St Thérèse of Lisieux's 'Little Way'—nature, advantages and necessity

The 'Little Way' of St Thérèse of Lisieux is one of the most popular ideas in modern spirituality—but what should it drive us towards in practice?

“Any such thought as that of reassuming the appearance and helplessness of early years would be ridiculous; but it is not contrary to reason to find in the words of the Gospel the precept addressed alike to men of advanced years to return to the practice of spiritual childhood.”

Pope Benedict XV in his decree on St Thérèse’s heroic virtue

Idea, Advantages and Necessity of The “Little Way of Spiritual Childhood

From

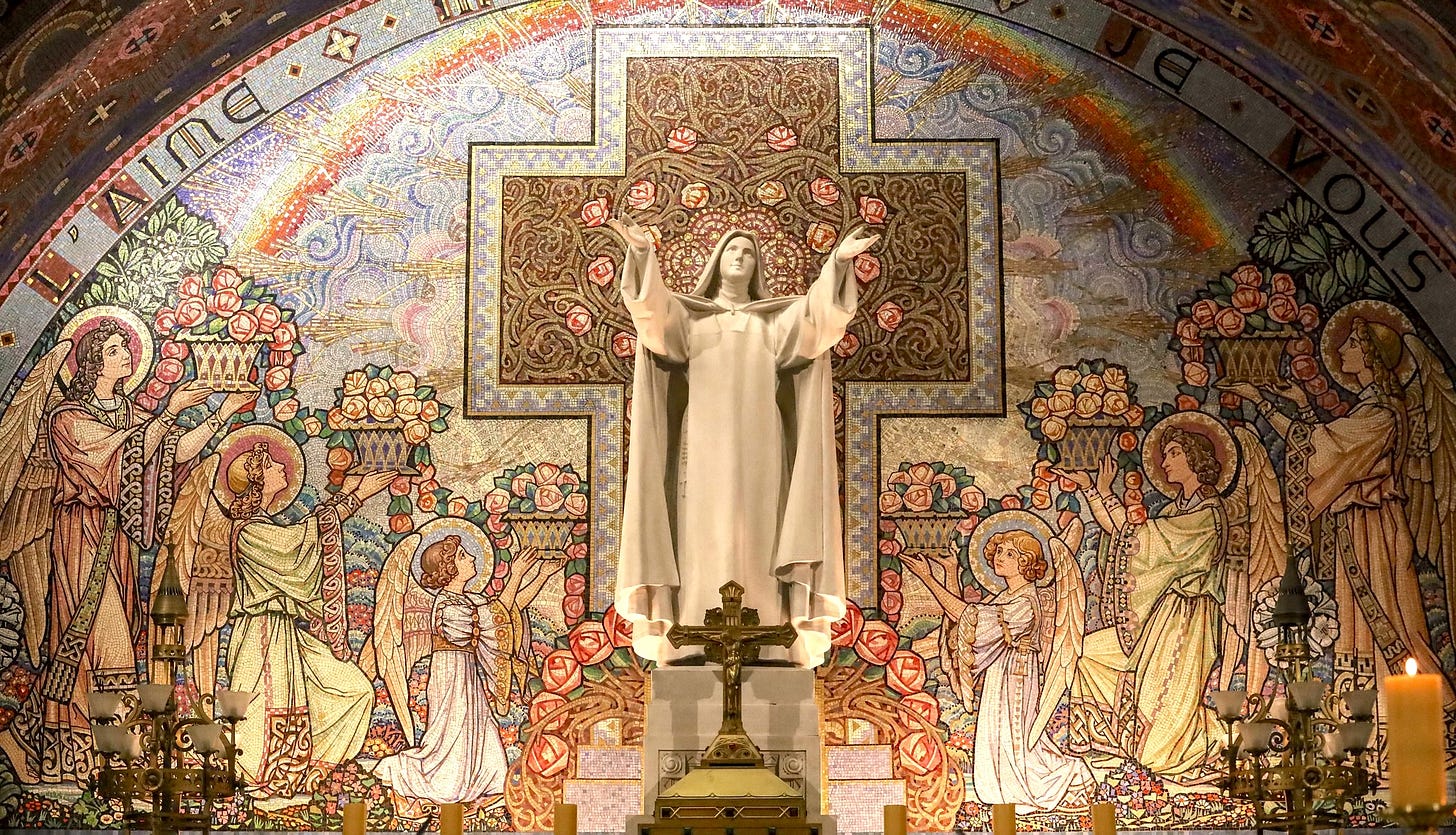

St Therese de l’Enfant Jesus

Mgr August Pierre Laveille

Trans. Fitzsimons, Benziger Bros., NY, 1928

Chapter XII, pp 302-318. Headings and some line breaks added.

