St Thérèse of Lisieux’s ‘Little Way’ – Dom Eugene Boylan explains

Sometimes presented as childish and sentimental, 'The Little Way' of St Thérèse of Lisieux ('The Little Flower') is profound, hard – and it is for all of us today.

Editors’ Notes

The following is an extract from Dom Eugene Boylan’s modern classic, This Tremendous Lover, explaining ‘the little way’ of St Thérèse of Lisieux and its importance to our day.

The following section summarises the text:

‘Everyone should study her doctrine, but let us add a word of warning; one must not let the childlike language and manner of the saint hide the fact that she was a woman in whom grace had forged and tempered a will of steel, a woman whose very childlike charm hid sufferings that are beyond all telling.

‘And, if one may judge by the extraordinary honours the Church has showered on her in a few short years, she became one of the greatest saints the Church has known, by a life in which there was nothing extraordinary, in the usual sense of the word.

‘Yet her way is recommended to all by the highest spiritual authority upon earth.’

Union with Christ Through Humility

From

This Tremendous Lover

Dom Eugene Boylan

Published here in gratitude to St Thérèse of Lisieux

‘Thou shall love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart and thy whole soul, with all thy mind and all thy strength.’

Thomas à Kempis puts these words on our Lord’s lips:

What more do I ask of thee than to try to give thyself up entirely to Me? Whatever thou givest besides thyself is nothing to Me: I seek not thy gift but thyself! Just as thou couldst not be content without Me, though thou possessest everything else; so nothing thou offerest can please Me unless thou offerest Me thyself! […]

Behold, I offered My whole self to the Father for thee, and have given my whole Body and Blood for thy food: that I might be all thine, and thou mightest be all and always Mine. But if thou wilt stand upon thy own strength, and wilt not offer thyself freely to My will, thy offering is not perfect, nor will there be an entire union between us.1

Our humility and obedience are but the exercise of our love and desire for Jesus; they are but means of giving ourself completely to Him, as He does to us in the Mass, and that is what, by our Communion and assistance at Mass, we signify our readiness to do.

For that is the whole spiritual life—a love union with Jesus, in which each of the lovers, the divine and the human, give themselves completely to one another. It is not so much a question of acquisition of virtue, of performing heroic deeds, of amassing merit, of bearing fruit in the Church; these things are excellent, especially insofar as they come from love. But nothing less than our very self in its entirety will satisfy the Heart of Jesus, and all He asks is that we give Him our whole self in all poverty and nothingness. The great way to do that is the way shown by Jesus and by Mary—by love through humility and abandonment.

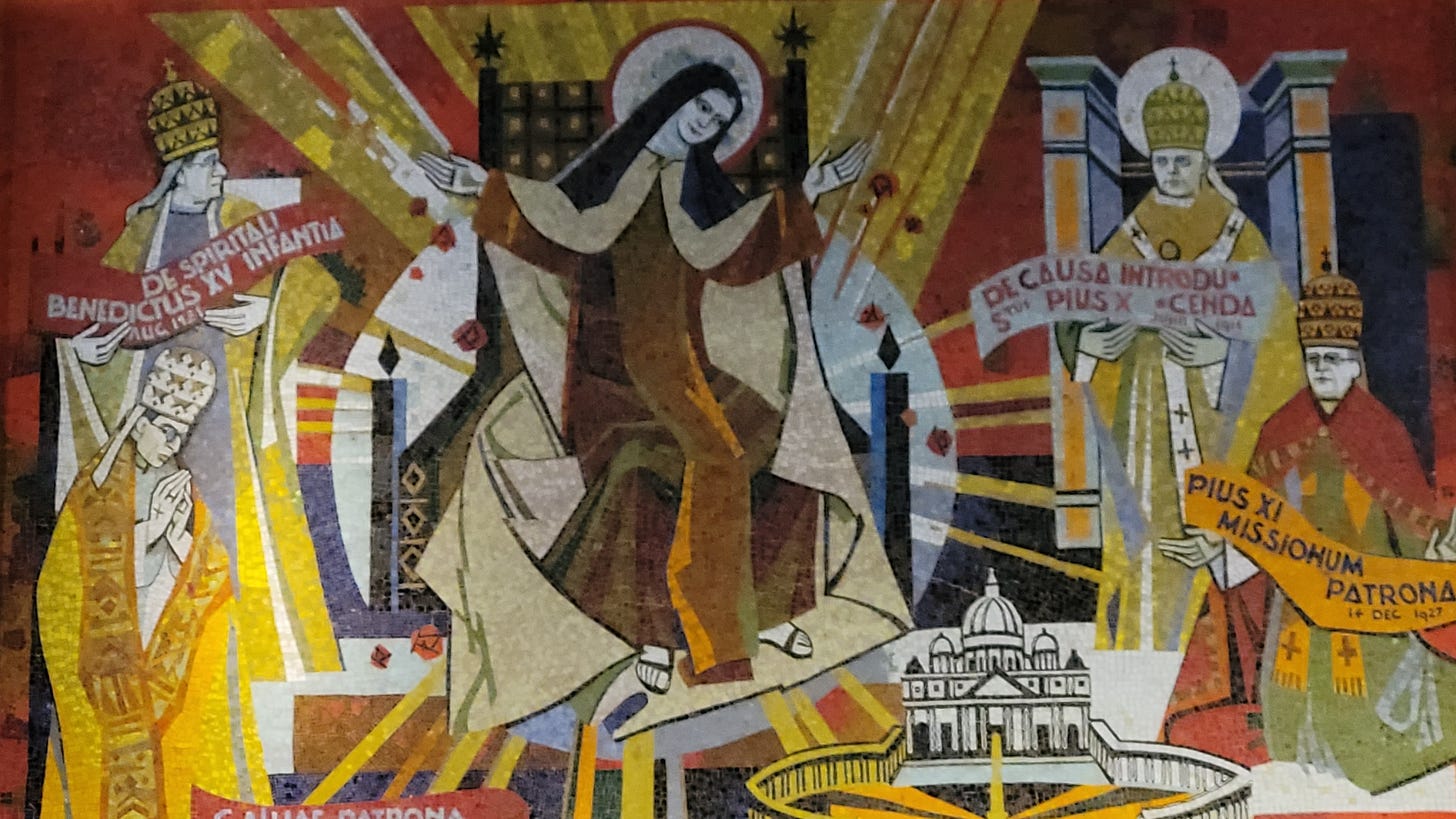

St Thérèse of Lisieux and the Popes

This way has again been brought to men’s notice in our own times by the life of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. There can be no doubt that she was raised up by God to show us the true way to holiness. One would hesitate about citing the life of an enclosed contemplative as a model for the laity, were it not for the insistence with which more than one pope has stressed the universality of her message of what is called ‘spiritual childhood.’

Her life really marks a true renaissance in the history of spirituality. Its importance cannot be exaggerated. Let us quote Pope Benedict XV in his discourse regarding the heroicity of her virtues. ‘There,’ he exclaims, referring to spiritual childhood, ‘lies the secret of holiness… for the faithful throughout the entire world…’ and he proceeds to give a complete description of this spirituality from which we quote brief passages.2

Taking as an example the confidence of a child in its mother’s protection and its certainty that she will treat it in the way best suited to its needs, the Holy Father proceeds:

So likewise, is spiritual childhood fostered by confidence in God and trustful abandonment into His hands… Spiritual childhood excludes first the sentiment of pride in oneself, the presumption of expecting to attain by human means a supernatural end, and the deceptive fancy of being self-sufficient in the hour of danger and temptation.

On the other hand, it supposes a lively faith in the existence of God, a practical acknowledgment of His power and mercy, confident recourse to Him who grants the grace to avoid all evil and obtain all good. Thus, the qualities of this spiritual childhood are admirable... and we understand why our Saviour Jesus Christ has laid it down as a necessary condition for gaining eternal life. One day the Saviour took a little child from the crowd, and showing him to His disciples, He said:

‘Amen I say to you; unless you be converted and become as little children you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.’ (Matt. 18.3)

‘Who, thinkest thou, is the greater in the kingdom of heaven? […] Whosoever shall humble himself as this little child, he is the greater in the kingdom of heaven.’

And again on another day, Jesus said: ‘Suffer little children to come to me, and forbid them not; the kingdom of heaven is for such. Amen I say to you, whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a child shall not enter into it.’ (Mark 10.14-15)

The Holy Father continues:

It is important to notice the force of these divine words, for the Son of God did not deem it sufficient to affirm positively that the kingdom of heaven is for children—Talium est enim regnum coelorum—or that he who will become as a little child shall be greater in heaven, but He explicitly threatens exclusion from heaven for those who will not become like unto children… We must conclude then that the Divine Master was particularly anxious that His disciples should see in spiritual childhood the necessary condition for obtaining life eternal.

Considering the insistence and the force of this teaching, it would seem impossible to find a soul who would still neglect to follow the way of confidence and abandonment, all the more so, we repeat, since the divine words, not only in a general manner, but in express terms, declare the mode of life obligatory, even for those who have lost their first innocence.

Some prefer to believe that the way of confidence and abandonment is reserved solely for ingenuous souls whom evil has not deprived of the grace of childhood. They do not conceive the possibility of spiritual childhood for those who have lost their first innocence.

And the Holy Father proceeds to show that our Lord’s use of the words ‘be converted’ and ‘become’ indicate that a change is to be made, and that therefore the words apply particularly to those who are no longer innocent. He continues:

Any such thought as that of reassigning the appearance and helplessness of early years would be ridiculous; but it is not contrary to reason to find in the words of the Gospel the precept addressed alike to men of advanced years to return to the practice of spiritual childhood.

During the course of centuries, this teaching was to find increased support in the example of those who arrived at heroic Christian perfection precisely by the exercise of these virtues. Holy Church has ever extolled these examples in order to make the Master’s command better understood and more universally followed.

Today, again, she has no other end in view when she proclaims as heroic the virtues of Soeur Therese de L’Enfant Jesus.3

May we add the words of Pius XI at her canonisation:

We today conceive the hope of seeing spring up in the souls of Christ’s faithful a holy eagerness to acquire this evangelical childhood, which consists in feeling and acting under the empire of virtue as a child feels and acts in the natural order…

If this way of spiritual childhood became general, who does not see how easily that reform of human society would take place which We set before us in the early days of our pontificate?

Some good books on St Thérèse

Many books have been written to broadcast St. Thérèse’s message. No adequate summary of it can be given here. The reader is referred to:

Her own autobiography [‘Story of a Soul’]

Msgr. Laveille’s biography of the saint

Fr. Petitot’s book, St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

Since, however, we believe that this is the way of sanctification for most of the laity, we shall quote some passages from Mgr. Laveille’s work, in the hope of inducing the reader to seek further information from the mass of literature already available on the subject.4

God (Laveille writes) is a Father, and the burning ardour of His love surpasses all human tenderness.”

He Himself assures that His love is far beyond that of any mother.5

… It follows that the surest means of gaining His Heart is to remain or become again a little child in His eyes, that is to say, to recognize our nothingness in His sight, to lay our poverty before Him, to make ourselves truly little in the presence of His Majesty, confiding without fear in His sovereign goodness so that we may move Him to generosity towards us…

This secret appears simple; it contains nothing which can inspire fear in the feeblest Christian heart. It is essential, however, to discern clearly the true signification of the actions enjoined by this method. First, there is the recognition of our incapacity and poverty. But this can be recognised, and at the same time hated, reviled.

What is necessary is that we willingly proclaim our nothingness in regard to the greatness of the Almighty. In other words, the surest disposition to draw from the Father in heaven a kindly smile is humility of heart by which we really and truly love to see ourselves as we are and look with joy into the depths of our lowliness.

‘Littleness’

St. Thérèse explains:

To be little means not attributing to self the virtues that one practices, believing oneself capable of anything; it means recognizing that the good God places this treasure of virtue in the hand of His little child to be used by him when he has need of it; but always it is God’s treasure.

In fine, it means not being discouraged about our faults, for children fall often, but are too small to do themselves much harm.

Laveille continues:

This disposition is, alas, comparatively rare, even among Christians. The greater number are, indeed, willing to admit their weakness, but only to a certain point. They credit themselves with real personal strength, on which they are content to rely while all goes well, only to fall into discouragement at the first serious obstacle they meet with.

They have not understood that the child’s strength lies in its very weakness, since God is inclined to help His creatures in proportion to their recognition and humble avowal of their natural helplessness…

A second characteristic trait of spiritual childhood is poverty. The child possesses nothing of its own; everything belongs to its parents. But is it not precisely this absolute want of all things which moves the father to provide for every necessity, especially if the child is insistent in drawing attention to its excess of misery?

When this state of penury has ceased through the child’s growing up and commencing to earn his own livelihood, the father, be he ever so affectionate, discontinues his bounty.

‘Spiritual Childhood’

For this reason St. Thérèse never wished to grow up spiritually, ‘feeling incapable of gaining for myself life eternal, for I have never been able to do anything for myself alone.’

In the same way, the soul will gain everything by possessing nothing and looking to God for all. She must, however, accustom herself to await the coming of each day for the gifts thereof, asking nothing except what is needed at the present instant, because the grace required is, in God’s designs, an actual grace, to be given at the opportune moment…

The poor in spirit, when once in possession of God’s gifts, be they spiritual or corporal, will guard against any proprietorship over them, for they belong always to God, who has simply lent them and is free to take them back as He wills…

Finally, one who chooses the ‘little way’ must be resigned to remaining poor all his life. By this he will imitate the dear saint, who, while multiplying her acts of virtue, did not concern herself with storing up merits for eternity, but laboured for Jesus alone, giving over to Him all her good works to purchase souls.

St. Thérèse’s own words are full of consolation:

[T]o love Jesus, to be the victim of His love, the more weak and miserable we are, the better disposed are we for the operations of His consuming and transforming love… The sole desire of being a victim suffices; we must, however, be always willing to remain poor and weak. Herein lies the difficulty!

… Let us love our littleness, let us love to feel nothing. Then shall we be poor in spirit, and Jesus will come to seek us, be we ever so far away. He will transform us into flames of love.6

Confidence in God

[Laveille continues:]

Besides humility of heart and the spirit of poverty, something more is required. Confidence, unbounded, unwavering confidence in the merciful goodness of the heavenly Father is the infallible means of inclining His Divine Heart to compassion and bounty.

With St. John of the Cross, St. Thérèse repeated from her heart: ‘From the good God we obtain all that we hope for.’

‘The chief practical conclusions from this doctrine is that a soul initiated into this “little way” must confide in the divine mercy regarding past faults, however grave and multiplied they may have been, and that he must look to the same mercy for the pardon of his daily faults… This confidence is necessary in failure; the futility of human actions draws pity from the Divine Heart. It is equally required in darkness and aridity…’

In fine, St. Thérèse wished that no bounds should be set to our hopes and desires of attaining to holiness, supporting her words by reference to the merciful omnipotence of…

… Him who being power and holiness itself would have but to take a soul in His arms and raise it up to Him in order to clothe it with His infinite merits and make it holy.7

And asserting more definitely the efficacy of confidence even in arriving at the highest perfection, she does not hesitate to add:

If weak and imperfect souls like mine felt what I feel, not one of them would despair of reaching the summit of the mountain of love.

This way of humility, of self-forgetfulness, of reliance on God’s own holiness, is the royal road to sanctity—for everybody. The spiritual life is not so much a work of acquiring virtue and merits, as of getting rid of oneself; in fact, it is not so much a getting rid of oneself as a putting on of Christ. No more excellent commentary on St. Paul’s doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ which we outlined in the earlier chapters can be found than the life and teaching of St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

Everyone should study her doctrine, but let us add a word of warning; one must not let the childlike language and manner of the saint hide the fact that she was a woman in whom grace had forged and tempered a will of steel, a woman whose very childlike charm hid sufferings that are beyond all telling. And, if one may judge by the extraordinary honours the Church has showered on her in a few short years, she became one of the greatest saints the Church has known, by a life in which there was nothing extraordinary, in the usual sense of the word. Yet her way is recommended to all by the highest spiritual authority upon earth.

