One psychological challenge of fasting today—and ways to beat it

So you've decided to fast for more than just Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. But there's a serious barrier confronting us in fulfilling this precept of the natural law.

So you've decided to fast for more than just Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. But there's a serious barrier confronting us in fulfilling this precept of the natural law.

Did Paul VI destroy the Church’s penitential regime?

The received traditionalist narrative is that Paul VI basically destroyed the laws of fasting and abstinence with his 1966 apostolic constitution Paenitemini, reducing the days of obligatory fast to Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, and days of abstinence to these days and Fridays throughout the year. However, the picture seems to be more complicated than this.

Previously, we have seen that…

Fasting is a precept of the natural law, and is not simply interchangeable with other practices of mortification

It essential for restoring the right order within ourselves, and for strengthening us against sin

It is also essential, according to the saints, for spiritual growth and for the healing of the modern world

That the Church has had good reasons for mitigating the severity of her fasting regime over the centuries

What this fasting regime for Lent (and the year) was prior to the Second World War, as explained by Fr Henry Davis SJ.

Having seen all this, one might decide that it is necessary to fast more in Lent than merely on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday—albeit keeping in mind the dangers of pride.

Indeed, Lent is all about fasting. This is not to diminish the importance of prayer and almsgiving in Lent, but it is to recognise that the Church (and her liturgy) give a primacy to fasting as the mortification of the season; they do not treat it as interchangeable with alternative mortifications, be they hair-shirts, cold showers, giving up sweets, or anything else.

The first logical solution, on deciding to fast in Lent, might be returning to the laws in force prior to Vatican II.

But here we meet a problem. Even before Paul VI’s changes, the Church’s penitential regime had been temporarily mitigated due to the Second World War, and these mitigations do not seem to have been rescinded before Paul VI’s changes.

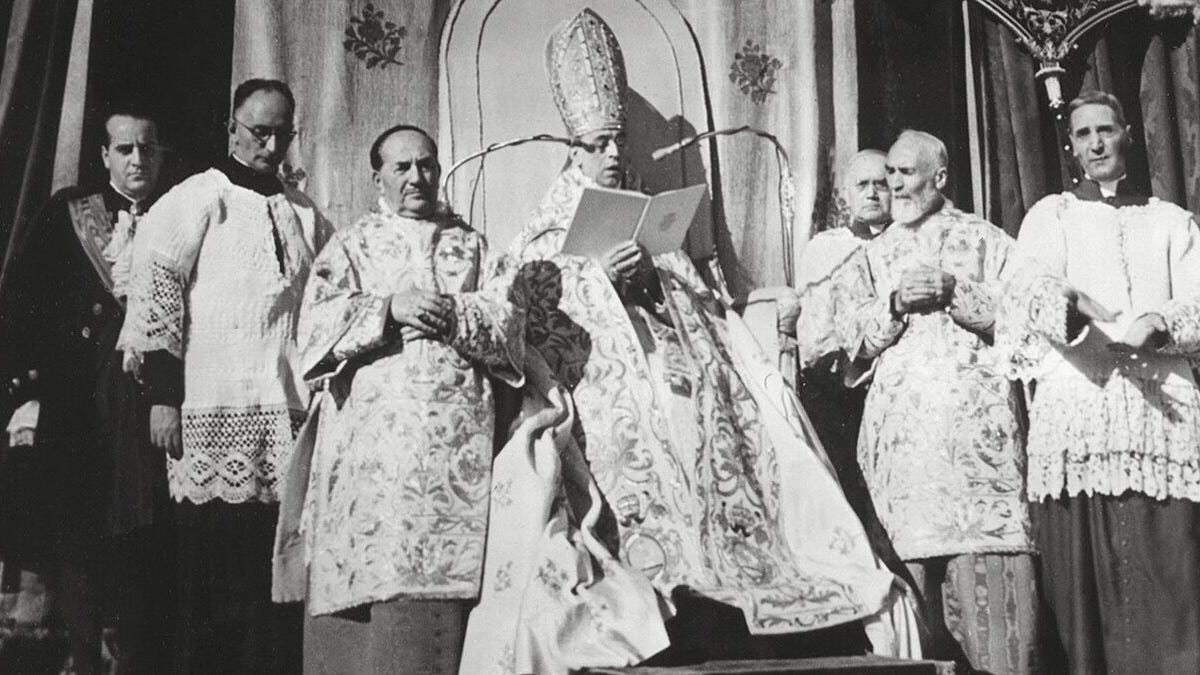

What happened under Pope Pius XII

In 1941, Pius XII granted an indult which gave ordinaries the power to reduce the obligations of fast and abstinence to just Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.1 In 1949, the Holy See “partially restored” the penitential regime, by re-establishing more days of abstinence, and insisting on two further fast days (the vigils of the Assumption and Christmas).2 Nonetheless, the 1949 decree left intact the power of dispensation given to ordinaries.

This power was used to different degrees in different places, but at least by 1963, the English bishops had “availed themselves of the mitigation.”3 Similar mitigations took place in 1949 in the United States. It is not clear when or whether these local mitigations were rescinded, and in which dioceses.

In 1958, Pius XII died and the Catholic Church entered a grave crisis—apparently leaving the 1949 decree in force long after it may have been intended. As we have already seen, the putative authorities had no interest in restoring a penitential regime that conformed to the requirements of the natural law.

This has left Catholics in the conundrum of working out what is and is not obligatory, whether in itself, or by virtue of the positive law that was in force prior to the Council.

Before we consider the practical implications of this difficulty—and ways to address it—we must make two brief observations.

The rest is a “thank you” article for our annual/monthly subscribers. If you like The WM Review, please consider joining this elite list of legends!