Sacrifice and triumph – How does Christ’s passion reconcile us to God?

“The atonement is the work of love.”

Christ’s passion is the great triumph of his incarnation. Dom Columba Marmion writes:

“It is the hour wherein Jesus consummates the sacrifice that is to give infinite glory to His Father, to redeem humanity, and reopen to mankind the fountains of everlasting life.”[1]

The passion is the manifestation of God’s glory and of the glorification of the God-Man himself. It is the single, infinitely pleasing and worthy sacrifice, which was offered to God on behalf of a race otherwise unable to do so.

No doubt, the idea that Christ triumphs and is glorified in the humiliations of his passion is a mystery. Let us reverently try to understand it, insofar as we are able.

As Amazon Associates, we earn from qualifying purchases through our Amazon links. Click here for The WM Review Reading List (with direct links for US and UK readers).

Sin

At some point, nearly every Christian asks himself why Christ needed to suffer to save us.

The answer to this – which also explains the reason for an eternal Hell – is often given in terms expressed by St Thomas Aquinas:

“[A] sin which is committed against God, is infinite: because the gravity of a sin increases according to the greatness of the person sinned against (thus it is a more grievous sin to strike the sovereign than a private individual), and God’s greatness is infinite. Therefore an infinite punishment is due for a sin committed against God.”[2]

Elsewhere St Thomas writes what we all know as well: “no penalty endured could man pay [God] enough satisfaction” for the debt of sin.[3] The Catholic Encyclopaedia explains further, referring to the theology of St Anselm:

“No sin, as [St Anselm] views the matter, can be forgiven without satisfaction. A debt to Divine justice has been incurred; and that debt must needs be paid. But man could not make this satisfaction for himself; the debt is something far greater than he can pay; and, moreover, all the service that he can offer to God is already due on other titles.

“The suggestion that some innocent man, or angel, might possibly pay the debt incurred by sinners is rejected, on the ground that in any case this would put the sinner under obligation to his deliverer, and he would thus become the servant of a mere creature.

“The only way in which the satisfaction could be made, and men could be set free from sin, was by the coming of a Redeemer who is both God and man. His death makes full satisfaction to the Divine Justice, for it is something greater than all the sins of all mankind.”[4]

This was the central dilemma, to which the incarnation of Christ provided the answer.

Sacrifice and God’s wrath

St Thomas explains that a sacrifice “is something done for that honor which is properly due to God, in order to appease Him.”[5] He also explains:

“He properly atones for an offense who offers something which the offended one loves equally, or even more than he detested the offense.”[6]

By assuming human nature, Christ was able to offer a sacrifice to God as one of us, as man. This sacrifice was of infinite value, “inasmuch as it was God’s flesh” that suffered, and inasmuch as he endured this extreme suffering out of perfect obedience and exceeding love for God.[7]

In so doing, justice was perfectly fulfilled, because our otherwise unpayable debt was paid in full; and yet also in so doing, God manifested his great love and mercy for our fallen race.

We know that God the Father delivered his Son to this passion specifically out of love for us, so that we might not perish but have everlasting life (John 3.16). But many are tempted to think that there is something unjust about God’s justice. Many people today are troubled by the idea of an angry God demanding the blood of his Son before being willing to forgive us. How, they ask, how could a good God demand the sufferings of the passion in order to be appeased?

First, guilty as we are, we should note that we are not in a position to be judging the justice or goodness of God, the consequences of sin, or the propriety of his wrath.

However, we should not see this matter as God the Father demanding something in a wicked or tyrannical way. The Catholic Encyclopaedia article on the atonement comments on certain unhelpful ways of thinking about the matter:

“It is true of course that sin incurs the anger of the Just Judge, and that this is averted when the debt due to Divine Justice is paid by satisfaction. But it must not be thought that God is only moved to mercy and reconciled to us as a result of this satisfaction.

“This false conception of the Reconciliation is expressly rejected by St. Augustine (In Joannem, Tract. cx, section 6). God’s merciful love is the cause, not the result of that satisfaction.

“[A] second mistake is the tendency to treat the Passion of Christ as being literally a case of vicarious punishment. This is at best a distorted view of the truth that His Atoning Sacrifice took the place of our punishment, and that He took upon Himself the sufferings and death that were due to our sins.”[8]

Substitution

Regarding this “second mistake”, John Salza presents the following comparison:

“If I steal money from a stranger, the stranger will seek a legal remedy. He will not care how much I apologize or try to appease him in other ways. He will only want his money back. That is because I don’t have a personal relationship with the stranger.

