Are Novus Ordo sacraments valid—and how would we know?

The wholesale destruction and reconstruction of the Catholic religion at Vatican II included changes to every sacramental rite of the Latin Church. Can we be sure these Novus Ordo rites are valid?

The wholesale destruction and reconstruction of the Catholic religion at Vatican II included changes to every sacramental rite of the Latin Church. Can we be sure these Novus Ordo rites are valid?

Introduction

The following is a translation of an article by Abbé Hervé Belmont. It is about the validity of the reformed rites of the sacraments.

The position it takes is modest, and different from some other arguments and conclusions proposed by traditionalists. It has much to commend it for those who are unconvinced by more categorical arguments for invalidity.

Fr Belmont was ordained by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, and is located in Saint-Maixant, France. His articles and essays are available in French at Quicumque.com, and we are very happy to have his permission to publish some of them in translation here.

We are sharing it, not as a statement of The WM Review's position, but as an additional voice to the discussion. We welcome any attempts to refute his argumentation.

There are some of our own explanatory notes following the article.

The Validity of the New Sacraments

Fr Hervé Belmont

Translated and headings added by The WM Review

Of all the novelties introduced by Vatican II or in its wake, the liturgical reform – and the reform of the sacraments which is at its heart – has been the most visible and the most familiar, encountered daily. What has been perceived above all is the massive desacralisation, the omnipresent Protestantisation, the ridicule taking possession of the sanctuary.

But there is a more fundamental aspect, more insidious because it is not directly discernible: the sacramental validity of the new rites. This aspect is far more distressing and has greater consequences than the spectacle of a vicar at a singalong session.

To see clearly, to be guided with certainty and wisdom through the range of theoretical and practical possibilities, it is necessary to place the problem in its true light: the nature of the sacraments and the principles which govern them.

The Facts

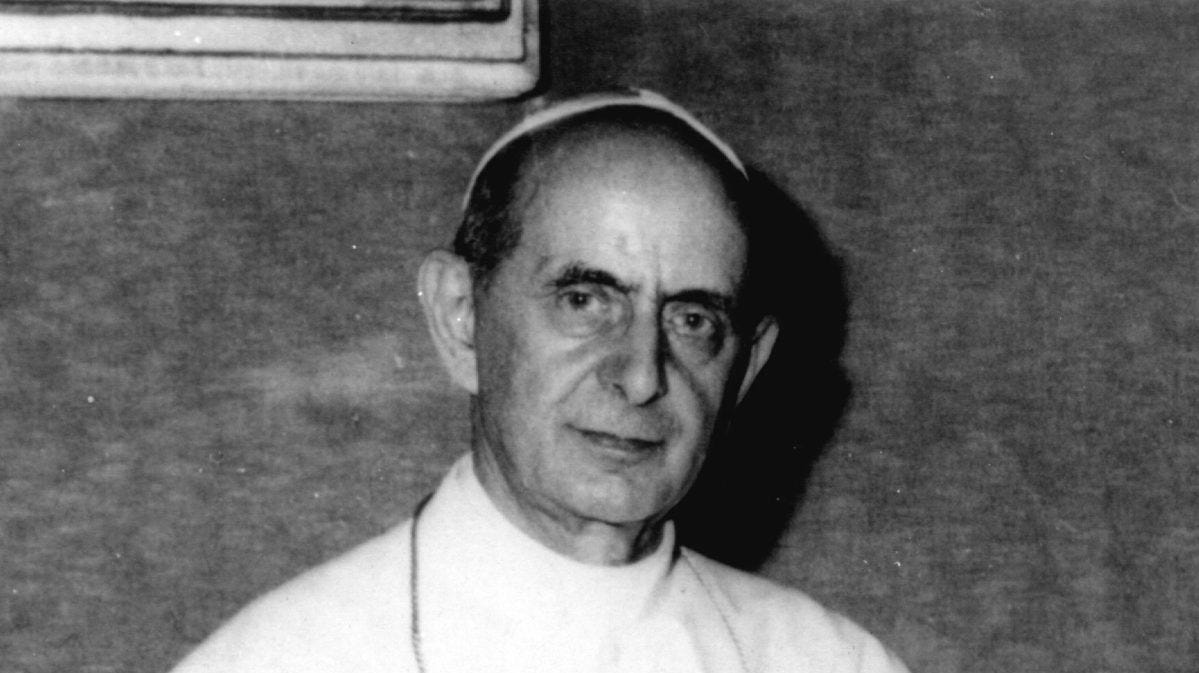

In accordance with the stipulations of Vatican II,1 Paul VI initiated the reform of all the sacramental rites, and promulgated the various elements between 1968 and 1973.2

This reform concerns the essence of the sacraments, and the Protestant influence is constantly felt here; we are therefore justified in asking whether the rites introduced by Paul VI are indeed the instruments of Jesus Christ, the channels through which he gives sacramental grace.

