'How long will we still have valid bishops?' Abbé Mouraux answers

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre's friend and collaborator Abbé Henri Mouraux answers: 'Not long,' at least in the Latin-rite, among those who use the new sacramental rites—and it's by their own admission!

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre's friend and collaborator Abbé Henri Mouraux answers: 'Not long,' at least in the Latin-rite, among those who use the new sacramental rites—and it's by their own admission!

Editors’ Notes

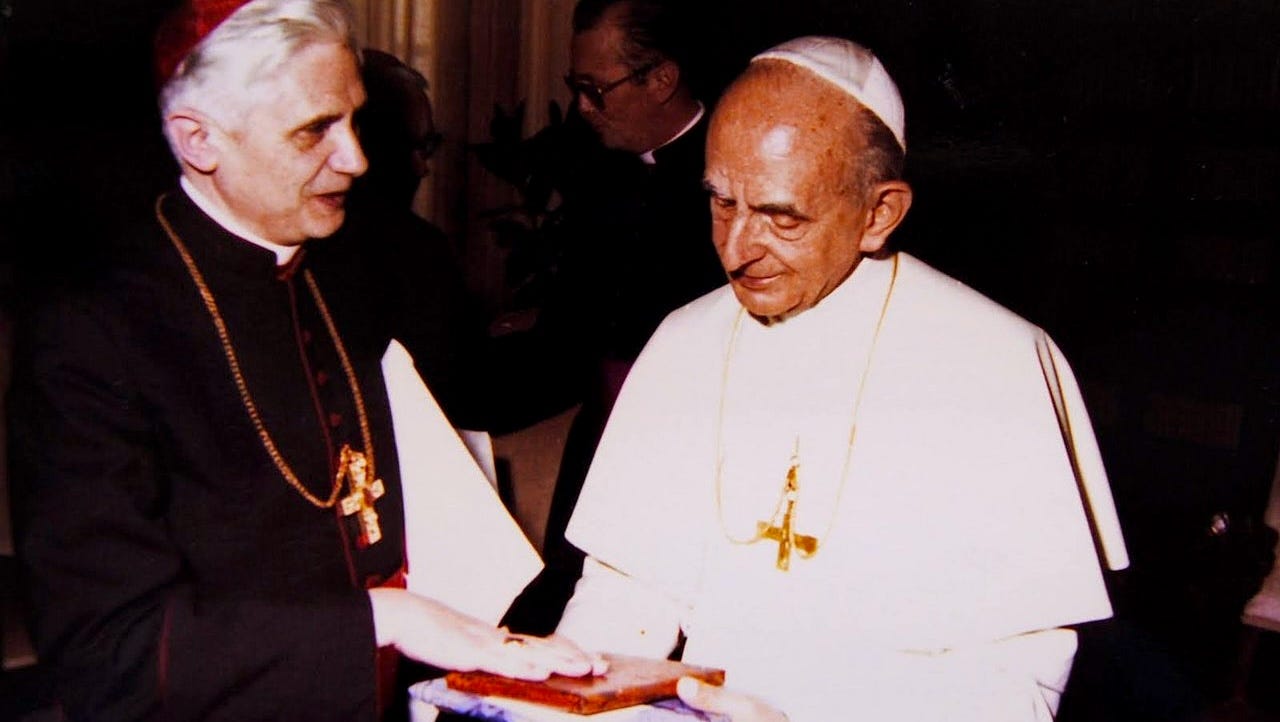

Abbé Henri Mouraux and Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre

As we have mentioned a few times now…

Abbé Henri Mouraux was a longtime friend and collaborator with Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. In the sermon for Mouraux’s golden anniversary of his priestly ordination, Lefebvre praised his faith and faithfulness, boldness and courage, and his refusal to cower under accusations of “disobedience.”

But what might surprise some is that Mouraux openly held that the post-conciliar claimants to the papacy were not true popes.

Mouraux was responsible for the bulletin Bonum Certamen, in which he advanced controversial theses, such as the invalidity or doubtfulness of the new rites of Holy Orders.

Our last translation was Bonum Certamen No. 58, on the new rite of priestly ordination. What follows is a translation of Bonum Certamen No. 59 (Sep-Oct 1981), which is on the new rite of episcopal consecration.

Mouraux’s treatment of the new rite of episcopal consecration

In this edition, Mouraux analyses the new rite of episcopal “ordination” (as the rite refers to itself), and the comments of those who use it.

In this article, Mouraux considers again the comments of those who were using the new rites and explicitly disclaiming their sacramental efficacy, based on their own lack of intention to create sacrificing priests. Coupled with the drastic changes to doctrine expressed in the rites, Mouraux argues that the new rites create the same “defect of intention” which Pope Leo XIII noted in Apostolicae Curae, regarding Anglican orders.

Building on the previous article regarding the problems with the new rite of priestly ordination, he discusses the problematic nature of “per saltum” consecrations—viz., consecration to the episcopate of a man who is not actually a priest.

He also provides some shocking comments used by conciliar bishops, which would almost be amusing were it not for their irreverence.

However, as we are publishing this translation primarily for its historical interest, Mouraux’ article is unusual in two respects.

Discrepancy with Pope Pius XII

First, Mouraux refers to the sacramental form as delineated in the particular missal that he had before him, without referring to Pope Pius XII’s 1954 Apostolic Constitution Sacramentum Ordinis. The prayer to which Mouraux refers appears a little earlier in the rite than the preface designated by Pius XII.1

This discrepancy is explained by the fact that it was not clear, prior to Pius XII, which was the actual form; and in any case, Pius XII only settled the question for the future, without regard for what the form had been previously.