What is “The Little Way”?

Before considering in its highest degree the love which was to consume the heart of Thérèse, it would seem that we should have completed the description of those virtues that sprang from it as from their principle.

Besides the faith of which, in spite of obscurities permitted by God, she gave such continual and such signal proofs, it would have been natural to note her invincible hope, her profound humility, her perfect abandonment into the hands of God.

It happens, however, that these virtues, completing as they do her spiritual endowment, form part of the ascetical method she has expounded in a manner that is altogether original. First of all, then, must be noted the place which humility, confidence in God, holy abandonment, zeal, and, above all, love itself, hold in this system. An exact knowledge of her spiritual doctrine, and the praise that Pope Benedict XV has given it, will show its high importance and even necessity. Following this theoretical examination, we shall study in the next chapter the practice in detail of these same virtues in the daily life of the Saint.

Not that the supernatural qualities already observed in Thérèse were strangers to her doctrine of perfection; but, excepting love, they were perhaps of lesser consequence thereto than those that are to occupy our attention at present.

Dating back to Thérèse’s childhood

From her very childhood, Thérèse had commenced to walk in this way. Only in 1895, however, did she begin to reveal its secret. In Chapter IX of the Histoire d’une Ame (Story of a Soul) she has described it to her Mother Prioress thus:

“You know, Mother, that I have always longed to be a Saint. But, alas! I have always felt, when comparing myself with the Saints, that there exists between them and me the same difference as we see in nature between a mountain with its summit hidden in the clouds and the grain of sand trodden under the feet of passers-by.

“Instead of being discouraged, I said to myself: ‘The good God would not inspire unattainable desires; I may, then, in spite of my littleness, aspire to sanctity. I cannot make myself greater; I must bear with myself just as I am with all my imperfections. But I wish to seek a way to heaven, a new way, very short, very straight, a little path. We live in a century of inventions. The trouble of walking upstairs exists no longer; in the houses of the rich a lift replaces the stairs. I, too, would like to find a lift to raise me to Jesus, for I am too little to ascend the steep steps of perfection.’

“Then I sought in the Holy Scriptures for some indication of this lift, the object of my desires, and I read these words from the mouth of Eternal Wisdom: ‘Whosoever is a little one, let him come to me.’1

“I then drew near to God, realizing well that I had found what I sought. Still desiring to know how He would deal with little ones, I enquired further, and found this: ‘As one whom the mother caresseth, so will I comfort you; you shall be carried at the breasts, and upon the knees they shall caress you.’”2

“Ah, never have more tender and melodious words gladdened my soul. Thine arms, O Jesus, form the lift which will raise me to heaven. For this I have no need of becoming greater; on the contrary, I must remain little and become even smaller. O my God, Thou hast surpassed my hopes, and I will sing Thy mercies: ‘Thou hast taught me, O God, from my youth, and till now I have declared Thy wondrous works; and unto old age will I continue to declare them.’”3

Here in a few sentences we have the exposition of a spiritual doctrine which, after having made of a weak child a great saint, continues each day to waken in the humblest souls virtues worthy of angels’ admiration.

In order, however, that they may prove a sure guide to those whom Thérèse wishes to lead, these lines call for brief commentary.

Roots in Holy Scripture and Fatherhood

And first, we note that nothing is more frequently and more expressly inculcated in Holy Scripture than the necessity of spiritual childhood. Let us add to the text quoted by Thérèse the clear and commanding words of the Master:

“Amen, I say to you, unless you be converted, and become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.”4

Nothing could be clearer; in order to be saved, and with all the more reason, in order to arrive at eminent sanctity, we must become as little children, we must clothe ourselves spiritually with the virtues of childhood.

What is it, if not littleness and weakness and the lack of all things, which inclines the child to rely with all confidence and simplicity on the affection of his parents, to look to them for everything with perfect abandonment?

