.

[33] Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, Open Letter to Confused Catholics, Angelus Press, KC Missouri, 2010, 186.

[34] Lefebvre, A Bishop Speaks 462.

[35] A Sermon delivered by His Grace, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre on Sunday, May 2, 1976 before an association of Catholic families in Southern France. Available at http://sspxasia.com/Documents/Archbishop-Lefebvre/Sermon_by_Archbishop_Lefebvre_on_May_2_1976.htm

[36] RC xxxviii

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid. xxxviii

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.