As such, Mouraux does not refer at all to the prayer with which we are most familiar today:

“Comple in Sacerdote tuo ministerii tui summam, et ornamentis totius glorificationis instructum coelestis unguenti rore santifica.”

[“Perfect in Thy priest the fullness of thy ministry and, clothing him in all the ornaments of spiritual glorification, sanctify him with the Heavenly anointing.”]2

This is sometimes called “the essential form,” although we should note that Pius XII actually phrases himself somewhat differently:

The form consists of the words of the “Preface,” of which the following are essential and therefore required for validity: “Comple in Sacerdote tuo, etc.”

It does seem odd that Mouraux does not refer to this Apostolic Constitution.

Nonetheless, his general points stand even in spite of this omission.

Discrepancy with Paul VI

The second unusual feature is similar to the first. In the 1968 Apostolic Constitution promulgating the new rite of episcopal consecration—or “ordination” as the Constitution calls it—Paul VI uses the same language as Pius XII:

“Finally, in the Ordination of a Bishop, the matter is the imposition of hands, performed in silence by the consecrating Bishops, or at least by the principal Consecrator, over the head of the Bishop-elect before the prayer of consecration.

“The form consists of the words of the same prayer of consecration, of which the following pertain to the essence of the rite, and hence are required for validity:

“‘And now pour forth on this chosen one that power which is from you, the governing Spirit, whom you gave to your beloved Son Jesus Christ, whom be gave to the holy Apostles, who founded the Church in every place as your sanctuary, unto the glory and unending praise of your name.”

(Et nunc effunde super hunc electum eam virtutem, quae a te est, Spiritum principalem, quem dedisti dilecto Filio Tuo Jesu Christo, quem ipse donavit sanctis Apostolis, qui constituerunt Ecclesiam per singula loca, ut sanctuarium tuum, in gloriam et laudem indeficientem nominis tui.)3

Mouraux does not refer to these words, which Paul VI says “pertain to the essence of the rite.”4 He only refers to the last prayer of the Preface.

However, as with the point above: although this is unusual, it does not change the substance of Mouraux’s argument.

Further, we are presenting this text solely for its historical interest, in that it shows the sorts of arguments current in the 1980s, amongst those with warm relations with groups like the SSPX.

The actual state of the question

The WM Review has refrained from arguing for a hard conclusion of invalidity of the new and reformed/deformed rites.

Nonetheless, one does not have to accept arguments for invalidity personally and fully in order to acknowledge that they give rise to a reasonable and prudent doubt about the rite of priestly ordination itself, and every single use of it. This is especially so given the number of different arguments converging on this conclusion.

This doubt is, in fact, not resolvable by studies or investigations: it is only resolvable by conditional repetition of the sacraments in question. As such this route of conditional repetition has frequently been followed by traditional groups since Vatican II.

This is justifiable on theological, practical and pastoral grounds. It is also justified on “customary” or “traditional” grounds, in that so many men involved in the traditionalist response to Vatican II—including Archbishop Lefebvre, the recently departed Bishop Tissier de Mallerais, Fr Álvaro Calderón and many more—have held to these conclusions.

This route of conditional ordination is also justifiable on the grounds of natural justice: it would place those many men in an inescapable difficulty of conscience to impose a conclusion of validity upon them, even solely in practice. This is especially so, because even if one believes for oneself that the arguments have been refuted, it is the role of the Church alone to resolve such evidently open questions for all, and not private scholars or superiors of congregations.

Following this article, there is our usual reassurance for individuals ordained in these new rites, or who might be troubled by the ideas expressed.

Will we still have validly consecrated bishops for long?

Bonum Certamen, No. 59, Nov-Dec 1981

Translated by The WM Review, with additional line breaks for ease of reading.

The Catholic Bishop

There are seven sacraments; and there are only seven. This is a matter of faith, by Canon I of the Seventh Session of the Council of Trent.

Therefore, episcopal consecration is not a sacrament distinct from priestly ordination: it is its full blossoming. Consequently, the primary condition to become a bishop is to have validly received priestly ordination.

According to the Pontifical to which I am referring—the edition of Benedict XIV—the episcopate is conferred in the same manner as the first degree of priesthood, through what is termed matter and form (see the previous Bonum Certamen (n. 58).

The matter, in this context, is the laying on of the consecrating bishop’s hand; and the form, the formula:

“Episcopum oportet judicare, interpretari, consecrare, ordinare, offerre, baptizare, confirmare”

(“The bishop must judge, interpret, ordain, consecrate, offer, baptise, confirm”).

In this formula, all the spiritual powers of the bishop are summarised:

To be the judge of his diocesan subjects in matters of faith

To explain the Christian Law

To consecrate

To ordain priests

To offer the sacrifice

To baptise

To confirm.

No mention is made of the power of jurisdiction, as this does not derive from consecration, but flows from the mission of Christ given to the teaching Church.

The Conciliar Bishop

We demonstrated in Bonum Certamen 58 that there is a very grave probability—if not nearly a certainty—that those ordained by French bishops since 1968 may not be priests.

Consequently, those consecrated as bishops from among these priests are very probably merely laymen, possessing no more sacerdotal power than episcopal power.

As for priests consecrated as bishops under the conciliar rite, even if they were previously validly ordained (thus, prior to 1968), their episcopal consecration is gravely doubtful, if not invalid.

This is a members-only post for those who support us with monthly or annual subscriptions.

Our work takes a lot of time and energy. Please consider subscribing if you like it.

Here’s why you should take out a membership of The WM Review today:

Help us continue building the case for a restrained, theological approach to the crisis in the Church

Eclectic and sometimes eccentric variety of content

Provide FREE membership to clergy/seminarians (subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

A small monthly membership really helps us keep The WM Review going. Can you chip in today?

In the meantime, you might enjoy this: