Is the Church infallible in her discipline and rites? Abbé Hervé Belmont

It's often assumed that the Church's discipline is fallible. Abbé Hervé Belmont demonstrates, with a host of authorities, that the Church cannot give us harmful, dangerous or evil laws or rites.

The following text is by l’Abbé Hervé Belmont, translated by The WM Review and published with his permission.

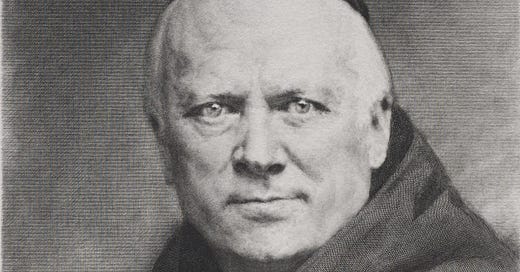

Fr Belmont is a priest located in Saint-Maixant, France. He was ordained by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, and he adheres to what is known as “The Thesis of Cassiciacum”, developed by the late Bishop Guérard des Lauriers. His articles and essays are available in French at Quicumque.com, and we are very happy to be publishing some of them in translation here.

The latter part of this piece features a number of texts from theologians supporting Fr Belmont’s thesis. We have supplemented this selection with some extra texts, as well as supplying parts of the texts missing in the original French.

The Infallibility of General Disciplinary Laws

By Abbé Hervé Belmont

The Holy Catholic Church is undergoing a kind of disgrace, in that her members – the faithful of Jesus Christ – are all too often unclear about several very important things:

Her exact nature – of being the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ

Her threefold mission – viz. her power to teach, sanctify and govern

Her attributes – indefectibility, infallibility, visibility.

Therefore, in the difficulties that accompany the life of the Church here on earth, it happens that her members sometimes (or often) react to things in a confused or even heterodox way.

Here, then, are some points which establish one of her qualities – one which is often ignored and yet is theologically certain. The Church possesses this quality by virtue of her divine origin and the permanent assistance granted to her by the Holy Ghost.

Practical Infallibility

In the establishment of general disciplinary laws, the Catholic Church cannot err. Of course, this is a practical infallibility, which guarantees that a given law is neither bad, nor harmful, nor burdensome. In other words, it guarantees that the one who abides by a given law is in the way of eternal salvation – at least in the matter of the given law itself.

It is not directly a question of doctrinal infallibility, although the doctrinal presuppositions or consequences of the said laws are also thus guaranteed.

This infallibility also does not guarantee that the law is the best that it could be, but it does guarantee that the law is good in itself.

This infallibility does not, therefore, prevent the legitimate and competent authority of the Church from changing her laws; and in such a case, we will be assured that the new law will still be good – even if the former was better.

Magisterial Authorities

Since this truth is often very much misunderstood, we present some texts of the Magisterium which teach it unequivocally. These documents are echoed in all the classical theological textbooks.

Condemned Proposition n. 78: “… the Church, which is ruled by the Spirit of God, could establish a discipline not merely useless and insupportable for the Christian spirit, but even dangerous, harmful, and conducive to superstition and to materialism. [Condemned as:] false, temerarious, scandalous, pernicious, offensive to pious ears, injurious to the Church and to the Spirit of God who guides her, at the least erroneous.

Pius VI, Auctorem fidei (condemnation of the Council of Pistoia).

Denzinger 1578; Pontifical Teachings, the Church (Solesmes) n. 122.

“Is it possible that the Church, which is the pillar and ground of truth and which is continually receiving from the Holy Spirit the teaching of all truth, could this Church ordain, grant, permit what would turn to the detriment of the soul’s salvation, to the contempt and harm of a sacrament instituted by Christ?”

Gregory XVI, Quo graviora, in Pontifical Teachings, The Church (Solesmes) n. 173

Naturally, the above question from Pope Gregory XVI is rhetorical. His answer is an emphatic “no”.

“But this [a matter of the Church’s government] is not to be determined by the will of private individuals, who are mostly deceived by the appearance of right, but ought to be left to the judgment of the Church.

