Papal elections without the cardinals? – Cardinal Billot

It's sometimes said that if all cardinals died, defected or disappeared during a vacancy of the Holy See, there would be no way to elect a new pope. Louis Cardinal Billot give this idea the lie.

Editor’s Notes

This is a continuation of our series Papal Elections Without Cardinals? This series is presenting various opinions proposed as to how the Church could elect a new pope in the absence of the normal electors.

A ‘dead end’?

We are sometimes told that an extended vacancy of the Holy See and/or the disappearance of all cardinals results in a ‘dead end,’ as we would therefore have no way of obtaining or electing a new successor. But – we are told – as there must be perpetual successors to St Peter, an extended vacancy of the Holy See is therefore impossible.

These ideas are also sometimes used to bolster certain versions of Bishop Guérard des Lauriers’ so-called ‘cassiciacum thesis’ as a means of explaining the current situation in the Church.

Without proffering any opinion on this thesis, or on the current putative college of cardinals’ right to vote, or anything else, we can note that the ‘dead-end’ line of argument depends on dubious premises.

Pre-conciliar theologians

The impossibility of a long interregnum was by no means obvious to theologians writing prior to our time. Cardinal Billot himself writes:

“God can indeed allow the vacancy of the Holy See to be prolonged for some time. He can also permit doubt to concerning the legitimacy of the election of one or another candidate.”1

The impossibility of an election without the cardinals was also by no means obvious to such men. There have been several great theologians in history who have considered similar (even if not identical) situations to our own, without feeling obliged to either rule out an extended vacancy, nor to invent novel theses to explain one.

As implied by the idea of a series of such texts, no individual text published resolves the wider question, of how this could be achieved. The purpose of this series is merely to show that it is false to say that a long interregnum and/or the disappearance of legitimate cardinals is a dead end.

It seems wise to have as many ideas on the table as possible. It is not obvious that there can be only one single way out of our situation; nor does it seem that the various parties at the Council of Constance were agreed on what they should do (or what was happening at the time) with regards to the three claimants, or on the exact mechanism by which the later Pope Martin V was elected.

We are not declaring how the current crisis will end, or how a new Roman Pontiff be elected. In fact, we do not need to adopt a given opinion on this topic, or to present a “plan” to restore the Church. It is hardly obvious that doing so is our business.

In any case, the point is this: theologians and others have long considered how the Church might obtain a pope without any cardinals, and far from denying the possibility outright, they have presented solutions. This is sufficient to refute the objection at hand.

Even a solution which is temporarily practically unworkable – at least, for the present – refutes the claim that this is a dead end.