Humility and Sanctity

Humility, we repeat, is the royal road to sanctity; but it must be joined to unbounded confidence. We only forget ourselves to remember Christ, of whom we are members, and who loved us and delivered Himself to death for us. Humility is the great way of repairing the fall and failures of the past. There is no shortcoming for which it cannot more than compensate. To which effect we quote the words of a Cistercian Abbot, Blessed Guerric, a disciple of St. Bernard, with a modern Cistercian’s introduction to them:

Humility has a very special property of its own; it not only ensures that the other virtues are really virtues, but, if any one of them is wanting, or is imperfect, humility, using that very deficiency, of itself repairs the deficiency.

Therefore, if something seems to be lacking in any soul, it is lacking for no other reason than that the soul should be all the more perfect by its absence, for virtue is made perfect in infirmity. Paul, saith the Lord, my grace is sufficient for thee (II Cor. Xii, 9).

He for whom the grace of God is sufficient, can be lacking in some particular grace, not only without serious loss, but even with no small gain, for that very defect and infirmity perfects virtue; and the very diminution of a certain grace only makes the greatest of all God’s graces—namely, humility—present in a fuller measure and more stable way.

Far, then, O Lord, from thy servants let that grace be—whatever it may be—which can take away or lessen our grace in thy eyes (gratiam tui), by which, namely, although more pleasing in our own eyes, we become more hateful in Thine.

That is not grace, but wrath, for it is only fully fit to be given to those with whom Thou art angry; in whose regard Thou hast disposed such things, and that because of their simulation, thrusting them down at the very moment of their elevation and rightly crushing them even while they are raised on high.

In order, therefore, that that grace alone, without which no one is loved by Thee, should remain safe in our possession, let Thy grace and favour either take away all other grace from us, or else give us the grace of using all properly; so that having the grace by which we serve Thee pleasingly with fear and reverence, we may earn the favour of the giver through the grace of the gift, and that growing in grace, we may be truly more pleasing to Thee.8

To sum up a long chapter let us repeat again with St. Paul, ‘Gladly will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me,’ (II Cor. xii, 9) and let us be convinced that no matter what we have lost, what we have mined, or how far we have wandered into the wilderness from the right path, God can give us back all we have lost or damaged. God can show us a road—or, if necessary, build a new road for us—that leads from our present position, whatever it may be, to the heights of sanctity; humility is the Philosopher’s Stone which changes all our losses into the gold of God’s favour. He can do all for us, and He will do all if we cooperate with this grace.

What then does He ask of us? Nothing but blind faith, confident hope, ardent love, cheerful humility, and loving abandonment into the arms of our tremendous lover!

Further Reading

On St Thérèse of Lisieux:

St Thérèse of Lisieux – Story of a Soul

Mgr Laveille – The Life of St Thérèse of Lisieux

Fr Petitot’s – St. Thérèse of Lisieux – A Spiritual Renascence

Boylan’s works:

Difficulties in Mental Prayer

This Tremendous Lover

The Mystical Body and the Spiritual Life

The Spiritual Life of the Priest

The Priest’s Way to God

Morrissey – Dom Eugene Boylan: Trappist Monk and Writer

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our work. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Imitation of Christ, iv, 8.

Cf. Discourse of Pope Benedict XV, Aug. 14, 1921.

Cf. Laveille, St. Teresa of Lisieux, Cap. XII.

Laveille, St. Teresa of Lisieux, chap. XII, pp. 305, et seq.

Cf. Isaias 43.25.

Sixth Letter to S.M. du Sacré Coeur

Story of a Soul, Chap. XI

Cf. De Beato Guerrico, by P. Deodatus de Wilde, O.C.R.