Learning Sacred Theology: Fundamental and dogmatic theology

It is essential that lay Catholics have a secure grasp of fundamental theology. We must understand and be able give credible explanations about God's existence, Jesus Christ and the Catholic Church.

Theology is a science, with its own proper end and methodology. This three-part series is about how laymen can go about learning this science. I have freely gathered together notes, ideas and reading lists from various sources, particularly the Bellarmine Forums. I hope that this part will be especially helpful to those confused by the current crisis and the competing media voices.

In the first part of this trilogy, we discussed the preliminaries of learning sacred theology. These included a basic involvement in Catholic intellectual life through the following means:

Being “soaked” in the Gospels, as well as the Psalms and the New Testament (see our Old and New Testament Scriptural Rosary system).

Familiarity with the traditional liturgy

Some appreciation of St Thomas Aquinas

We then considered the foundations for adult laymen learning theology, namely the Catechism, Latin, philosophy and the acts of the magisterium. Now we are entering the realms of theology, properly speaking.

Each part of this series includes a reading list. These lists are suggestions, and one may obviously read more or less than suggested. I have put one or two texts in bold in each section, to indicate personal preferences.

1. Dogmatic Theology

Rather than turning to the texts of Fathers, Doctors or other writers, the true initiation for beginners into the science of theology is found with the genre of books known as the manuals. Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton, in The Concept of Sacred Theology, describes their role:

“Those which are adopted and utilized officially in the training of candidates for the priesthood within the Catholic Church have naturally more authority along this line than others. In so far as they are adopted and utilized by the episcopate, they may be said to express the teaching of the bishops about the matters they treat.

“To this extent, the manuals and the monographs of sacred theology may be said to express in some way the ordinary magisterium of the Church. The authority of the Scholastic theologians actually constitutes a separate and distinct theological place. However, the theological works to which we made allusion must also be considered in their place as manifestations of the teaching of the bishops throughout the world.

“In this light they appear as manifesting in some way the ordinary magisterium of the Catholic Church.”[2] [Our emphasis] (Fenton, The Concept of Sacred Theology)

These works of theology approved by the Church are safe sources of sacred doctrine. The Church takes the greatest pains to ensure that the clergy – who in turn teach the laity – are properly formed in sacred doctrine. They were written by seminary professors and other experts for the education of the clergy. As Fenton said, they can even be said to be expressions of the magisterium of those bishops who adopt them.

So how should we go about approaching this body of literature?

We could start by obtaining a two- or three-volume manual giving a complete overview of dogmatic theology. There are many which are arranged specifically for laymen, as we can tell by the fact that they were translated in the first place.

We could read a work like this all the way through, and ensure that we understand it. If we do not understand something, we should frequently call it to mind. If we never understand it, that is fine: if we recall it regularly, it will at least remind us of our own limitations.

Here is a list of appropriate texts:

Wilhelm & Scannell – Manual of Catholic Theology (2 vols.) Vol. I (and for UK readers) and Vol. II (and for UK readers). This is a nineteenth century Englishing of Matthias Scheeben’s Dogmatik, with a foreword from Cardinal Manning. Also online at the Bellarmine Forums.

Hunter, S.J – Outlines of Dogmatic Theology (3 vols.) Vol. I (UK readers), Vol. II (UK readers) and Vol. III (UK readers) Vol. I deals with the Church and fundamental theology. Please note that some versions are missing about twenty pages, which deal with membership. These pages are available here. There is a cheaper one-volume compendium, without footnotes (and for UK readers), and the three volumes are online here: Vol. I, Vol. II and Vol. III

Murphy, Donlan, Cunningham, et al. – College Texts in Theology (3 or 4 vols.) This is an excellent and very clear “trilogy of four” (in that it has an extra fourth volume on Christian marriage). Volumes I and III are available as second-hand books. Volume II and IV are extremely rare second hand. Vol. II is available as a new paperback from Wipf and Stock, and Vol. IV recently came back into print through Hassell Street Press

Vol I, God and his Creation (online at Internet Archive)

Vol. II, The Christian Life (and for UK readers and online at Internet Archive)

Vol. III, Christ and his Sacraments (and for UK readers online at Internet Archive)

Vol IV, Toward Marriage in Christ (and for UK readers and online at Internet Archive)

Wilmers – Handbook of the Christian Religion (1 vol.) (and for UK readers). More aimed at college students. Available at Internet Archive.