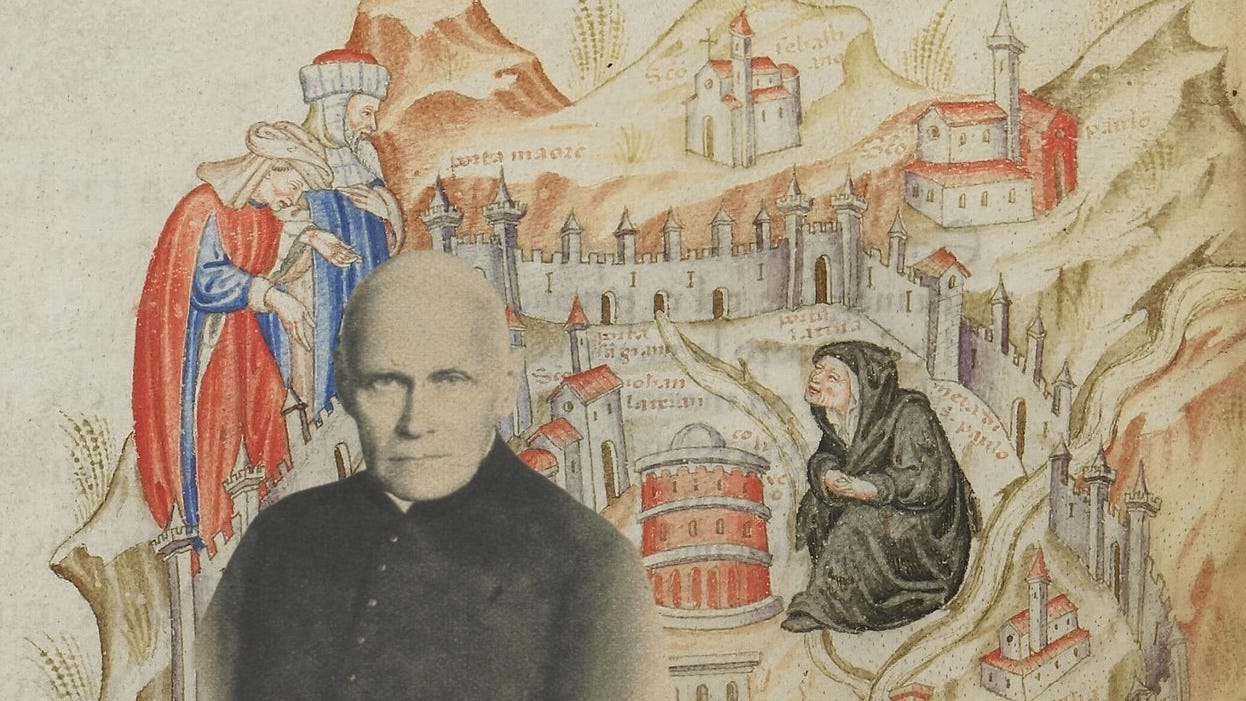

This text from Cardinal Billot

The below text is from Louis Cardinal Billot’s De Ecclesia Christi. Billot was a professor at the Gregorian University in Rome, a consultor to the Holy Office and one of the most significant theologians in recent decades. He was remembered in laudatory terms by Pius XII,2 and praised by Cardinal Merry del Val3 and Archbishop Lefebvre.4

Fr Henri le Floch – the Rector of the French Seminary in Rome whilst Archbishop Lefebvre was a seminarian – said of Cardinal Billot’s works:

‘They form a temple of sacred science, where treasures are accumulated; one might also say an “arsenal” where, for the present and for the future, the defenders of truth will find weapons in the intellectual patrimony that he has constituted and in the principle of development that he has laid down.

‘His doctrine and his method are more necessary than ever, if we wish to save minds from the deluge of errors or sterile opinions under which they are submerged.’5

It is from Cardinal Billot’s temple, treasury, and arsenal that we shall be drawing this explanation.

On the Church of Christ

Louis Cardinal Billot

Thesis XXIX §1 pp 609-612

That the legitimate election of the Pope now depends de facto solely on pontifical law is demonstrated by a simple and obvious argument, namely that the law regulating the election was enacted by the supreme pontiffs. Therefore, until it is abrogated by the Pope himself, it remains in force, and there is no authority in the Church, even during a vacancy of the Holy See, that can alter it.

‘For the Pope appoints those who are to elect, and he modifies and limits the act of election in such a way that any election conducted otherwise is invalid.

‘It is evident that neither the Church nor a council has this authority in the absence of the Pope, because the entire Church cannot authoritatively change a law made by the Pope: for example, it cannot determine that the election does not pertain to the true and certain Cardinals, or that a Pope elected by less than two-thirds of the Cardinals is valid.

‘However, conversely, the Pope could indeed determine this, because the one who authoritatively establishes a law also has the power to abolish it in matters of positive law.’6 (Cajetan)

Therefore, if, for instance, the Holy See were to become vacant during the Vatican Council, the legitimate election would not pertain to the Fathers of the Council, but solely to the usual electors, as Pius IX expressly provided by a special bull.

Thus, the only question we can ask is whether it could be possible for any authority, other than pontifical authority, to determine the conditions of an election.

In this, there is no doubt regarding the authority of an ecumenical council, which is not distinct from the pontifical power, since the decrees of ecumenical councils must be confirmed by the Pope.

Hence, the question concerns only some other inferior authority. But the conclusion must be negative, because since primacy was given to Peter alone for him and his successors, it pertains solely to him, that is, to the Supreme Pontiff alone, to determine the manner of the transmission of the power which he has received, and thus also of the election by which this transmission is effected. Furthermore, every law concerning the order of the universal Church transcends the natural limits set for any power less than supreme. But the election of the supreme pontiff undoubtedly pertains to the order of the universal Church. Therefore, by its nature, it is reserved for the determination of the one entrusted with the care of the entire community by Christ.

And these conclusions indeed hold without controversy for the regular and ordinary state of things.

Extraordinary situations

However, the question arises as to what the law would be, if an extraordinary case occurred in which it is necessary to proceed with the election of the Pope, but in whcih it is no longer possible to observe the conditions previously determined by pontifical law. This is what many believe happened during the Great Schism in the election of Martin V.

Moreover, assuming such circumstances could occur, it must be readily admitted that the power of election would devolve to a general council. For it is a principle of natural law that in such cases, the attribution of superior power devolves to the next immediate authority, precisely to the extent required to preserve the society and to escape the extremities of necessity.

‘In a case of ambiguity (because it is not known whether someone is a true Cardinal... upon the death or uncertainty of the Pope, as seemed to occur during the Great Schism initiated under Urban VI), it must be asserted that in the Church of God there is the power to the apply the papacy to a man, with the due requirements being observed.