“However, if I steal from my parents, they won’t care as much about the money. They will be personally offended. Even if I return the money to them, they will continue to be hurt by my actions. It will not be about the money, but about my having harmed our relationship.

“Whereas the stranger will desire legal payment, my parents will desire to be appeased. They will desire some sort of sacrifice from me to prove my love for them, and to restore their honor and justice. A heart-felt apology in charity will mean far more to them than a return of the money. In a word, they will want to be propitiated for my sin.”[9]

However, Salza continues:

“[A]lthough Scripture uses propitiation to describe Christ’s atoning work, it never uses substitution. […]

“If my sister pays my parents the money I stole from them, her offer is one of substitution but not propitiation. Her payment will substitute for the money I owe my parents and they will be legally made whole. But they will not be propitiated.

“In fact, my parents may be even angrier at me. If my sister pays off the stranger, however, he will likely be satisfied with the substitute payment. He will be happy as long as he gets his money back (with maybe some interest). Propitiation is part of personal, intimate relationships (such as between parents and children); substitution is not.”[10]

This image is instructive. An opposition between propitiation and substitution may be pressed too far, as the text below shows, and as the innocent Christ really did suffer and offer the sacrifice for the guilty.

However, it is necessary to understand this suffering on behalf of another in the right way. To this end, Salza’s image does demonstrate the difference between understandings of the passion – as well as one aspect of why there is no salvation outside the Church. It is Christ who has offered the sacrifice, and we must be incorporated into him by faith and charity if we wish to benefit from the salvation which he has merited. As St Thomas explains:

“[G]race was bestowed upon Christ, not only as an individual, but inasmuch as He is the Head of the Church, so that it might overflow into His members; and therefore Christ’s works are referred to Himself and to His members in the same way as the works of any other man in a state of grace are referred to himself. […]

“The head and members are as one mystic person; and therefore Christ’s satisfaction belongs to all the faithful as being His members. Also, in so far as any two men are one in charity, the one can atone for the other.”[11]

Christ’s love

Returning to the question of “God’s cruelty”, St Thomas writes:

“It is indeed a wicked and cruel act to hand over an innocent man to torment and to death against his will.

“Yet God the Father did not so deliver up Christ, but inspired Him with the will to suffer for us. […]

“Christ as God delivered Himself up to death by the same will and action as that by which the Father delivered Him up; but as man He gave Himself up by a will inspired of the Father.

“Consequently there is no contrariety in the Father delivering Him up and in Christ delivering Himself up.”[12]

Further, we should remember that Christ himself “loved the Church,” and recall the words of St Paul to the Ephesians:

“Christ also loved the church and delivered himself up for it: That he might sanctify it, cleansing it by the laver of water in the word of life: That he might present it to himself, a glorious church, not having spot or wrinkle or any such thing; but that it should be holy and without blemish.” (Eph. 5.25-7)

As Dom Columba Marmion says of this text and this question:

“[I]t is, before all, love for His Father that urges Christ to accept the sufferings of the Passion. But the love that He bears towards us likewise urges Him.

“At the Last Supper, when the hour for achieving His oblation draws near, what does He say to His apostles gathered around Him? ‘Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’

“And this love which surpasses all love, Jesus is about to show forth to us, for, says St. Paul, ‘Christ dies for all.’ He died for us when we were His enemies. What greater mark of love could He give us? None.”[13]

It would be completely wrong to see Christ as a mere passive victim of circumstances. He himself, as St Ignatius says, “wants to suffer.”[14]

Pope Pius XII mentions, in Mystici Corporis Christi, that from the first moment of Christ’s incarnation, “all the members of His Mystical Body were continually and unceasingly present to Him, and He embraced them with His redeeming love.”[15] If this was so in Our Lady’s womb, then it certainly must have been so for the passion.

In other words, Christ really wants to offer the sacrifice: first for the sake of God’s justice and glory; and next because he wants us – whom he knew and loved, even then – to benefit from this sacrifice.

Finally, far from seeing the passion as manifesting a lack of love on the part of God the Father, Fr Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange writes:

“God the Father, in asking His Son to die for us as a victim, has loved Him with a supremely great love, since He has wished thereby to make Him the victor over sin, the devil, and death.”[16]

To summarise, in his passion, Christ obediently atoned for our sins by offering himself as a sacrifice, whose infinite value exceeded the evil of sin, and pleased God more than sin offended his infinite majesty.

In suffering his passion, Christ redeemed us from servitude to sin and to the devil.[17] Insofar as he is the Head of the Church, this sacrifice also merited grace and salvation for those who are incorporated into him as the members of his mystical body – and thus reconciled us to God.[18] Because of all this, we can see why the Catholic Encyclopaedia concludes:

“[T]he Atonement is the work of love. It is essentially a sacrifice, the one supreme sacrifice of which the rest were but types and figures. And, as St. Augustine teaches us, the outward rite of Sacrifice is the sacrament, or sacred sign, of the invisible sacrifice of the heart.

“It was by this inward sacrifice of obedience unto death, by this perfect love with which He laid down his life for His friends, that Christ paid the debt to justice, and taught us by His example, and drew all things to Himself; it was by this that He wrought our Atonement and Reconciliation with God, ‘making peace through the blood of His Cross’.”[19]

Conclusion

No man in history but Christ could have offered this sacrifice. When we consider his burning zeal for God’s glory, and his tender love for our race estranged from God, we can start to understand why Christ was so “straitened” for the hour of his passion. In the words he spoke to Pilate:

“For this was I born, and for this came I into the world.” (John 18.37)

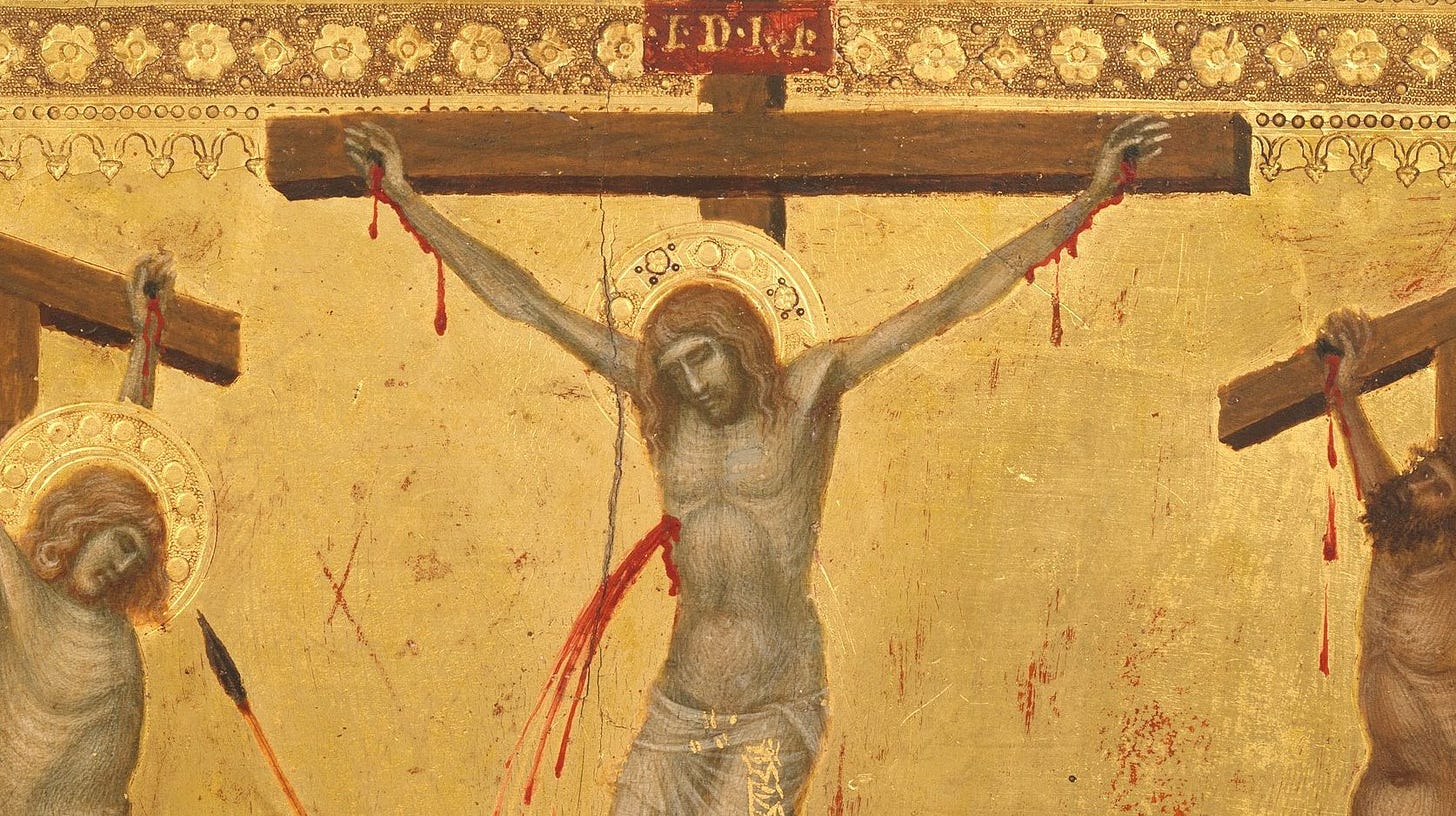

This also shows us why it is fitting that his glorified body retains the scars of the crucifixion. St Thomas tells us that Christ wears these five holy wounds “as an everlasting trophy of His victory.”[20] Trophies are given to the victors – and thus we can see that the humiliations and sufferings of his passion, far from being a defeat, mark the triumph of Christ. He is the great high priest who offers the supremely pleasing sacrifice, and the redeemer who reconciles fallen man to God.

The Church’s liturgy commemorates the sufferings and sorrows of Christ, most notably in the Mass of Palm Sunday and in the offices of Tenebrae. But in the liturgy of Good Friday – the centre of the Sacred Triduum and the most direct meditation on the Passion – it seems like we are not confronted with the Man of Sorrows at all.

On the contrary, the liturgy presents us with the Christ who “reigns from the tree” – as depicted by Mgr Robert Hugh Benson in Dawn of All:

“… for an instant it seemed as if he saw in mental vision that which they described—a Supreme Dominant Figure, wounded indeed, yet overmastering and compelling in His strength—no longer the Christ of gentleness and meekness, but a Christ who had taken His power at last and reigned, a Lamb that was a Lion, a Servant that was Lord of all; One that pleaded no longer, but commanded…”[21]