Parente – Dictionary of Dogmatic Theology (and for UK readers). Brief and brilliant. This is not an overview of dogmatic theology, but is a useful resource at this stage. Available from the Internet Archive.

Some other complete overviews:

Garrigou-Lagrange – Reality. An excellent work for understanding how the Thomistic synthesis interacts with the whole of revealed doctrine – but while it is certainly very worth having and reading, at least one text from the above list should be mastered too. This book is soon to be republished by Baronius Press

Sacrae Theologia Summa (Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos Series – 8 vols.) Keep the Faith Publications. This series has much to commend it, and various volumes are mentioned below. However, while it may suit certain readers, it is more advanced than an accessible 2- or 3-volume overview necessary for this stage. For the sake of completeness, however, are the texts:

Vol. IA: Introduction to Theology, and On Christian Revelation

Vol. IB: On the Church of Christ, and On Holy Scripture

Vol. IIA: On the One and Triune God

Vol. IIB: On God, the Creator and Sanctifier, and On Sins

Vol. IIIA: On the Incarnate Word, and On the Blessed Virgin Mary

Vol. IIIB: On Grace, and On the Infused Virtues

Vol. IVA: On the Sacraments in General and On Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance and Anointing

Vol. IVB: On Holy Orders and Matrimony, and On the Last Things

2. Fundamental Theology

Fundamental theology is concerned with what Fenton calls “the body of divine revelation as a whole,” as opposed to “special theology,” which “considers the individual doctrines which go to compose the message which God has given to the world through Jesus Christ our Lord.”[3]

Reading the texts listed above will give us an overview of both fundamental and special theology – but now it is time to delve, in a deeper way, into this specific branch.

Fundamental theology is sometimes divided as follows:

Methodology of Sacred Theology

Apologetics

Ecclesiology (treatise on the Catholic Church)

Holy Scripture

The fourth section is sometimes treated as a separate head, and/or treated with the “sources of revelation.” We will address the sources of revelation with ecclesiology, and leave Holy Scripture itself for the next part.

A. Methodology of Theology

Any good “overview” manual will include an introduction to theology as a science, detailing its structure, method, history and development. But once we have attained an overview of theology, it is worth turning our attention to a serious and more developed work about the science itself.

Many of the errors amongst people of good will, even committed traditionalists, seem to arise from a disordered theological method. For example, we see the Döllingerist tendency of those who treat history as a source of theology, or who turn to arbitrarily chosen saints or theologians in support of pre-conceived theories.

There can be no substitute for starting at the beginning, and spending time understanding the state of various questions in traditional, pre-conciliar theology. A good overview of the methodology will assist us in this study, and in avoiding various pitfalls.

We will only recommend three texts, as this stage of reading is building on topics already addressed in the manuals above. “Methodology” may sound boring, but these texts are very interesting and readable. I have liberally quoted Fenton’s text throughout this series:

Fenton – What is Sacred Theology? (and for UK readers). Originally published as The Concept of Sacred Theology. Internet Archive, and published as What is Sacred Theology? by Cluny Media.

Nicolau – Introduction to Theology. Contained within Sacrae Theologiae Summa Vol. IA. Keep the Faith Publications

Hogan – Clerical Studies (and for UK readers). An overview of the different courses of theology and how to study them. Available online at HathiTrust.

B. Apologetics

Many think that “apologetics” refers to answering Protestant objections. Whole businesses have been established to provide such answers, and this approach meets a real need.

But this approach, which could be called the apology of dogma, arguably does not belong to fundamental theology properly speaking. It would also be a mistake to think that it represents the entirety of what apologetics has to offer.