This state of want, this radical powerlessness to be self-sufficing are precisely the dispositions which give the child real dominion over the father’s heart. Knowing by experience its parents’ unbounded anxiety for its welfare, the little one seeks refuge instinctively in their arms, abandoning itself to them without fear. The smaller and weaker the father sees his child to be, and the more he notices its need of support, and its ready confidence, the more does he open his heart to that child. It is not merely momentary protection that this loving abandonment obtains. Paternal love grows at each new service which the child demands, just as the latter’s affection expresses itself by new marks of tenderness at each succeeding act of kindness. Thus there takes place a sweet and touching interchange of love, founded originally on the weakness and insufficiency of the little one so tenderly cherished.

But if such be the history of a father’s heart, what shall we say of the immeasurable devotedness of the mother towards her new-born babe, who, without her aid, must droop and die? Is it not she, above all, who becomes more and more attached to her child in proportion to its weakness? What can be a surer means of gaining her heart than to make her realize the immense needs of this frail little creature?

Let us now compare these observations with the teaching of Holy Scripture. God is a father, and the burning ardour of His love surpasses all human tenderness. His charity exceeds, moreover, that of the most devoted of mothers here below, since, on the testimony of His prophet, if even the impossible should happen, that a mother forget her infant, yet never need we fear such abandonment on His part.5 It follows that the surest means of gaining His Heart is to remain or to become again a child, in His eyes, that is to say, to recognize our nothingness in His sight, to lay our poverty before Him, to make ourselves truly little in presence of His Majesty, confiding without fear in His sovereign goodness so that we may move Him to generosity towards us. We have here the initial lines of the way planned out by Sœur Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus, and the secret which she proposed to reveal to “little souls.”

The concrete actions of this method

This secret appears simple; it contains nothing which can inspire fear in the feeblest Christian heart. It is essential, however, to discern clearly the true signification of the actions enjoined by this method.

First, there is the recognition of our incapacity and poverty. But this can be recognized and at the same time hated, reviled. What is necessary is that we willingly proclaim our nothingness in regard to the greatness of the Almighty. In other words, the surest disposition to draw from the Father in heaven a kindly smile is humility of heart by which we really and truly love to see ourselves as we are, and look with joy into the depths of our lowliness.6

This disposition is, alas, comparatively rare, even amongst Christians. The greater number are, indeed, willing to admit their weakness, but only to a certain point. They credit themselves with real personal strength, on which they are content to rely while all goes well, only to fall into discouragement at the first serious obstacle they meet with. They have not understood that the child’s strength lies in its very weakness, since God is inclined to help His creatures in proportion to their recognition and humble avowal of their natural helplessness.

To these Thérèse gives an unequivocal lesson when she writes:

“In order to be raised to heaven in the arms of Jesus, I need not become greater; I must, on the contrary, remain little and even become smaller.”7

And again:

“What pleases Jesus in my little soul is to see me love my littleness and poverty, to see the unquestioning hope I have in His mercy.”8

She goes farther, and says:

“It is Jesus who has accomplished everything in me; I have done nothing but remain little and weak.”9

Let us, however, note henceforward that the workings of Jesus in the soul do not dispense from personal effort. The little child who is helped, supported, saved by its father must repay these benefits by active and generous love as far as it is able. We shall speak later of this necessary co-operation.

Poverty—but of what kind?

A second characteristic trait of spiritual childhood is poverty. The child possesses nothing of its own; everything belongs to its parents. But is it not precisely this absolute want of all things which moves the father to provide for every necessity, especially if the child is insistent in drawing attention to the excess of its misery?

We give to the little child who has nothing of its own precisely because it has nothing, because it realizes its poverty and pleads for pity. When this state of penury has ceased to exist through the child growing up and commencing to earn his own livelihood, the father, be he ever so affectionate, discontinues his bounty.

“Even amongst the poor,” observed Thérèse, “the little child is given what is necessary. But when it has grown up, the father is no longer inclined to continue his help, and says: ‘Work now; you are able to support yourself.’

“Well then,” she added, “it is so that I may never hear such words that I have not wished to grow up, feeling incapable of gaining for myself life eternal, for I have never been able to do anything by myself alone. I have always therefore remained little, occupying myself solely in gathering flowers of love and sacrifice and offering them to the good God for His pleasure.”10

The child, then, who wishes to obtain the help due to its tender years, must say to its father: “I am not able to do anything; be my strength. I have nothing; be my riches.”