“In this all must acquiesce who wish to avoid the censure of Our predecessor Pius VI, who proclaimed the 78th proposition of the Synod of Pistoia [given above] ‘to be injurious to the Church and to the Spirit of God which governs her, inasmuch as it subjects to scrutiny the discipline established and approved by the Church, almost as though the Church could establish a useless discipline or one which would be to onerous for Christian liberty to bear.’”

Leo XIII, Testem benevolentiæ, in Pontifical Teachings, The Church (Solesmes) n. 631

This infallibility is especially guaranteed when it comes to the liturgy (viz. the sacramental rites).

“Can. 13. If anyone shall say that the received and approved rites of the Catholic Church accustomed to be used in the solemn administration of the sacraments may be disdained or omitted by the minister without sin and at pleasure, or may be changed by any pastor of the churches to other new ones: let him be anathema.”

[“Can. 7. If anyone says that the ceremonies, vestments, and outward signs, which the Catholic Church uses in the celebration of Masses, are incentives to impiety rather than the services of piety: let him be anathema.”]

Council of Trent, Denzinger 856, 945. The second canon added by The WM Review

Permissions

One more little clarification. In her general disciplinary laws, the Church is infallible not only in what she commands, but also in what she allows. This is what Pope Gregory XVI teaches in passing, in the text quoted above.

This infallibility of the Church’s laws cannot therefore be denied or rejected under this vain pretext: “This practice (or this rite) is not obligatory, it is only permitted. There are no guarantees.”

In this case, one would have to admit that one could say, for example: “It is not impossible that the Church might authorise polygamy; practical infallibility only guarantees that it will not impose it…”

We can see the aberrations to which this argument could lead.

Theological Authorities

Here, in confirmation of this certain truth, are two texts by Dom Guéranger and some extracts from classical theologians.

Dom Prosper Guéranger

Institutions Liturgiques

In relation to the criticism of liturgical laws, Dom Guéranger writes:

Otherwise, it would have to be said that the Church would have erred in her general discipline, which is heretical.

Institutions Liturgiques, Tome II page 10 (ed. 1878)

In the same work, he writes:

Ecclesiastical discipline is the set of external regulations established by the Church.

This discipline may be general, when its regulations emanate from the sovereign power in the Church, with the intention of obliging all the faithful, or at least a class of the faithful, except for the exceptions granted or consented to by the power which proclaims the given discipline.

It is particular, when the regulations emanate from a local authority which proclaims it within its jurisdiction.

It is an article of Catholic doctrine that the Church is infallible in the laws in which her general discipline consists – so that it is not permissible to maintain, without breaking with orthodoxy, that a regulation emanating from the sovereign power in the Church with the intention of obliging all the faithful, or at least a whole class of the faithful, could contain or favour error in faith or in morals.

It follows from this that, apart from the duty of submission in conduct, imposed by general discipline on all those whom it governs, we must recognise a ‘doctrinal value’ in ecclesiastical regulations like this.

The practice of the Church confirms this conclusion. Indeed, when it comes to making decisions about matters of faith, whether at general councils or in apostolic judgments, we often see the Church basing herself on the laws which she has established for the government of Christian society.

Any practice which represents a point of belief is universally protected from error in the Church: therefore, the belief represented by the practice is orthodox, since the Church cannot profess error, even indirectly, without losing the note of holiness in doctrine – a note which is essential to her until the final consummation. […]

Discipline is therefore directly related to the infallibility of the Church, and this is already an explanation of its high importance in the general economy of Catholicism.

Dom Prosper Guéranger, “Troisième lettre à Mgr l’évêque d’Orléans”,

in Institutions liturgiques, second edition, Palmé, 1885, vol. 4, pp. 458-459.

Louis Cardinal Billot

Treatise on The Church of Christ

Thesis XXII: The legislative power of the Church has as its subject matter both that which concerns faith and morals, and that which concerns discipline.

In matters of faith and morals, the obligation of ecclesiastical law is added to the obligation of divine law; in matters of discipline, all obligations are of ecclesiastical law.

However, infallibility is always attached to the exercise of supreme legislative power, insofar as the Church is assisted by God so that she can never institute a discipline which would be in any way opposed to the rule of faith or to evangelical holiness.