Rather, we are considering apologetics as the aspect of fundamental theology which sets forth a rational defence of Christ as a divine messenger and saviour. In addition, the advent of modernism and rationalism has made it necessary to defend the ideas of a supernatural, revealed religion itself.

Fenton writes:

“The apologist first shows that there is no contradiction involved in that concept of divine revelation which the Catholic Church predicated of its own dogma. Then it shows the existence and value of true criteria of revelation, notably miracles and prophecies. Finally it demonstrates that Catholic dogma as it is actually presented to mankind is shown to be a true divine message in the light of these criteria.”[4] Fenton, The Concept of Sacred Theology

We could say that this stage deals with what are called the “motives of credibility” for the Catholic Faith. The claims of the Roman Catholic Church herself will be dealt with under ecclesiology. For some examples of works on apologetics and fundamental theology in general:

Fenton – Laying the Foundation (and for UK readers). Originally published as We Stand with Christ, now published by Emmaus Road Publishing.

Nicolau – On Christian Revelation. Contained within Sacrae Theologiae Summa Volume IA. Keep the Faith Publications

Garrigou-Lagrange, On Divine Revelation Vol. I and Vol. II (and for UK readers, Vol. I and Vol II). Trans. by Matthew Minerd.

Van Noort – The True Religion (and for UK readers). This is the first of the three-part series Dogmatic Theology, reprinted by Arouca Press. Unfortunately it can lack depth in places. Available online from Internet Archive.

Walshe – The Principles of Christian Apologetics (and for UK readers). Catholic text for college students dealing with the reasons for Christian revelation, rather than specifically the Catholic Church. Internet Archive.

Walshe – The Principles of Catholic Apologetics (and for UK readers). A truncated adaptation of Garrigou-Lagrange’s de Revelatione (see above) and focusing more on modernism and the idea of a revealed religion than Walshe’s other work. Online at Internet Archive. We have a good edition from Gyan Books).

Glenn – Apologetics (and for UK readers). This is more of a college text. Online at the Catholic Archive.

We must of course also mention the classic text of fundamental theology and apologetics, even if the above texts are more appropriate and accessible for modern students:

St Thomas Aquinas – Summa Contra Gentiles. Aquinas Institute in 2 vols: Vol. I (Books I-II) and Vol. 2 (Books III-IV) and for UK readers here and here. Budget single-volume from Aeterna Press (and for UK readers) and online at iPieta or Aquinas.cc

C. Ecclesiology

Those who are reading the WM Review will likely have an interest in ecclesiology and the constitution of the Church. Fenton writes:

“Under this heading the student of fundamental theology must consider the Catholic Church as the authorized proponent and mistress of all received teaching.”[5] Fenton, The Concept of Sacred Theology

The treatise on the Church considers the qualities and necessary properties of the society founded by Christ, and how it is to be identified amongst the various claimants. It considers the credentials of the Roman Catholic Church, and how it is that we can attain with certainty that she, and no other, is the Church founded by our Lord.

Having established that the Roman Catholic Church is the Church of Christ, ecclesiology then considers her constitution and authority. It considers the Church in her:

Efficient cause – God;

Final cause – glorifying God in Christ and through the salvation of souls;

Material cause – her members;

Formal cause – how and by what these members are bound together.[6]

It considers primarily how the Church teaches, governs and sanctifies – albeit leaving some of the latter to other parts of theology. It also deals with the necessity of the Church for salvation, and her relations with civil society.

This subject naturally deals with the papacy and the magisterium, and concepts such as infallibility and indefectibility. But it is a terrible and unfounded cliché that these manuals of ecclesiology embody an inflated view of the papacy.

On the contrary, anyone who has imbibed myths about the so-called “ultramontanism” and “papolatry” of this period will be amazed at the restraint and cogency of these texts – and when they go further than some today would like, they do so because of extremely strong arguments. Those that come between Vatican I and Vatican II are, in some respects, a gold standard for the subject, enjoying the clarity of the former without any of the confusion of the latter. Further, in so far as these manuals and treatises – approved and used by the Church – agree on points of doctrine, they embody the truth – and we are going to them to learn, not to correct them.