In the same way, the soul will gain everything by possessing nothing and by looking to God for all. She must, however, accustom herself to await the coming of each day for the gifts thereof, asking nothing except what is needed at the present instant, because the grace required is, in God’s designs, an actual grace to be given at the opportune moment.

To realize this we have but to meditate on Thérèse’s example of supernatural indifference towards what the morrow may bring, as expressed in the following lines.

“What matters it, my Lord, if the future sombre be?

To pray Thee for the morrow—ah no, not thus my way;

Preserve my heart unstained, protect me lovingly

Just for to-day.”11

Moreover, the poor in spirit, when once in possession of God’s gifts, be they spiritual or corporeal, will guard against assuming any proprietorship over them, for they belong always to God, who has simply lent them and is free to take them back as He wills. In this also Thérèse, especially towards the end of her life, will be found a perfect model for imitation. “Now,” she wrote, “I have received the grace of being detached from the things of heart and spirit as well as from the goods of earth.”12

Finally, one who chooses the “little way” must be resigned to remaining poor all her life. By this also she will imitate the dear saint who, while multiplying her acts of virtue, did not concern herself with storing up merits for eternity, but laboured for Jesus alone, giving over to Him all her good works to “purchase souls.”

The following declarations of Sœur Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus will help wonderfully in the difficult task of interior despoliation, the fruits of which she extols.

“To love Jesus,” she says, “to be His victim of love, the more weak and miserable we are, the better disposed are we for the operations of this consuming and transforming love… The sole desire of being a victim suffices; we must, however, be always willing to remain poor and weak. Herein lies the difficulty, for where are the truly poor in spirit to be found?

“‘They must be sought for afar off,’ says the author of the Imitation… He does not say that they must be sought for amongst the great, but afar off—that is to say, in lowliness, in nothingness… Ah! let us remain far away from pomp; let us love our little- ness, let us love to feel nothing. Then shall we be poor in spirit, and Jesus will come to seek us, be we ever so far away. He will transform us into flames of love.”13

Confidence in God

Besides humility of heart and the spirit of poverty, something more is required. Confidence, unbounded, unwavering confidence in the merciful goodness of the heavenly Father is the infallible means of inclining His Divine Heart to compassion and bounty. With St. John of the Cross Thérèse repeated from her heart: “From the good God we obtain all that we hope for.”14

Besides, how can we refuse our confidence to that God who, having out of His gratuitous bounty created man, loved him even unto sacrifice on Calvary? How can we doubt the infinite mercy of Jesus, who has pardoned Magdalen, who opened paradise to the penitent thief, who prayed for His very executioners? To those who dwelt on the rigour of God’s justice in order to excite fear, Sœur Thérèse would reply with assurance:

“It is because He is just that God is also compassionate and full of tenderness, slow to punish and abounding in mercy, for He knows our frailty; He remembers that we are but dust.”15

The chief practical conclusion from this doctrine is that a soul initiated into the “little way” must confide in the divine mercy regarding past faults, however grave and multiplied they may have been, that she must look to the same mercy for the pardon of her daily falls. Has not Sœur Thérèse said that “the fault thus cast with filial confidence into the furnace of love is immediately and wholly consumed?”16

This confidence is also necessary in failure; the futility of human actions draws pity from the Divine Heart. It is equally required in darkness and aridity. The saint, who, towards the end of her life, experienced all these so poignantly, repeated in moments of direst distress:

“I turn to God and to all the saints, and I thank them in spite of everything. I believe they wish to see how far my confidence will go.”17

She requires that the care of the future be left with God, and in justifying that demand, she shows what her own practice was in this matter:

“The good God has always come to my assistance; He has led me by the hand from my tenderest years; I count upon Him…”18

In fine, she wished that no bounds be set to our hopes and desires of attaining to holiness, supporting her words by reference to the merciful omnipotence of “Him who being Power and Holiness itself would have but to take a soul in His arms and raise it up to Him in order to clothe it with His infinite merits and make it holy.”19 And, asserting more definitely the efficacy of confidence even in arriving at the highest perfection, she does not hesitate to add:

“If weak and imperfect souls like mine felt what I feel, not one of them would despair of reaching the summit of the mountain of love.”20

The soul who has chosen the “little way” will endeavour above all to imitate the child in its ingenuous and warm affection for its parents. She will try, as Thérèse charmingly says, to “win Jesus by caresses,” to lose no occasion of giving Him pleasure, to let slip no little sacrifice, act, or word which would serve to show our constant affection, not only to suffer but rejoice through love, to know how to smile for His sake always, in everything we do and suffer—such is the infallible way to obtain not only that we be regarded by Him with love, but that we be raised up in His paternal arms and pressed to His Heart.

Objections: this is not possible or the right way

Let it not be said that this love is inaccessible to a soul in its earthly exile. On the day of baptism it received the mysterious seed of Divine charity; its sole duty consists in tending and fostering that seed by personal and constant effort, helped on by Divine assistance.

It will be objected, perhaps, that love is “the crown of the spiritual edifice,” that it would be an illusion to commence where we should finish. Yes, perfection of love, it is true, should crown the edifice. But it is no less true that love should direct the whole construction. Let us begin through love, let us continue through love, and we shall see that no better worker than love can be found for the work of perfection. None other builds more quickly, none more solidly, more magnificently, or more beautifully, for love makes everything light and easy.

To him that loves, as St. Augustine remarks, nothing costs; or, if perchance something does cost in the doing, love rejoices thereat, and works with renewed ardour.21

The desire to give even more

We are in possession of Thérèse’s secret of advancing surely on the way of perfection. But the heart of a saint, when consumed by this love which penetrates and envelops it with inextinguishable flames, is not satisfied with devoting itself to Jesus on Calvary, and in the Sacred Host. It longs to give more, to give unceasingly, to give until it covers, if that were possible, the distance separating its poor and feeble love from the Infinite.

But a point is reached where it feels itself held back by the limitations of its nature. If union is to become more intimate still, and more perfect, God must intervene, and, in His liberality, act directly on that soul. That such intervention can take place, and that the history of the Church holds eminent examples of such intervention, Thérèse could have no doubt, she who had so often meditated on the riches of the Blessed Virgin’s soul, filled as it was from the moment of her creation with a marvellous plenitude of grace, she who had read with so much admiration and envy the account of the sudden transformation of the Apostles. Therefore, being unable to raise herself by her own strength to the most sweet and close intimacy with the Heart of Jesus, she had recourse in her weakness to the “Divine lift.”

She recalled the memories of her infancy; she saw herself as a little child vainly trying to climb unaided the stairs that led to her mother’s room. She remembered how her mother came at her call, extended her arms, and carried her in a few seconds to that sanctuary where her caresses soon calmed and reassured her child. Her mother’s arms had been her lift in reaching the first floor of her own home; the arms of Jesus, who is a thousand times more tender than any earthly mother, would carry her still more swiftly and surely to the happy resting-place amid the delights of pure love.

“Herein, we believe,” says Père Martin, “lies the chief originality of the ‘little way’ of childhood, making it truly a ‘new way, very short and straight’ to arrive at perfection. To place oneself in the hands of God, and in confidence, love, and abandonment, allow oneself to be carried by Him to the highest pinnacle of charity by means of perfect correspondence with His grace—such is the ‘little way.’ Thus it is God who does everything. As to the soul, it follows simply with docility the interior movements inspired by its Divine Bearer. It will rejoice simply in being carried in His all-powerful arms.

“Nevertheless, it is important to note that a soul which slumbers in indolent quietism cannot rejoice. The soul’s rest in the arms of God does not exclude vigilance. ‘I sleep, but my heart watcheth,’22 says the Spouse of the Canticles. ‘I sleep’ shows abandonment, ‘my heart watcheth’ portrays the soul’s activity and correspondence with grace. Even in the most perfect state of abandonment, this grace of activity continues. It does not suffice to surrender oneself once for all to the Divine dispensation. As the latter is unceasingly active, so must the soul be constant in its co-operation.

“The above remark was necessary in order to exclude erroneous interpretation. But, with that reservation, we can say definitely that when a soul has once taken its place in the Divine ‘lift,’ the only thing required by its heavenly Father is its unreserved surrender to His love to be wholly consumed therein, giving itself unresistingly into the hands of Providence to be led as He wills.”23

The question: Is this spiritual doctrine just for St Thérèse?