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone. If you have benefitted from our content please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material!

Thank you!

[1] Dom Columba Marmion, Christ in His Mysteries, p 248. Trans. Mother M. St. Thomas, Sands & Co., London, 9th Edition, 1939.

[2] St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (henceforth ST), Ia IIae, Q87 A4 Obj. 2. Trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Second and Revised Edition, 1920. Text taken from New Advent.

While this text is found in an objection to the thesis of the given question, St Thomas accepts the terms as being relevant to one aspect of sin, namely the turning away from the infinite good, which is God. This is made explicit in the response, which itself refers back to the body of the answer:

“Punishment is proportionate to sin. Now sin comprises two things. First, there is the turning away from the immutable good, which is infinite, wherefore, in this respect, sin is infinite. Secondly, there is the inordinate turning to mutable good. In this respect sin is finite, both because the mutable good itself is finite, and because the movement of turning towards it is finite, since the acts of a creature cannot be infinite.”

[3] ST III Q47 A3

[4] William Kent. “Doctrine of the Atonement.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 4 Apr. 2023, available at http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02055a.htm

[5] ST III Q48 A3

[6] ST III Q48 A2

[7] ST III Q48 A2

[8] Kent

[9] John Salza, The Mystery of Predestination, ebook version, chapter 4. Tan Books, Charlotte, North Carolina, 2010.

[10] Ibid.

[11] ST III Q48 A1-2

[12] ST III Q47 A2

[13] Dom Columba Marmion, 251.

[14] St Ignatius, Spiritual Exercises, p 98. Trans. Louis J. Puhl SJ, The Newman Press, Worthington, Ohio, 1951.

[15] Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Mystici Corporis Christ, 1943, n. 75. Available at: https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_29061943_mystici-corporis-christi.html

[16] Fr Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange, Our Savior and his Love for Us, p 203. B. Herder Book Co., London, 1951.

[17] “[B]y withdrawing from God’s service, he, by God’s just permission, fell under the devil’s servitude on account of the offense perpetrated. But as to the penalty, man was chiefly bound to God as his sovereign judge, and to the devil as his torturer.” ST III Q48 A4

[18] ST III Q48 A1.

[19] Kent

[20] ST III Q54 A4

[21] Mgr. Robert Hugh Benson, Dawn of All, p 245. B. Herder, St Louis, MO, 1911.