Guide to the Good Friday Liturgy

In this series, we have been considering how the Church uses her liturgy and liturgical year to show us who Christ really is, and to draw us into union with him.

During Septuagesima and Lent, the Church has us consider our fallen state and our need for a redeemer. On the Sundays of Lent, she presents Christ full of nobility and grandeur, and only after this does she present us with Christ in his sufferings.

In the previous parts, we considered Christ’s silence and composure amidst these sufferings – especially as they are commemorated liturgically on Passion Sunday and Palm Sunday. Holy Thursday shows that he suffered the passion not as a passive victim of circumstances, but specifically because he desired to do so.

This is because his passion was the offering of the perfect sacrifice to God, offered on behalf of fallen man. No man in history but Christ could have offered this sacrifice, as he was the only person who was not only true man, but also true God.

The atonement achieved by Christ is a great mystery, as well as a great confusion to some. It represents his great triumph on earth, as I have explained elsewhere.

But there is little of this sense of triumph in Good Friday’s Tenebrae service (Matins and Lauds). Consider this responsory as an example:

Resp. 1: All my friends have forsaken me, and mine enemies have prevailed against me; he whom I loved hath betrayed me. Mine enemy sharpeneth his eyes upon me; he breaketh me with breach upon breach: and in my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink.

℣. I am numbered with the transgressors; and my life is not spared.

Thus the Church certainly gives full voice to Christ’s interior sorrow on Good Friday.

But if we look closely at Good Friday’s main liturgical rite (“The Mass of the Presanctified”), we might be surprised at how full of triumph and power it is.

This Good Friday liturgy can be disorientating. In some ways, the liturgy resembles a Requiem Mass: black vestments, unbleached candles and texts sparser than those to which we are accustomed. It features four separate parts, and it might be hard to see how they fit together.

However, if we see the Passion as Christ’s triumph, the rite’s structure and meaning become much clearer.

Let’s take a look at the first part.

The First Reading and Tract

The first reading is taken from the prophet Osee, and talks of God striking us – and even hewing and slaying us, by the words of the prophets. But amidst this violent language, it already talks of the resurrection on the third day, and of God’s mercy.

The tract, taken from the prophet Habacuc, responds to the reading by continuing a sense of awe and fear in the face of God’s wrath.