Indefectibility

This question of the validity of the new sacramental rites cannot and must not be separated from two other inescapably related questions:

That of the conformity of the rites to the Catholic faith

That of the reality of the Authority which promulgated them.

For in effect:

If these rites come from the true Authority of the Church, it is impossible for them to be either at variance with the faith or invalid: the assistance of the Holy Ghost guarantees both their agreement with the faith and the efficacy of grace

If they are not in conformity with the Catholic faith, then it is impossible that they come from the legitimate Authority, which cannot give the Church any bad law3 or despicable rite4

If, in essence, these rites are not in accord with the Catholic faith, then they cannot be valid: it is the faith of the Church which makes the sacramental signs instruments of Jesus Christ for the gift of His grace5

If they do not come from the Authority of the Church, then there is no guarantee of their validity, which can only be known in faith and therefore by the Church’s witness.

Only the Church will be able to decide the question categorically and definitively. In the meantime, however, it is necessary to know what we should make of it all – that is, from the sole point of view of validity; since the witness of faith is opposed to active participation in these rites.

But, once these rites have been performed, what can we know about them?

Implications

If one admits, with good reason, that the liturgical reform is neither the fruit nor the expression of the faith of the Church, one must admit by this very fact that this reform does not come from the Church, and that Paul VI was deprived of pontifical authority. (This can also be established from the totality of his acts, which do not produce the good of the Church; or from his teaching of religious freedom.)

Since these rites do not come from the Church, it is impossible to assert that the minister who uses them (whoever he may be and whatever his intentions) does in fact intend to do what the Church does. His real and effective intention is precisely to use these rites – and these rites are not what the Church does.

Doubt and Practical Conclusions

One cannot, therefore, affirm the validity of the rites of the sacraments of which an essential element – the matter or the form – has been changed (Confirmation, Eucharist, Extreme Unction, Order): one can only remain in doubt about them.

For the other three sacraments (Baptism, Penance and Marriage) whose form has not changed: there has been, in the proper sense, no new promulgation of the essential part – and therefore, a priori, there is no need to question their validity [Editors: see below comments about Doubtful Baptisms]

For the four whose form has been modified, there is – at the very least – a “legal doubt,” due to the absence of the supernatural and necessary guarantee of the Church.

But since the sacramental life – no more than the life of faith – cannot accommodate doubt, they must in practice be held invalid.

Source: l’Abbé Belmont’s website Quicumque – reprinted with permission

Editors Notes

As this is a short article, it is worth breaking the points down and explaining them in greater detail.

Indefectibility and infallibility

Fr Belmont starts with the fact of Church’s indefectibility.

This indefectibility does not simply mean that the Church cannot give us liturgical rites which are sacramentally invalid. It also means that she cannot give us liturgical rites which are harmful or at variance with the faith.

This is a commonplace of the Church’s theology, and is discussed in many manuals of ecclesiology (more commonly treated under the heading of ‘the secondary object of infallibility’).

It is also established in Fr Belmont’s footnotes, and in the article which he has published on the topic:

How does all this apply to the Novus Ordo liturgy and its accompanying sacramental rites?

The harmfulness of the Novus Ordo rites

Most traditionalists agree that the Novus Ordo rite is indeed harmful and at variance with the faith.

Many have concluded that the Novus Ordo is bad in itself: this, for example, is the thesis argued by Fr Jean-Michel Gleize SSPX in a 2021 edition of Courrier de Rome:

“The Brief Critical Study considers this departure from the perspective of the four causes: material (the Real Presence), formal (the sacrificial nature), final (the propitiatory purpose), and efficient (the priest's role).

“This serious shortcoming leads to the conclusion that the new rite is ‘in itself bad’ and prevents viewing this new rite as legitimate and even allows doubt about the validity of celebrations in more than one case.”6 [Emphasis added]

The ‘Declaration of Fidelity to the Positions of the Priestly Society of Saint Pius X’ also states as follows:

“I grant that Masses celebrated according to the new rite are not all invalid. However, considering the bad translations of the Novus Ordo Missae, its ambiguity favouring it being interpreted in a Protestant sense, and the plurality of ways in which it can be celebrated, I recognise that the danger of invalidity is very great.

“I affirm that the new rite of Mass does not, it is true, formulate any heresy in an explicit manner, but that it is ‘both as a whole and in its details, a striking departure from the Catholic theology of the Mass’, and that for this reason the new rite is in itself bad.

“That is why I shall never celebrate Holy Mass according to this new rite, even if I am threatened with ecclesiastical sanctions; and I shall never advise anyone in a positive manner to take an active part in such a Mass.”7 [Emphasis added]

In other words, there is a fairly common traditionalist observation of the situation. Further, the central idea mentioned above – that “the new rite is in itself bad” – seems also to apply to the various other post-conciliar liturgical rites, which were also offered to the world by the same source, coming from the same “authority” and basically all in the same way – and are subject to similar critiques.

Therefore, if we have no grounds to say that the Novus Ordo rite came from the Church’s authority, then we have no grounds for saying the other reformed rites did either.

However, if we are to hold that these rites are bad in themselves, it is impossible to affirm that they have come to us from the Church.

Archbishop Lefebvre himself, when under pressure from the CDF, also refused to concede that the Novus Ordo came from the Church, as discussed below:

He also wrote directly in 1980 of the various novelties, including those pertaining to the sacraments:

“These novelties do not come from the Holy Ghost, nor from His Church, but from those who are imbued with the spirit of Modernism, and with all the errors which convey this spirit, condemned with so much courage and energy by St. Pius X.”8

A few lines later, in the same letter, he referred to these sacraments as “doubtful”:

“The Church cannot content herself with doubtful sacraments nor with ambiguous teaching. Those who have introduced these doubts and this ambiguity are not disciples of the Church.”9

The 2001 SSPX study on the liturgy The Problem of the Liturgical Reform also directly asserts that the reform did not come from the Church:

“Equally, one cannot say that the rite of Mass resulting from the reform of 1969 is that of the Church, even if it was conceived by churchmen.”10

Anyone who would concede this for the Novus Ordo but not the other sacraments is invited to explain the basis of this distinction.

In any case, this was also the position held by other early (and contemporary) traditionalists, and this is the reason why there have been arguments based around defects with the promulgation of the rite.

Claiming that the Novus Ordo did not come from the Church can lead to a perplexing problem – because it certainly appears to have done so. There would have to have been some sort of issue, such that it did not come from the Church, despite appearances to the contrary.

How, then, to explain that these apparent rites of the Church are no such thing?

Attempts to explain why the Novus Ordo rites did not come from the Church

As mentioned, some have tried to explain this by arguing that the Novus Ordo Mass was never properly promulgated.

First, this does not really address the problems of the other sacramental rites.

Regardless: the passing of over 60 years makes arguments based on defective promulgation harder to mount: after all, Canon Law holds that a “custom beyond the law,” if observed by a community for a continuous period of forty years, becomes law.11

There can be no doubt that the putative authorities have given (at least) tacit approval to the Novus Ordo due to its apparently customary use (cf. canons 25-30). Thus, even if these rites were promulgated invalidly, they would seem to have attained the force of law and the status of universal disciplines through customary use.

As such, the arguments based on non-promulgation are insufficient, in themselves, to explain how the Novus Ordo Mass is not a rite of the Church or "from the Church."

Further, such arguments would not prove the validity of these rites. They are a way of “getting the Church off the hook” for the harmful and heterodox rites; but if the Church is not responsible for them, then it is not clear why we should assume that they nonetheless still enjoy the guarantees given to the Church by Christ.

Questions of authority and the papacy

The Church’s authority is what gives us the guarantee both of the validity of a sacramental rite and that this rite (and its liturgical surroundings) are in accordance with the faith, and safe and salutary to use. There is no principle of Catholic theology which says that the Church may promulgate a wicked, harmful or erroneous rite, so long as it is still valid.

Thus, it is not possible to critique the reformed post-conciliar rites as harmful, non-Catholic or embodying error whilst presuming, a priori and in principle, that they must nonetheless be valid, on the grounds of the Church’s indefectibility or authority.

If these rites are harmful, then the “authority” which gave them to us was, for whatever reason, not the authority of the Church. There are no good reasons based on the authority of the Church (which is not engaged here) to presume validity.

However, as Fr Belmont mentions, the fact that these rites which cannot have come from the Church’s authority nonetheless definitely came from Paul VI and post-conciliar Vatican apparatus, we cannot escape the conclusion, further down thrle line, that the Conciliar (now ‘Conciliar-Synodal’) Church is not the Catholic Church.

While this line of argument points inexorably towards the non-papacy of Paul VI and his successors, it is important to note that the overall thrust of this piece is not a sedevacantist argument.

It is an argument based on the correct observations of traditionalists and groups like the SSPX, read in light of traditional ecclesiology.

Unwarranted presumptions of validity

Another way of putting the problem is this: if the reformed rites suffered a change in an essential part of the rite – which Fr Belmont defines as either the matter or form of the sacrament – and if these rites do not come from the Church’s authority, then we have no prima facie grounds for presuming that they are valid.

Such rites may well be valid in fact, but (as they say) who are we to judge? Who are we to judge, especially if an essential (the matter or form) has been changed?

We would have to study each changed form, and our conclusions may only be as probable as the arguments.

As a recent historical example of even high authorities not deeming it fitting to judge such questions, we could consider the words of the embattled English bishops in 1898. They wrote an eloquent Vindication of Leo XIII’s bull on Anglican orders and liturgical changes. They considered the idea of validity and liturgical change from the same angle we are explaining here:

"[The idea that local churches were] permitted to subtract prayers and ceremonies in previous use, and even to remodel the existing rites in the most drastic manner, is a proposition for which we know of no historical foundation, and which appears to us absolutely incredible."12

And why was this important?

"[…] Immemorial usage, whether or not it has in the course of ages incorporated superfluous accretions, must, in the estimation of those who believe in a divinely guarded, visible Church, at least have retained whatever is necessary; so that in adhering rigidly to the rite handed down to us we can always feel secure; whereas, if we omit or change anything, we may perhaps be abandoning just that element which is essential."13

The burden of proof is on those who want to argue that these rites are harmful to the faith, but nonetheless still valid.

In any case, once someone starts trying to prove that the reformed rites fulfil the requirements of Catholic sacramental theology on intrinsic grounds, he is already starting to lose the argument. Such attempts implicitly concede that "the authority of the Church" is insufficient to guarantee these rites. For the reasons discussed, this cannot be answered with reference to the “authority” of the Conciliar-Synodal Church.

Further, those making these arguments are presuming to enter a complex branch of theology in which, in most cases, the advocate will be out of his depth. This inevitably leads to simplifications and overstatements.

Even if someone is personally convinced of such arguments for themselves, we all need to recognise the status of such a conclusion – it is a private judgment, perhaps binding on the one reaches it, but not on anyone else.

It is for the Church herself to impose such certainty, and with a matter like this, it would be unjust for such a judgment to be imposed on others, explicitly or implicitly.

This is to say nothing about defects of intention amongst Novus Ordo ministers – another real problem, but mostly outside the scope of this piece.

In short, if one is saying that the New Mass is bad in itself or harmful to the faith, one is already walking down this road. Thus we arrive at a position of at least doubt about the four sacramental rites whose essentials were changed.

Analysis of the argument - and its consequences

Fr Belmont's argument is effective, because the burden of proof for establishing positive doubt is much lower than for establishing positive invalidity; and it bypasses the psychological barrier of having to assume that all of one’s previous sacraments were invalid.

And yet the conclusion is the same: in practice, we must treat these sacramental rites as invalid and avoid them.

This is because, aside from our duty to avoid the sacramental rites which have not come from the Church, we are not entitled to administer or receive the sacraments under circumstances when they are merely “probably” valid.

If we were to receive the sacraments under such circumstances, we would essentially be acting in a doubtful conscience, willingly either receiving a sacrament or merely simulating one – the latter of which is a sacrilege. Such exposure of a sacrament to the danger of invalidity is impermissible, as is the reception of a sacrament – although we should take into account the differences between positive and negative doubts.14

For these reasons, there would seem to be no need to argue that these sacraments are invalid. If these rites are bad or harmful in themselves, then it would seem that they are doubtful until such point that the Church decides the question, or certainty is attained some other way (if possible).

By contrast, the arguments purporting to prove the invalidity of the the reformed rites of Holy Orders may go further than is necessary for reaching the same practical result. Such arguments, due to their higher burden of proof, serve as a larger and easier target for attack by the proponents of their validity.

Repetition and Conditional Sacraments

It is well known that absolute repetition of Confirmation or Holy Orders is unlawful (and even sacrilegious) without a clear reason for concluding invalidity. The same applies to Baptism.

However, when there is just cause, conditional repetition protects against this danger whilst ensuring that moral certainty is attained. Canon law states:

Canon 732

§ 1. The Sacraments of baptism, confirmation, and orders, which imprint a character, cannot be repeated.

§ 2. But if a prudent doubt exists about whether really and validly these [Sacraments] were conferred, they are to be conferred again under condition.

The doubts in our day about these Novus Ordo sacraments are by no means groundless or scrupulous – they are based on a prudent fear, for serious reasons – not least the spectacle of the wholesale religious revolution we have seen over the last 60 years.

According to the moralists McHugh and Callan, under such circumstances, it is gravely obligatory to repeat the “necessary or more important” sacraments (including Baptism and Holy Orders) under such circumstances, at least conditionally. It is also more or less obligatory for the other sacraments when charity, justice and religion call for it:

Repetition of a Sacrament on Account of Invalid Administration.

(a) This is unlawful when the fear of invalidity is groundless and foolish; for it is seriously disrespectful to a Sacrament and disedifying to others to repeat the rite without reason. But scrupulous persons are sometimes free of grave sin, since they mean well in repeating and are not accountable for their fears.

(b) This is lawful but not obligatory when there is a prudent misgiving about a useful Sacrament (Confirmation, Matrimony, anointing of one who is conscious); also when there is a slight reason of law or fact for fear about a necessary or more important Sacrament (Baptism, Orders, absolution of a dying person, anointing of an unconscious person, consecration of the Eucharist). For the Sacraments are for men. But if only a small loss or an unlikely loss will be caused by their non-repetition, the duty of repeating them cannot be insisted on.

(c) This is gravely obligatory when there is a prudent fear about a necessary or more important Sacrament; it is gravely or lightly obligatory (to be determined in each case) when there is a well-founded fear about a useful Sacrament, if charity, justice or religion calls for repetition and the inconvenience will not be too great. In Matrimony the alternate methods of convalidation or sanation may be used as the case demands. Again, the Sacraments are for men, and hence, if man will likely be subjected to a notable loss by the minister’s neglect of repetition, the duty of repetition is clear.15

Let’s note that these two moralists also say that it is lawful even if the doubt were to be construed as being rooted on only “a slight reason of law or fact” regarding a necessary or more important Sacraments.

Regarding the “loss” caused by the non-repetition of such sacraments subject only to “slight reason of law or fact,” it is a fact that rightly or wrong, many of the traditionalist laity have concerns about the validity of these new rites, and will struggle to accept assertions of validity, no matter how they have been investigated and proved. Because of this, the imposition of men ordained in the Novus Ordo rites has historically caused extreme difficulties of conscience and various untoward consequences.

Even those who are relatively convinced that the Novus Ordo rites are valid must surely concede that there is at least a “slight reason” for concern, as McHugh and Callan put it (although this is a dramatic understatement in our situation).

Therefore, it would seem necessary for those who have been ordained in the reformed rites to seek a repetition of these sacraments under condition – this being either gravely necessary in itself, or at the very least (depending on one's position) legitimate for the sake of peace and the good of souls.

This, as is well known, is the course of action which has often been followed throughout the post-conciliar period.

Conclusion

The valid reception of the sacraments is essential to the Catholic life. Even those who think that the reasons for doubting the Novus Ordo rites are trivial, must surely realise that their opinion is not shared by everyone. They must surely also realise that the Church has provided us with an easy remedy in the conditional conferral of the sacraments, which provides a means of ensuring peace and moral certainty in such circumstances.

One slight point of departure we may have with the way Fr Belmont expresses something is this: he says that there is no need to question the validity of Baptism, as the form was not changed.

While this is correct, we do suggest that readers also read our essay on Doubtful Baptisms, which addresses the situation of baptisms administered according to the reformed rite, and other related circumstances.

As mentioned at the start, this does not necessarily represent the “position of The WM Review,” but the argument seem compelling – attempts to refute it are welcome.

Nonetheless, all this goes to show that to preserve sacramental integrity, safeguard the common good, and secure peace of conscience, it is essential that all traditionalist groups systematically implement the conditional ordination/consecration of clerics whose orders depend on the validity of the Novus Ordo rites.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone. If you have benefitted from our content please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material!

Thank you!

Read Next:

Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of 4 December 1963, nn. 50, 66, 71, 72, 75, 76 & 77

Order: Apostolic Constitution Pontificalis Romani of 18 June 1968; AAS 1968 pp. 369-373.

Eucharist: Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum of 3 April 1969; AAS 1969 pp. 217-222.

Marriage: Decree of 19 March 1969; Notitiæ (bulletin of the Congregation for Divine Worship) 1969 pp. 203.

Baptism: Decree of 15 May 1969; AAS 1969 p. 548. 548.

Confirmation: Apostolic Constitution Divinæ consortium naturæ of 15 August 1971; AAS 1971 pp. 657-664.

Extreme Unction: Apostolic Constitution Sacram Unctionem infirmorum of 30 November 1972; AAS 1973 pp. 5-9.

Penance: Decree of 2 December 1973; AAS 1974 pp. 172-173

Pope Pius VI condemns – as “false, rash, scandalous, pernicious, offensive to pious ears, injurious to the Church and to the Spirit of God who leads her, at the very least erroneous” – a proposal of the Synod of Pistoia on the discipline of the Church on this ground: “As if the Church, which is governed by the Spirit of God, could constitute a discipline, not only useless and too heavy for Christian liberty to bear, but also dangerous, harmful, and leading to superstition and materialism” (Denz. 1578).

Popes Gregory XVI (Quo Graviora of 4 October 1833) and Leo XIII (Testem benevolentiæ of 22 January 1899) explicitly refer to this condemnation.

“If anyone says that the rites received and approved by the Catholic Church, in use in the solemn administration of the sacraments, may be despised, or omitted without sin at the pleasure of the ministers; or that any pastor may, in his church, change them into other new ones, let him be anathema.’

Council of Trent, 13th Canon of Session vii, Denz. 856

“The efficacy – or virtue – of the sacraments is derived from three things: from the divine institution, which is its principal agent; from the passion of Christ, which is its first meritorious cause; and from the faith of the Church, which brings the instrument into continuity with the principal agent.” (Emphasis added)

St. Thomas Aquinas, IV Sent. d. i q. i a. 4 sol. 3.

Fr Jean-Michel Gleize SSPX, ‘Le Nouvel Ordo Missae de Paul VI – Est-il mauvais en lui-même ?’ Courrier de Rome, November 2021.

SSPX, Statutes, Rules and Ceremonies of the Priestly Society of Saint Pius X, 2022. p 188

Archbishop Lefebvre, Superior General’s Letter, April 1980. Available at https://yrc.fsspx.uk/en/publications/letters/april-1980-superior-generals-letter-18-759

Ibid.

The Society of St Pius X, The Problem of the Liturgical Reform, Angelus Press, Kansas City, Missouri, 2001. N. 122.

Canon 2822 (1983 CIC 28): A custom beyond the law, if it has been knowingly observed by a community with the intention of obliging itself, leads to law, if the custom was equally reasonable and legitimately observed for forty continuous and complete years.

Cardinal Archbishop and Bishops of the Province of Westminster, A Vindication of the Bull “Apostolicæ Curæ”, 1898. Longmans Geen, and Co, London, Ch 24.

Ibid.

This gives rise to the difficult situation of places where there are unquestionably valid priests working with men ordained in the new rites. Here, we need to take account of a number of different factors.

For example, if a particular order occasionally works with “Novus Ordo priests” in one part of the country (or in another country), it would likely be a negative doubt to wonder about the hosts reserved in a tabernacle in another area. Without some positive reason, it seems unnecessary to engage in negative doubts about whether such “Novus Ordo priests” had been in the vicinity recently, and that one of them had replenished the hosts for the tabernacle.

It does not seem reasonable to think that, without positive reason, the average Catholic is obliged to worry about the history and lineage of a given celebrant, or whether the hosts were consecrated by a “Novus Ordo priest” who may or may not have been present in the Church in the preceding days.

John A. McHugh, O.P. and Charles J. Callan, O.P., Moral Theology: A Complete Course Based on St. Thomas Aquinas and the Best Modern Authorities, n. 2682

I don't know if this provides any clarity. This matter will be argued, ad infinitum

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wlEsReiIMyc

Hello, Mr. Wright. I hope you’re doing well. I have a question about footnote #7 as I was quite intrigued when I saw it. Where could I find the book referenced there? I did a quick Google search and nothing came up. Thank you very much.