In many ways, the most recent authoritative texts on the Church, there are the following magisterial documents:

Dei Filius (Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith)

Pastor Aeternus (First Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ)

Leo XIII – Satis Cognitum. On the unity of the Church.

Pius XI – Mortalium Animos. On the unicity of the Church.

Pius XII – Mystici Corporis Christi. On the Church, particularly as the mystical body of Christ.

Papal Teachings – The Church (and UK readers – you should be so lucky!) This book is like gold-dust, but try praying a novena to St Peter if you need some help acquiring it. It is a collection of various authoritative texts from the popes on ecclesiology, gathered from written documents and allocutions. It is available online from The Catholic Archive and Internet Archive.

For more detailed and systematic treatments of ecclesiology, there are the following texts:

Bellarmine – On the Church (and for UK readers). Translated by Mr Ryan Grant, Mediatrix Press. Other versions available too. Bellarmine is essential.

Salaverri – On the Church of Christ. Contained within Sacrae Theologiae Summa Volume IB. Keep the Faith Publications

Van Noort – Christ’s Church (and for UK readers). Vol. II of the series discussed above. Internet Archive.

Berry – The Church of Christ (and for UK readers). Excellent single volume manual of ecclesiology. Wipf and Stock.

Anger – The Doctrine of the Mystical Body According to the Principles of St Thomas Aquinas (and for UK readers). Internet Archive.

Billot – Warning: in French! On the Church of Christ. (Vol. I, Vol. II and Vol. III) Billot is one of the most significant theologians of recent times, and was praise by Pius XII in a 1953 allocution to the Gregorian University.[7] The French has been translated from Latin by Fr Gleize SSPX, and is available from Livres en Famille, France. We have included these volumes (and also Gréa’s, below) because of their significance, despite them not being in English. If they were in English, both Billot and Gréa’s texts would be in bold.

Gréa – Warning: in French! The Church and Her Divine Constitution (and for UK readers). NB: this edition says “Vol. I” but it contains both volumes. Available in French from Internet Archive

Fenton – The Church of Christ (and for UK readers). Not a systematic work, but rather contains articles from the American Ecclesiastical Review. Others articles are available as scans from the Bellarmine Forums and The Catholic Archive. Some may also be interested in Fenton’s The Diocesan Priest in the Church of Christ (and for UK readers).

MacLaughlin – The Divine Plan of the Church (and for UK readers). Single-volume apologetics work on the Church, but precise and detailed. Online at Internet Archive.

Finlay – The Church of Christ (and for UK readers). Online at Internet Archive.

We will consider the role of the Fathers and spiritual theology in the next part – but the appendix to this part provides several patristic texts on the Church, along with some spiritual texts which have a particularly ecclesiological focus.

The Roman Pontiff

The position of the Roman Pontiff plays a central role in the treatise on the Church. While some say that “we must diminish the papacy in order to save it,” it is important that we have objective criteria – rather than the intuitions of online personalities – in order to know what we are to believe. Ecclesiology manuals deal with the papacy in a systematic way, but here are some others addressing this topic. All of these texts (and those above) will address the standard Protestant, Gallican and Old Catholic myths about “heretical popes” and so on, which are back in vogue today.

St Robert Bellarmine – Controversies of the Christian Faith. On the Holy Scriptures, Christ and the Roman Pontiff. Translated by Fr Kenneth Baker. (Sometimes available for UK readers). Essential reading for the topic.

St Robert Bellarmine – On the Roman Pontiff (and for UK readers). Again translated by Mr Ryan Grant and published by Mediatrix Press.

Guéranger – The Papal Monarchy (and for UK readers). This text, by the author of the much-loved Liturgical Year, was explicitly approved by Pope Pius IX.

Kenrick – Primacy of the Apostolic See Vindicated (and for UK readers). Fenton describes Archbishop Kenrick as using “a more popular literary style to bring out the same exactness in presentation of Christian doctrine” as scholastic theologians.[8] Online at Internet Archive.

Hergenröther – Anti-Janus (and for UK readers). The response by (later Cardinal) Hergenröther to Dr Döllinger’s historical-theology tract against the papacy. Internet Archive.

Miscellaneous Ecclesiology Issues

Here are some texts which deal with related topics.

Rhodes – The Visible Unity of the Church – Vol. I and Vol. II (and for UK readers here and here). Online here: Vol. I and Vol. II.

The Magisterium

It is important to realise that there are a lot of debates around the terminology and nature of the magisterium. It is not correct to treat this topic as if it was fully established prior to Vatican II. This is a complex area and requires care.

Joy – On the Ordinary and Extraordinary Magisterium: On the Ordinary and Extraordinary Magisterium from Joseph Kleutgen to the Second Vatican Council. This work addresses some of the key lacunae relating to the magisterium. It does take the legitimacy of Vatican II for granted and includes a number of references to post-conciliar theologians, such as Dulles and Sullivan. While this may lead to confusion for some, Joy ‘s work is extremely valuable, both in terms of his charting of the pre-conciliar theological landscape, as well as his own solutions and suggestions in this difficult and not fully-formed area of theology.

Ryder vs. Ward – This was a 19th century controversy over the nature of infallibility and the magisterium. Ryder is somewhat controversial, but many of his considerations are valuable in navigating this territory. It should be noted that Ward himself modified theories which Ryder was criticising in this series of pamphlets. Ward defended himself voluminously in the Dublin Review, but here are some key texts:

Ward – The Authority of Doctrinal Decisions which are Definitions of Faith

Ryder – Idealism in Theology

Ward – A Letter to the Rev. Father Ryder on His Recent Pamphlet

Ryder – A Letter to W. G. Ward, on his theory of Infallible Instruction

Ryder – Postscriptum

Ward – A Brief Summary of the recent controversy on Infallibility; being a reply to Father Ryder on his postscript. (online)

Vacant – The Ordinary Magisterium of the Church and its Organs. Currently being translated by the WM Review from French. Part I available at the link, with subsequent parts linked within.

Sources of Revelation

The “sources of revelation” are Holy Scripture and Tradition. This subject will also be of great interest to readers of this website, dealing as it does with issues relevant to the current crisis (e.g., the magisterium).

Many of the texts on ecclesiology deal with this, and we will leave comments on Holy Scripture itself for the next part – but here are some texts more directly on this topic:

Franzelin – On Divine Tradition (and for UK readers). Translated by Mr Ryan Grant and published by Mediatrix Press.

Van Noort – The Sources of Revelation / Divine Faith (and for UK readers). Vol. III of the series mentioned, dealing with Faith and the rule of faith. Available from Arouca Press.

Garrigou-Langrange – On Faith. Soon to be published by Baronius Press.

Garrigou-Lagrange, On Divine Revelation Vol. I and Vol. II (and for UK readers, Vol. I and Vol II). Trans. by Matthew Minerd.

Walshe – The Principles of Catholic Apologetics (and for UK readers). A truncated adaptation of Garrigou-Lagrange’s de Revelatione. Online at Internet Archive. We have a good edition from Gyan Books.

Billot – The Immutability of Tradition. On revelation and tradition. This is available in French and Spanish. The WM Review is considering working on a translation of this.

Agius – Tradition and the Church (and for UK readers). An introductory text. Internet Archive.

Excursus: “Primary Sources”

Some might criticise the lists above as consisting of mainly of so-called “secondary sources.” There are even persons in the world who betray a disdain for those who wish to follow Bellarmine in ecclesiology and the questions of membership, heretics and offices. We are told that to understand ecclesiology properly, we need to return to so-called “primary sources” – examples given include Turrecremata and Cajetan.

Without discussing whether “primary” and “secondary” are useful terms in this context, I will mention again that the third part does indeed discuss the role of the Fathers and Doctors in learning theology, and some such texts that pertain to ecclesiology are in the appendix. Similarly, the first part of this series listed several magisterial documents – for which the term “primary source” is perhaps more appropriate.

But what of the claim itself? In the context of the criticism, the term “primary sources” appears to refer to the great theologians from history, who have written extensive and profound treatments of the subject. Reading such treatments can of course be edifying and useful: and this is a key reason for learning Latin, as many are untranslated. But we have three observations to make.

Firstly: this is an article about learning theology. One does not learn physics by reading Newton, or astrophysics by picking up texts by Galileo or Copernicus. One studies approved textbooks, which express their subjects, and the received state of their questions, in a systematic way. One enters into a tradition of learning, and one does so at the lowest place: at some point, one may wish to turn to the classic texts mentioned – but not at this point. Manual theology may not be the end, but it is the beginning.

Second: even once we reach that point, do we need to turn to such sources as a matter of course? We do not arbitrarily turn to antiquarianism in the liturgy: why would we do it for theology? We enjoy a certain clarity regarding previously disputed questions, which the great Cajetan, for example, did not. Vatican I and other acts of the magisterium have definitively closed certain questions. It is normal that we wish to benefit from this clarity: and it is found primarily in the textbooks written following Vatican I.

Third, if we must compare St Robert Bellarmine with others on the “heretic pope” question: St Robert decisively refuted Cajetan’s arguments on this question. As Cardinal Billot puts it, “the reasons wherewith Cajetan dismisses his adversaries’ manner of speaking are hardly of any weight.” More importantly: although St Robert treatment focuses on the case of a heretical pope, the principles he basis himself on are not about heresy in an isolated way, but rather membership and the visible unity of the Church. Disputing his conclusions here leads to serious problems with those more fundamental principles.

And we should not need to recall that it is Bellarmine who was canonised, Bellarmine who was made a Doctor of the Church, and Bellarmine whose ecclesiology has been adopted by the Church in Vatican I, Mystici Corporis Christi and elsewhere – and not Cajetan, great though he may be. As Brodrick writes: “At Trent, the Bible and St. Thomas ruled the debates; at the Vatican [I], the Bible, St Thomas and Bellarmine.”[9] Pope Pius XI makes the same point in his elevation of Bellarmine as a Doctor.

The difference in value between Bellarmine and others on these subjects is very great. This is seen all the more clearly when those diverging from his conclusions try to claim him as their authority.

Excursus: The importance of fundamental theology in general

In discharging our duties to study and spread the faith, some of the courses of theology are more important than others. As with natural theology, it is essential that lay Catholics have as secure a grasp of fundamental theology as possible. It may well be rewarding to study branches of so-called “special theology”, such as that of sacraments, or even the liturgy itself. Indeed, we began with overviews of dogmatic theology so that one can grasp the unity and coherence of theology from the outset – and, in due time, one may decide to focus to a greater degree on some specific topic.

Nonetheless, as laymen, we must understand and be able give credible explanations about the existence of God, the divinity of Jesus Christ and the nature of the Catholic Church. We need to be clear what can and cannot happen to the Church – and this clarity comes from approved sources, and not our own intuitions, or piecemeal reading from this or that writer.

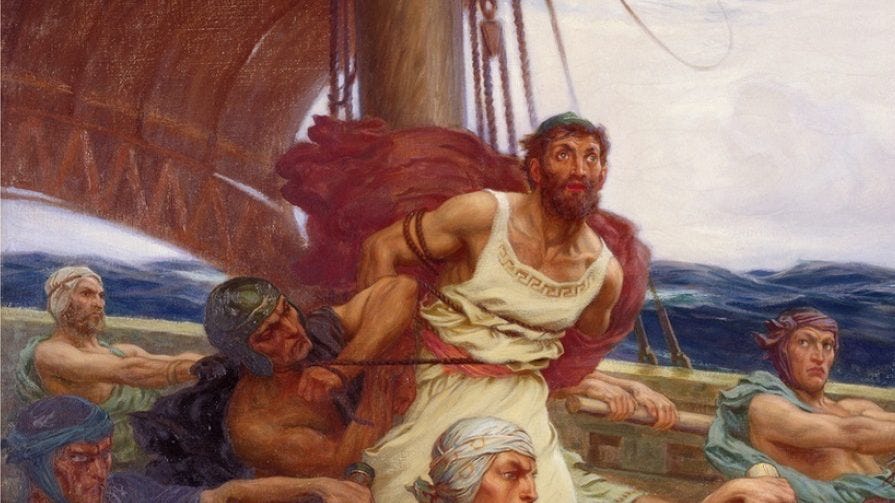

In the Odyssey, Odysseus and his men were compelled to sail past the island of the Sirens, whose singing enchanted all men:

“... That man

who unsuspecting approaches them, and listens to the Sirens

singing, has no prospect of coming home […]

but the Sirens by the melody of their singing enchant him.

They sit in their meadow, but the beach before it is piled with boneheaps

of men now rotted away, and the skins shrivel upon them.”[10]Homer’s Odyssey (and for UK readers) Book XII, 40-46

Odysseus fills his men’s ears with beeswax, to prevent them being tempted by the song: but he has them bind him fast to the mast of his ship, so that he would be able to hear the Sirens’ without diverging from his course.

The depth of our current crisis has caused some to deny things as fundamental as the existence of God. Some do not go so far, but are nonetheless led into heretical and schismatic sects, or to the total abandonment of belief in our Lord Jesus Christ.

A secure grasp of natural theology is protection against atheism; so too, a secure grasp of fundamental theology is a sure protection against these other evils. Proper apologetics will bind a man intellectually to the mast of our Lord Jesus Christ, and to the idea of revealed religion; and proper ecclesiology will bind him to the Roman Catholic Church.

Now, of course, the image from the Odyssey fails – we are not advocating putting ourselves in harm’s way, nor are we romanticising the attraction of error. We are certainly not proposing that anyone study the writings of the Orthodox, Protestants, or other religions: there are excellent reasons for the Index of Forbidden Books, and all old examinations of conscience refer to the danger of bad books. In any case, the systematic ecclesiology texts always include sufficient refutations of the claims of the various false sects.

However, we are in harm’s way already, just because of the world being as it is. All around us, there are persons advocating for this or that error – and even in the privacy of our own intellects, it can be hard to reconcile what we see around us, with the Church’s teaching about herself. This can make some believe that the Church has lost her credibility altogether.

But the Roman Catholic Church is the one true Church of Christ, and Christ is himself our Divine Saviour. Things that were certain before the crisis remain certain now. The difficulties of our time do not somehow disprove the natural proofs of God’s existence by default. The defection of large parts of the Church today do not mean that the Roman Catholic Church herself has defected: nor does it vindicate false sects by default; nor does it disprove the divinity of Christ. We refuse to judge traditional theology by our crisis and re-write it in this darkness: on the contrary, we must let it judge the crisis and provide us with its light.

All this said, we should have great compassion on those who find themselves in this situation of doubt, as they are close to losing the faith. Those who find the crisis too overwhelming, and start looking towards the schismatic Orthodox or elsewhere should step away from modern polemics, podcasts and social media – and return to the fundamentals we have suggested.

Conclusion – the importance of traditional ecclesiology for our current troubles

In the next part we will consider our approach to Holy Scripture, magisterial texts, moral and spiritual theology, the Fathers and Doctors, Canon Law and history. But let us make some remarks on the importance of ecclesiology to Catholics in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Our crisis is ecclesiological, and therefore any theory proposed must also be ecclesiological, and rooted in the tradition represented by these texts. If we have not properly studied this tradition – and polemical post-conciliar writings are not an adequate substitute – then we will not know what we do not know. In such a state, our theories will be built on ignorance, and we are liable to contradict one or another point of doctrine.

As traditionalists, we want to adhere to traditional theology. Theories which rely on distorted texts or historical narratives or novel distinctions are immediately suspect. Theories which require us to reject key points of this traditional theology should be non-starters. This is so, even if we can find isolated proof-texts in the Doctors, Fathers, theologians or even canonists. Our theories should be established from this body of traditional theology, not on theological antiquarianism, other disciplines, or our own imaginations.

Once we study and accept this traditional ecclesiology, we will see that the Church is still here in the world, and is still as she is described in this theology: obscured in many places, but retaining all of her essential properties; and waiting to arise gloriously like the sun on Easter Morning.

And we have the privilege of being members of this Church. What a joy it is to be able to open all these books of from our tradition and to believe what they say.

We may never know about these wonderful things if we do not read and accept Roman ecclesiology.

Appendix I: Spiritual works for those interested in ecclesiology

Guéranger’s work is the ultimate synthesis of ecclesiology and spiritual reading; it takes on whole new meanings and beauty after certain obscured truths about the Church are accepted. Here it is, along with some other suggested titles.

Guéranger – The Liturgical Year, 15 vols. See here for UK readers – although you may need to just order from the US link. A great edition was from St Bonaventure Press, (check here for availability) but this is currently out of print. It is still available from Loreto Publications in hardback and paperback editions. Available on the iPieta app and currently being posted daily online.

Boylan – This Tremendous Lover (and for UK readers). Baronius Press

Clérissac – The Mystery of the Church (and for UK readers). Online at the Bellarmine Forums.

Benson – Christ in the Church (and for UK readers). Online at Internet Archive.

Leen – The True Vine (and for UK readers). Online at Internet Archive.

Marmion – Christ the Life of the Soul (and for UK readers). Online Internet Archive.

Appendix II: Fathers and Doctors

As mentioned in the text, I will address this in the next part. In the meantime, here are some texts with a focus on ecclesiology.

The Faith of Catholics, by Berington, Kirk and Waterworth, is a three-volume collection of patristic texts on various subjects. Vol. I and the start of Vol. II deal particularly with the Church and the Papacy. Available here: Vol I, Vol. II, and Vol. III (and for UK readers, Vol I, Vol. II, and Vol. III). Internet Archive (Vol. I, Vol. II and Vol. III) and as print-on-demand.

St Augustine. Most of his works are available online at New Advent.

On Baptism Against the Donatists is of relevance (and for UK readers).

On the Unity of the Church, available as an anonymous translation at Christian Resources.

St Cyprian – On the Unity of the Church (and for UK readers). Available in The Lapsed / The Unity of the Catholic Church, (Ancient Christian Writers series) trans. by Maurice Bevenot and published by Paulist Press, or online (NB: this is a transcription of an old translation, and we are not clear of the provenance of the website itself.)

St Vincent of Lerins – Commonitorium Against Heresies (and for UK readers). Published by Tradibooks, and online at New Advent.

St Francis de Sales – The Catholic Controversy (and for UK readers). Online at Internet Archive.

St Alphonsus – The History of Heresies (and for UK readers). Online at Internet Archive.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter and Telegram:

[1] We have compiled such notes from the Bellarmine Forums with the permission of the owner. Here are the three main inspirations: Learning Sacred Doctrine; Theology Manuals in English; and How to Form a Catholic Mind.

[2] Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton, The Concept of Sacred Theology, published as What is Sacred Theology? Cluny Media, Providence RI, 2018. (UK readers) p 118

[3] Fenton 222

[4] Fenton 223.

[5] Fenton 224

[6] Fenton 225

[7] “Let us gladly recall our teachers such as Louis Billot, to name one, who, with spiritual distinction and intellectual acumen, incited us to venerate the sacred studies and love the dignity of the priesthood.” Pius XII, quoted by Fr Dominique Bourmaud in An Anti-Liberal Theologian, The Angelus May 2016, available at http://www.angelusonline.org/index.php?section=articles&subsection=show_article&article_id=3845

[8] Fenton 149

[9] Fr. James Broderick SJ, St. Robert Bellarmine, Longmans, London, 1950, Vol. I, p.188.

[10] Homer, The Odyssey of Homer, trans. Lattimore, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, London 2007. Book XII, 40-46

[11] Roberto de Mattei, The Second Vatican Council (an unwritten story) (and for UK readers), Loreto Publications, Fitzwilliam NH, 2012, p 440.

[12] Mgr Joseph Clifford Fenton, ‘Father Journet’s Concept of the Church’ in the American Ecclesiastical Review, CXXVII No. 5, November 1952. Available at: http://www.strobertbellarmine.net/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=649