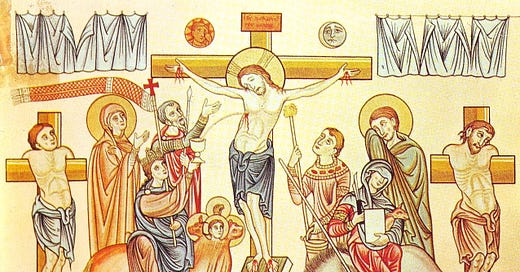

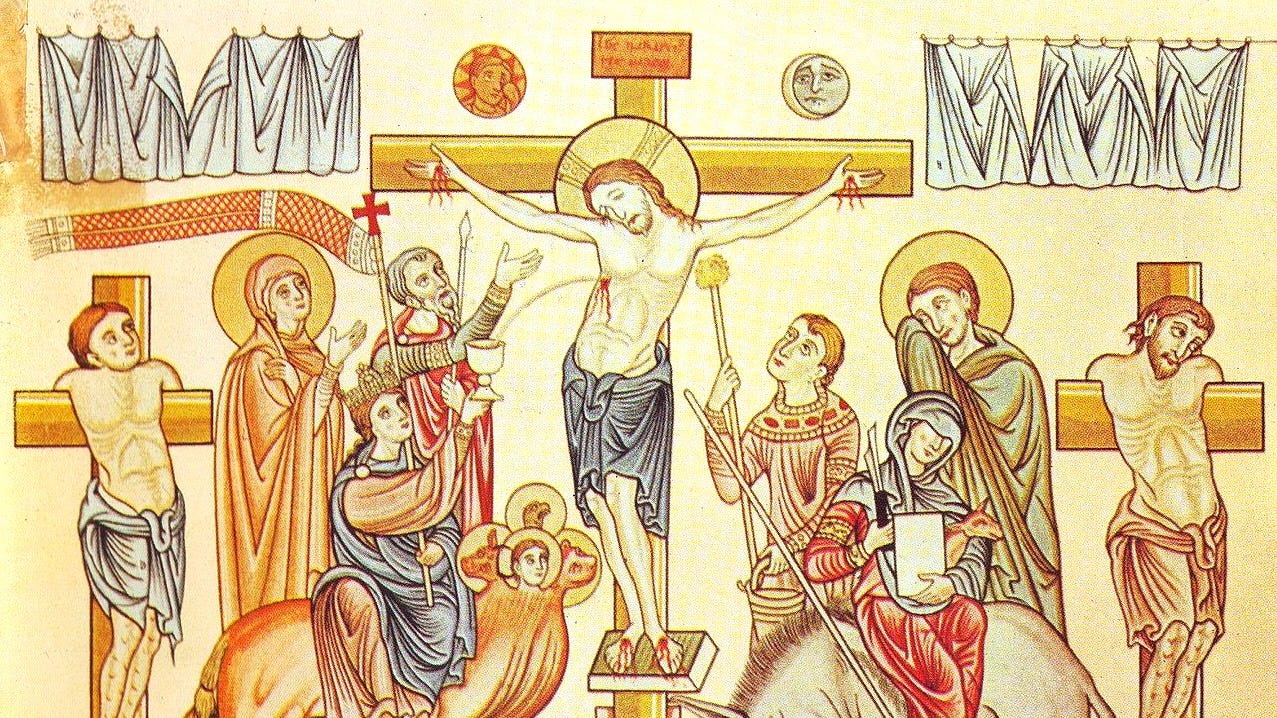

It sings of how “in the midst of two animals [God] shall be made known.” This unusual text (which does not appear in the Vulgate) is variously understood as referring to the two Cherubim of the Ark of the Covenant, the Ox and Ass of Bethlehem, and the two thieves on Golgotha.

But unlike many of the propers of Passiontide (such as Psalm 21 on Palm Sunday), it is not at all obvious that these sentiments of fear and trembling are to be put on Christ’s lips. Instead, it seems rather to be humanity that is afraid of the coming wrath of God.

It is right that we should be afraid: our race is not only guilty of an ocean of sin, but also of the unspeakable crime of deicide – “the killing of God”, in his human nature. As we shall see, the gravity of this crime figures much more in the rite than meditations on Christ’s sufferings themselves.

How are we to be delivered from the wrath which we have heard about in this reading and tract?

The Passover

The second reading is a set of Moses’ explanation of exactly how the Hebrews are to perform the annual Passover ritual.

This somewhat prosaic reading might seem bewildering, but hearing it today casts Christ’s sacrifice as the fulfilment of what was achieved and promised in the original Passover in Egypt.

It casts a light on the subsequent tract which might be different from what we would expect. The tract begins:

Tract: Deliver me, O lord, from the evil man; rescue me from the unjust man.

Who have devised wickedness in their heart; all the day long they have designed battles. […]

Keep me, O Lord, from the hand of the sinner; and from unjust men deliver me. (Ps. 139)

As with the previous tract, it is not clear that these words are to be taken as those of Christ. We know that Christ longed for this hour of suffering, and willingly offered himself to his suffering with all his heart. The passion itself would not have occurred if Christ had been “kept from the hand of the sinner” or had been “delivered from unjust men”.

On the contrary, this tract is sung as a response to the reading from Exodus, which recounts the deliverance of the Hebrews from Pharoah and from slavery in Egypt.

In this light, it seems to be our cry, calling for Christ to fulfil what was foreshadowed in the Exodus, and so deliver us from the unjust servitude to Satan in which sin has placed us. The psalm fits more naturally into this paradigm than as a naturalistic view of Christ’s sentiments during the Passion.

The Passion according to St John

Immediately following this tract, we are presented with the sung Passion of St John. This position casts the passion as the fulfilment of the original Passover in Exodus, and of the prayer for deliverance in the tract.

All the accounts of the passion present Christ as serene, composed, and silent, and this is most clear in the account of St John. This has already been the subject of previous parts in this series, so there is no need to repeat it here.

At the end of the Passion, we genuflect at the moment at which Christ dies, and are silent. Following this, the narrative continues in the same simple and distinctive tone – until we reach the prophecies that Christ’s bones will not be broken, and that “they shall look on him whom they pierced.”

At this moment – whether as a Gospel reading in the traditional form, or continuing directly as in that of Pius XII – the tone changes dramatically. This tone, when sung well, has the capacity to convey both the power of the earthquake following Christ’s death, and the gravity of our race’s crime.

As this last section continues, we are told that Jesus is laid in the sepulchre – at which point the reading ends.

And there we have it. The question of how our race is to appease the wrath of God is answered: by the sacrifice of Christ, our great High Priest.