‘And then by the way of devolution, this power seems to devolve to the universal Church, as if the electors determined by the Pope no longer exist.’7 (Cajetan)

It is not difficult to understand this solution, if one accepts the possibility of the case. But whether such a case ever actually occurred is an entirely different question. Indeed, the election of Martin V is now generally considered by scholars to have been conducted not by the authority of the Council of Constance itself, but by the faculties expressly granted by the legitimate Pope Gregory XII before he resigned the papacy [N.B.: See Note I below], so that Cardinal Franzelin rightly and deservedly says that…

‘… with humble praise, we should marvel at the providence of Christ the King, the spouse and head of the Church, who without violating any laws calmed those enormous disturbances [of the “Great Western Schism”] which were caused and sustained by the greed and ignorance of men; demonstrating very clearly that the indefectibility of the rock on which he built his Church does not rely on human strength, but on divine fidelity in his promises and omnipotence in governance, so that the gates of hell will not prevail against it.’8

And these, indeed, are concerning the election of the person of the Pope. But now the question is whether it is possible for a person duly elected and once elevated to the pontificate ever to cease to be Pope, and if so, by what means this could happen.

Note I – On the Great Western Schism

This was a long footnote in Billot’s original. For ease of reading, I am including it as a note immediately following the extract.

The legitimacy of the election of Urban VI now seems universally established; and from it follows the legitimacy of Urban's successors – that is, Boniface IX, Innocent VII, and Gregory XI. Furthermore, Gregory XII, by the fullness of his power, constituted the Council of Constance as a true and legitimate council 'for the extirpation of the horrible schisms and the complete and desirable union to be achieved.' This constitution of Gregory was solemnly promulgated by his legate Cardinal de Dominicis in Session XIV:

‘In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, amen.

‘By the authority of our lord the Pope himself, insofar as it pertains to him... that Christians dissenting under the profession of different pastors may be united in the unity of Holy Mother Church and the bond of charity, “I convoke this holy general council, and I authorize and confirm all that is to be done by it,” according to the manner and form fully contained in the letters of our lord the Pope.’

Then in Session XVI, by the authority imparted to it, the Synod decreed the manner and form of the future election of the Roman Pontiff after the vacancy of the Holy See, reserving it to the council on this occasion.

Finally, in the same Session XVI, Gregory's voluntary abdication was accepted. Through this renunciation, the Apostolic See was truly left vacant, and therefore the council, by the faculties attributed to it by the supreme pontifical power, could legitimately proceed, according to the manner, form, place, time, and matter ordained by the council itself, 'to the canonical and certain election of the one future supreme Pontiff,' and it happily completed this after two years in the person of Martin V.

Thus Franzelin – see also the documents which he cites.

Papal elections without the cardinals, and the state of the Church during a papal interregnum

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter and Telegram:

Louis Cardinal Billot, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, Tomus Prior, Prati ex Officina Libraria Giachetti, Filii et soc, 1909, Th. XXIX §. 3, p 621

In 1953, Pope Pius XII said of him in an allocution to the Gregorian University:

“Let us gladly recall our teachers such as Louis Billot, to name one, who, with spiritual distinction and intellectual acumen, incited us to venerate the sacred studies and love the dignity of the priesthood.”

Quoted in Fr Dominique Bourmaud, ‘An Anti-Liberal Theologian’, The Angelus, May 2016, available at http://www.angelusonline.org/index.php?section=articles&subsection=show_article&article_id=3845

Cardinal Merry del Val called him “the honour of the Church and of France.” Quoted ina letter to Mgr Sevin, Archbishop of Lyon in 1913. Quoted in Henri le Floch, Le Cardinal Billot – Lumière de la Théologie, 1946, p 45.

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre called “an eminent and extraordinary professor” and said that “[h]is books of theology are magnificent.” The Little Story of My Long Life, Sisters of the Society of Saint Pius X, Browerville, MN, 2002, p 30

Henri le Floch, Le Cardinal Billot – Lumière de la Théologie, 1946, p 10.

Cajetan, Tract I. de auctoritate Papae et Concilii, c. 13.

Cajetan, Ibid.

Franzelin, De Ecclesia, Thes. XIII, in the Scholion.

Now we have an impressive list of authorities who have expressly taught the Church can lose the College of Cardinals:

1. Thomas Cajetan

2. Louis Cardinal Billot

3. Caspar Hurtado

4. Francis Victoria

5. St Robert Bellarmine

6. And counting ...

This is so easy to prove: What was absent from the Church as at 100AD after the death of the last Apostle most certainly does not belong to her essence, and as such can be lost at anytime.

Put in other words, what was not ALWAYS present in the Church since her institution does not belong to her essence.

1. College of Cardinals

2 Actual occupation of ecclesiastical sees, including the Apostolic See

3. Actual presence of the Church in all countries

4. Etc

Let's now escape the tunnel vision we've been under for decades with fallacious arguments!!!

It'll be good to see if there's ANY author who considered the question and did not provide the same solution (what is now essentially unanimous), differing only in details irrelevant to our day.