Card. Billot, De Ecclesia Christi, Rome, 1927, volume I, p. 477

Fr Herrmann CSSR

Institutiones Theologicæ Dogmaticæ:

The Church is infallible in her general discipline.

By ‘her general discipline’ is meant her laws and institutions which concern the external government of the whole Church – for example, that which concerns external worship, such as the liturgy and rubrics, or the administration of the sacraments […]

The Church is said to be infallible in her discipline, not as if her laws were immutable, for changing circumstances often make it expedient to abrogate or change laws; nor as if her disciplinary laws were always the best and most useful… Rather, she is said to be infallible in her discipline in this sense: nothing which is opposed to the faith, or to good morals, or which may act to the detriment of the Church or to the prejudice [‘damnum’] of the faithful – nothing of this sort can be found in her disciplinary laws.

That the Church is infallible in her discipline follows from her very mission. The mission of the Church is to keep the faith intact, and to lead the people to salvation by teaching them to observe all that Christ has commanded. But if in disciplinary matters she could stipulate, impose or tolerate what is contrary to faith or morals, or what would be to the detriment of the Church or to the prejudice of the people, then the Church could deviate from her divine mission – which is impossible.

This is implied by the Council of Trent, Sess. xxii, can. 7:

“If anyone says that the ceremonies, ornaments, and external signs which the Catholic Church employs in the celebration of Masses are incentives to impiety rather than helps to piety, let him be anathema.”

And by Pius VI in the constitution Auctorem Fidei, concerning the 78th proposition of Pistoia:

“‘As if the Church, which is governed by the Spirit of God, could establish a discipline which is not only useless and more burdensome than Christian liberty can tolerate, but which would be, moreover, dangerous, harmful, and apt to induce into superstition or materialism.’ – A proposal which he condemned as ‘false, reckless, scandalous, pernicious, offensive to pious ears, etc.'”

R. Fr. Herrmann CSSR, Institutiones Theologicæ Dogmaticæ

with the personal approval of St. Pius X, Vol. i, no. 258.

Fr J.-M.-A. Vacant

The Ordinary Magisterium of the Church and its Organs

The implicit and infallible teachings of the ordinary magisterium are supplied to us by the universal practices of the Church; by the liturgies, in what they have in common; and by the general laws of the Church. All of the acts in conformity with these practices, liturgies, or laws are sanctioned by the depositaries of infallibility; they cannot, therefore, be evil, nor can they divert us from salvation. Whenever, therefore, these acts manifestly imply the truth of a doctrine, there is an implicit proposition of that doctrine by the Church. […]

The universal usages of the Church which have a definite purpose (such as the rites of the sacraments and of the Holy Sacrifice) manifest in another way the infallible faith of the Church. The Church uses them only because she believes in their efficacy. It must be admitted, for example, that the Church regards the matter and form used in the administration of the various sacraments as capable of producing their effects, and that she is not mistaken on this point.

Le magisterium ordinaire de l’Église et ses organes, by J.-M.-A. Vacant, 1887.

Rev. E. Dublanchy

‘Church’

Dictionnaire Théologie Catholique

I have taken the liberty of filling in the ellipses in Fr Belmont’s original piece – this is indicated by square brackets.

The infallibility of the Church must also extend to every dogmatic or moral teaching practically included in what is condemned, approved or authorized by the general discipline of the Church, [whether this discipline comes from a positive law of the whole Church or from a custom adopted or approved by the universal Church.

For example:

The liceity of the worship of the saints in so far as it is commanded or permitted

The legitimacy and excellence of religious orders approved by the Church,

The divine institution and supernatural efficacy of the sacraments

The administration of which is regulated by the ecclesiastical liturgy

The divine efficacy of the sacrifice of the Mass, as it results from the approved liturgy and the laws or customs sanctioned by the Church

Many other teachings resulting from the liturgical practices of the universal Church.]

a) This is a rigorous consequence of New Testament teaching. For the infallibility guaranteed by Jesus to his Church, according to the text of Matthew 28.20, applying to every teaching really and effectually given by the ecclesiastical magisterium, must equally apply to every teaching necessarily included in the laws, practices, or customs established, approved, or authorized by the universal Church – this practical or indirect teaching being, especially for an authority in itself infallible, quite as real and effectual as the direct doctrinal teaching.

[b) This is also indicated by the constant testimony of Christian tradition. For in all periods of the Church’s history, the Fathers, ecclesiastical writers and theologians, and even popes and councils, have often deduced proofs from universal practice, which have always been considered as demonstrations in favour of a contested doctrine.

It will suffice for us to recall briefly some of the principal facts or documents already mentioned:

Pope St. Stephen, in the middle of the third century, relying on the general practice of the Church, not to renew the baptism given by heretics, which was at least an implicit affirmation of the validity of the baptism conferred by them

St. Augustine likewise proving the value of the baptism of heretics by the ancient custom of the Church not to rebaptize those who, from heresy, return to the Catholic Church, […] or proving, by the universal fact of the administration of baptism even to infants, the dogma of original sin which defiles the souls of all the children of Adam, at the same time as the utility of baptism which is conferred before the age of reason, […];

St. John Damascene relying at least partially on the constant usage of the church to legitimise the cult of the saints and their images, […]; which was an argument also employed by the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 787,

St. Thomas, in the thirteenth century, demonstrating the efficacy of suffrages for the faithful departed by the constant custom of the Church praying for them, […] and the legitimacy of invoking the saints by the constant custom of the Church to have recourse to their prayers […]

The Council of Constance and Martin V in 1515, relying on the Church’s custom of the laity receiving Holy Communion under the species of bread alone, reproved those who condemned this custom, and to ordered that those who obstinately affirm the contrary be punished as heretics […]

The Council of Trent proving, by the long usage of the Church, the authenticity of the Vulgate […]; and the same council showing, through the constant practice of the Church, the legitimacy of the cult of adoration or latria rendered to the Holy Eucharist by the constant practice of the Church; and the worship of the saints and their images by the universal practice from the earliest times of Christianity […],

And, since the sixteenth century, the very numerous and explicit statements of theologians claiming doctrinal infallibility for the Church in these matters, as we have already indicated.]

Dublanchy, “Church”, Dictionary of Catholic Theology, cols. 2197-8.

Extra passages in square brackets supplied from the source and translated by The WM Review.

Serapio de Iragui OFM Capand Francisco Xaverio Abarzuza OFM Cap

Manuale theologiæ dogmaticæ

Included from elsewhere in Fr Belmont’s work:

Decrees of this kind are the universal laws by which man’s Christian life and worship are ordered. Although the faculty of making laws belongs to the power of jurisdiction, the power of the magisterium is involved in a special way insofar as in these laws there can be nothing that opposes the natural or positive [divine] law. In this respect we affirm that the Church’s judgment is infallible.

We do not affirm, however, that ecclesiastical laws are always necessarily the most prudent of all possible laws, nor that they are immutable and intangible; indeed, according to circumstances, different laws may exist – we can consider the various variations in canon and liturgical law, especially under Pius XII.”

Iragui-Abarzuza, Manuale theologiæ dogmaticæ, vol. i, Madrid, 1959, p. 453

Fr Sixto Cartechini SJ

De Valore Notarum Theologicarum

On the Ordinary Magisterium and implicit doctrine.

This text has been added by The WM Review, and is not present in Fr Belmont’s original piece. This text shows both that the liturgy itself cannot be harmful or contrary to the Church’s faith; and also how it can be used to prove Catholic doctrine.

1. The Church exercises her ordinary magisterium not only by expressly declaring the doctrine to be held with faith, but also through doctrine implicitly contained in her praxis – that is, in the very life of the Church.

In fact, the divine doctrine, communicated to the Church by the Word of God, or the deposit of faith, can be transmitted by written tradition, by oral tradition, and also by practical tradition.

The transmission that takes place by means of practice always presupposes some other explicit doctrine, transmitted in writing or through preaching, after which the practice was formed. For the moral, ascetic, and liturgical life of the faithful has the value of tradition insofar as it is founded on some doctrine. Therefore, any Christian practice that belongs to tradition is attached to some doctrine, which, if nothing else, consists in this: that this practice is necessary for eternal salvation, or is indicated in revelation. Our Lord, too, taught by example without the need for explicit words: for example, his attitude toward his mother is itself eloquent and demonstrates Our Lady’s holiness.

We must then note, that when we speak of the practice of the Church, that we are primarily referring to the action of the hierarchy of the Church, which directs the practice of the faithful.

2. So with regard to the liturgy, although one cannot say, as the modernists think, that it creates dogmas, nevertheless – precisely because the liturgy reflects the faith of the Church – it is proof of many dogmas, and therefore of many truths which are theologically certain.

There is no doubt that, in the way in which the Church prays and praises the Lord, she expresses what she believes, how she believes it and on the basis of which concepts she publicly honours God. And although it is not repugnant that sometimes the Church, in things of little importance, tolerates in ancient prayers some expressions which are not entirely exact, she cannot, however, permit that forms of expression be used in the liturgy, in her name, which are contrary to her beliefs and convictions.

The following themes and their consequences can be proven from the liturgy:

The dogma of the Trinity: the preface of the Mass on the feast of the Holy Trinity and the whole office can be considered a small theological treatise

The divinity of the Incarnate Word, against the Arians and Socinians, seen in numerous feasts and offices

The divinity of the Holy Spirit, against the Macedonians

The humanity of Christ: in all feasts, beginning with Christmas and ending with the Ascension

The virginity of Our Lady before the birth, during and after the birth can be proved by the same office of the Nativity of Our Lord

The primacy of St. Peter, including even that of jurisdiction, and the primacy of the Roman pontiff

That simple priests are inferior to bishops, as is clear from the text of the Roman Pontifical

With the liturgy one can refute the Pelagian and semi-Pelagian heresy. The Pelagians say that grace is not necessary or that it is required only so that acting rightly may be easier; the semi-Pelagians, on the other hand, say that grace is not necessary for the beginning of faith and for perseverance; whereas the Collects, which the Church uses in the liturgy, prove the contrary

The dogma of original sin

The dogma of the Eucharist: the office of the feast of Corpus Christi composed by Saint Thomas would suffice to prove this; the adoration of the Host presents the dogma of the real presence

The dogma of Purgatory

The dogma of the cult and invocation of the saints

The dogma of the necessity and integrity of sacramental confession is implicitly contained in the practice of the early Church

The dogma of the Assumption in the feast of that name, which is now a defined dogma.

3. As to the juridical life of the Church, it must be said that general councils and the pope cannot establish laws whose observance is sin.

For Christ gave the Church the power of jurisdiction to lead men to eternal life; but if the Church commanded OR directed men towards mortal sin in her laws, she would oblige men to lose eternal life. Nor, on the other hand, can even God dispense from the natural law. Therefore, the Church cannot define what is upright to be wicked; nor can she define what is wicked to be upright; and she cannot approve what is contrary to the Gospel or to reason.

4. Hence there can be nothing in the Code of Canon Law that in any way opposes the rules of faith or the holiness of the Gospel, since ecclesiastical legislation must necessarily be dependent on revealed moral principles, which the Church has the task of interpreting and applying for all the faithful.

Indeed, inasmuch as the Church teaches, through the Code, certain practical and speculative truths as contained in the deposit of revelation and explains and proposes them in an obligatory way, it cannot be denied that certain questions are clearly expressed.

Moreover, there are some things in the Code which we can call dogmatic facts, inasmuch as the Church determines in particular circumstances certain observances, which in divine or natural law are promulgated only in general – for example, the precept of approaching Holy Communion.

Finally, in the Code the Church also deduces more or less necessary conclusions from revealed truths, and imposes them. Therefore, whenever the Code proposes some doctrine concerning faith and morals as the basis of its prescriptions, this doctrine is to be considered as taught infallibly by the ordinary Magisterium.

Base text translated from the Italian version, compared with and adjusted in light of the Latin version published by Tradibooks.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone. If you have benefitted from our content please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material!

Thank you!

Valid Sacraments

Doubtful Baptisms – reflections on the necessity for widespread access to conditional sacraments

Is it Valid? The Proximate Matter of Baptism – a comprehensive guide to possible defects

Is the Church Infallible in her Discipline? by l’Abbé Hervé Belmont

What are the implications of conditionally repeated sacraments? – Text by Mgr Robert Hugh Benson, with commentary