As we hear this tone, singing of the burial of the Son of God, we might as ourselves: “What have we done?”

The Solemn Prayers

At that, the Church’s ministers begin “the solemn prayers.” In brief, these prayers might manifest the prayer offered by our High Priest both on the Cross, and even now in Heaven. After all, in the letter to the Hebrews, we are told:

“[Christ] hath an everlasting priesthood: Whereby he is able also to save for ever them that come to God by him; always living to make intercession for us.” (Heb. 7.24-5)

These are not “Bidding Prayers” themed around current affairs, as we see elsewhere. They are the timeless prayers of a High Priest who is now a King, reigning over the earth. Rather than being bewildered by this long series intercessions, we can use this opportunity to enter into Christ our High Priest, and join our Head in prayer as members of his mystical body.

But following these prayers comes a striking rite, which is unlike anything else in the Church’s liturgy.

The Adoration of the Cross

The twentieth century liturgical writer Fr Johannes Pinsk writes:

“It is the unveiling and veneration of the cross which reveals to us the innermost meaning of the entire Good Friday liturgy.”1

Very little about this ceremony of adoration is tender or mournful. As the cross is gradually unveiled, the thrice-rising chant tone is powerful and impressive – quite unlike the meditative tone used in the tracts.

Pinsk points out that “the cross is a royal throne and judgment seat, albeit the judgment is a judgment of mercy and grace.”2 As the hymn Vexilla Regis sings, God “hath reigned and triumphed from the Tree.” This is crucial for understanding this part of the rite.

We abase ourselves before the cross, and process forward to venerate it. As this veneration is taking place, the choir sings “The Reproaches.” These are some of the most celebrated parts of the rite, and of the Church’s liturgy as a whole. They are sung as the words of Christ to his people. Although “his people” in this context primarily and literally applies to the Jews and all that God did for them, these words have a metaphorical application to us:

O my people, what have I done to thee? or wherein have I afflicted thee? Answer me!

Because I led thee out of the land of Egypt, thou hast prepared a cross for thy Saviour.

Because I led thee out through the desert forty years: and fed thee with manna, and brought thee into a land exceeding good, thou hast prepared a Cross for thy Saviour.

What more ought I have done for thee, that I have not done? I planted thee, indeed, My most beautiful vineyard: and thou hast become exceeding bitter to Me: for in My thirst thou gavest Me vinegar to drink: and with a lance thou hast pierced the side of thy Saviour.

These texts are often treated as if they are a mournful lamentation of a sorrowing Christ, but this is hard to justify when we examine the text more closely.

First, as Pinsk points out:

“The oft-repeated antiphonal cry, ‘O my people, what have I done to you; wherein have I afflicted you? Answer me!’ is not a lamentation but an accusation leveled by the Lord exalted upon the cross against his faithless people.

“And the congregation answers them not with expressions of sympathy but rather with the repeated cry: ‘O holy God! O holy strong One, O holy immortal One, have mercy upon us.”3

This part of the rite – the centre of Good Friday liturgy itself – is full of power and authority. Sinful humanity is called to account in a sort of preparation for the Final Judgment, and given an opportunity to seek reconciliation with he who was “bruised for our sins” (Is. 53.5). In our individual veneration of the Cross, we accept the justice of these accusations, just we accepted the death sentence imposed on each of us in Adam on Ash Wednesday.

But this is not all. Pinsk continues:

“This ceremony represents a public homage, celebrating the triumph of the Cross […]

“Each individual member of the people of Christ performs the act of homage to his Lord exalted upon the cross by kissing that cross. This kiss is at once a sign of joyous union with the Lord triumphant in his Passion and a token of thankful homage for the sovereign love he has shown for us in that Passion.

“The essential fruit of the Good Friday rites for every congregation is that each member shall learn to affirm faith in the triumph of the cross in the liturgical rite and then be able to celebrate that triumph personally by his conduct and posture in public as well as private life.”4

In other words, this rite is our opportunity to recognise the social kingship of Jesus Christ, and to pay our solemn homage to him.

As the Reproaches continue, humanity’s cry (“O holy God! Etc.) ceases, and we listen in silence to the remaining accusations of our King. But as soon as the Reproaches finish, we find our voice again, and the Church sings the following antiphon linking Christ’s cross and resurrection:

Ant.: We adore Thy Cross, O Lord: and we praise and glorify Thy holy Resurrection: for behold by the wood of the Cross joy has come into the whole world.

Is it not striking that on Good Friday, we sing such a text recalling the resurrection – and that we sing it to the same melody as the great hymn of praise, Te Deum laudamus?

Immediately after this, the choir sings out the antiphonal hymn Crux Fidelis. The following phrases show that it is very far from being a mournful meditation on passive suffering:

Sing, my tongue, the glorious battle

With completed victory rife!

And above the Cross’s trophy

Tell the triumph of the strife:

How the world’s Redeemer conquer’d

By the offering of His life.Bend thy boughs, O Tree of glory!

Thy relaxing sinews bend;

For awhile the ancient rigor,

That thy birth bestowed, suspend:

And the King of heavenly beauty

On thy bosom gently tend!Thou alone wast counted worthy

This world’s ransom to uphold;

For a shipwrecked race preparing

Harbor, like the Ark of old;

With the sacred Blood anointed

From the smitten Lamb that rolled.

At this, the liturgy is practically finished. All that remains is for the Blessed Sacrament to be consumed, and for us to be left with an empty tabernacle – just as Our Lady and the others were left with an occupied tomb.

The Holy Communion

In the traditional rite, the sentiment of the Crux Fidelis continues even now. As the ministers bring the Blessed Sacrament from the Altar of Repose, the choir sings the Vexilla Regis:

The royal banners forward go

The Cross shines forth in mystic glow,

Where life Himself our death endured,

And by His death our life procured.Fulfill’d is all that David told

In true prophetic song of old

To all the nations: “God,” saith he,

“Hath reigned and triumphed from the Tree.”

The following rite is very short. Traditionally, Holy Communion was limited to the priest alone – which may also have made the congregation reflect more on the gravity of the crimes committed in the passion, and recalled the loss experienced while Christ lay dead in his human nature.

With this part of the rite complete, the liturgy is over, and a mournful Vespers is often sung.

Conclusion

Good Friday’s Mass of the Presanctified has a very different emphasis to that of Tenebrae, as well as the Stations of the Cross and the Seven Last Words. These popular devotions commemorate the bitterness of Christ’s passion, and place themselves alongside the sentiments we discussed in relation to the Mass of Palm Sunday.

But in this main liturgical rite of Good Friday, we see that we really caused these sufferings to Christ, and that we must repent and submit to him as the head of the Church, outside of which there is no salvation.

In this, the Good Friday rite has more in common with Passion Sunday, which is full of dignity, power and authority. It shows that Christ’s sufferings are ordered towards our redemption, and establish him as the triumphant High Priest and King.

“And all of this” says Pinsk: “[W]e must emphasize the point again and again – in the somber darkness and sorrow of Good Friday!”5

This may seem strange, but it shows that Good Friday admits a wider and richer range of truths than we might expect. Pinsk continues:

“The Church is evidently celebrating this day from an entirely different point of view than the one we usually ascribe to her.

“Who must be re-educated, the Church or we ourselves?”6

Who indeed? If we approach the Church’s liturgy limited by our preconceived notions, we miss the opportunity to be formed by her and drawn into life with Christ.

I hope that some of these considerations are helpful to readers as we approach the holy rites of the Triduum. We should study and appreciate these rites, not just for their aesthetic value – or even just for their doctrinal interest. As Pius XII taught in Mediator Dei:

“[The liturgical year] requires a diligent and well ordered study on our part to be able to know and praise our Redeemer ever more and more.

“It requires a serious effort and constant practice to imitate His mysteries, to enter willingly upon His path of sorrow and thus finally share His glory and eternal happiness.”7

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Read Next:

Further Reading:

Dom Prosper Guéranger – The Liturgical Year

Fr Johannes Pinsk – The Cycle of Christ

Dom Columba Marmion – Christ in his Mysteries

Mgr Robert Hugh Benson – Christ in the Church

Fr Frederick Faber – The Precious Blood

Fr Leonard Goffine – The Church’s Year

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Johannes Pinsk, The Cycle of Christ, p 44. Trans. Arthur Gibson, Desclee Company, New York, 1966.

Fr Johannes Pinsk (1891-1957) was involved with the twentieth century liturgical movement in ways that many readers would consider regrettable. However, his works have a wealth of interesting information about the liturgical year, which I would like to share. They also contains some things which traditional Catholics might not appreciate. My purpose here is to present what is good, along with some comments, to help us appreciate the holy Roman Liturgy.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. 55-6.

Ibid.

Ibid. 56

Pius XII, Encyclical Mediator Dei, 1947, n. 161. https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_20111947_mediator-dei.html