Such, then, as a whole, is the doctrine of perfection given by Sœur Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus. Was this doctrine intended exclusively for her own use, or are its fruits reserved for certain chosen souls resolved to follow the seraphic Carmelite in her upward flight, or again to ingenuous souls inclined by nature towards the happy simplicity of childhood? In other words, is the way of spiritual childhood optional for Christians in general?

The question does not even arise for those who remember the Gospel’s explicit invitation. What is capable of variation is the degree of love with which each soul will practise the virtues of the “little way”; all are not obliged, not even all the fervent, to make that offering to merciful Love which epitomizes Thérèse’s relations with Jesus.

But no Christian soul can be dispensed from practising these virtues which form an integral part of the “little way”: humility, the spirit of poverty, confidence, and filial love. To Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus belongs the incomparable merit, the everlasting glory of having, without endeavour to conceal difficulties, presented holiness in such an attractive light, of having shown it to be within the reach of every soul of goodwill, even to the lowliest and poorest.24

Papal teaching that it is for everyone

The praise with which the Sovereign Pontiff, Benedict XV, has honoured this method is of itself sufficient testimony in its favour. At the risk of insisting perhaps too much on the views already given, let us quote in part at least those pages which express the most explicit and authoritative judgement that could be desired in favour of religious teaching.

“There is no one who, knowing anything about the life of ‘little Thérèse,’ would not unite his voice to the great chorus proclaiming this life to be wholly characterized by the merits of Spiritual Childhood. There lies the ‘secret of holiness,’ not only for the French, but for the faithful throughout the entire world. We have, then, reason to hope that the example of the new French heroine will serve to increase the number of perfect Christians, not only of her own nation, but amongst all the sons of the Catholic Church.

“To gain this end, a right understanding of spiritual childhood is necessary. But is not today’s Decree, exalting as it does a fervent disciple of Carmel who attained to the heroism of perfection by the practice of virtues that spring from spiritual childhood, is not this Decree itself destined to spread abroad a correct idea of what spiritual childhood means?

“The harmony existing between the order of sense and that of spirit allows us to base the characteristics of spiritual childhood on the former. Observe a child just able to walk, who has not yet the use of speech. If molested by another of its own age or one stronger threatens it, or if it be frightened by some animal unexpectedly appearing, to whom does it run for safety, where does it seek refuge? In the arms of its mother, is it not? …

“Welcomed by her and pressed to her heart, all fears are set at rest, and heaving a sigh of which its little lungs seemed hardly capable, it regards courageously the object of recent alarm and trouble, and even incites it to fight, as though saying: ‘I have now a sure defender; safe in my mother’s arms I abandon myself to her care, assured not only of being protected against enemy attacks, but also of being treated in the way best suited to advance my physical development.’ So, likewise, is spiritual childhood fostered by confidence in God and trustful abandonment into His hands.

“It will be useful to consider the qualities of this spiritual childhood both as regards what it excludes and what it implies. Spiritual childhood excludes first the sentiment of pride in oneself, the presumption of expecting to attain by human means a supernatural end, and the deceptive fancy of being self-sufficient in the hour of danger and temptation.

“On the other hand, it supposes a lively faith in the existence of God, a practical acknowledgement of His power and mercy, confident recourse to Him who grants the grace to avoid all evil and obtain all good. Thus the qualities of this spiritual childhood are admirable, whether we consider their negative aspect or study them in their positive bearing, and we thereby understand why our Saviour Jesus Christ has laid it down as a necessary condition for gaining eternal life.

“One day the Saviour took a little child from the crowd, and showing him to His disciples, He said: ‘Amen I say to you, unless you be converted and become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.’25 O eloquent lesson, which destroyed the error and ambition of those who, looking on the kingdom of heaven as an earthly empire, desired to occupy the first places, or sought to be the greatest there. Quis, putas, major est in regno cœlorum?

“And as if to make it still more clear that pre-eminence in heaven will be the privilege of spiritual childhood, the Saviour continued in these terms: ‘Whosoever therefore shall humble himself and become like to this little child, he shall be the greater in the kingdom of heaven.’

“Another day certain mothers drew near and presented their children that He might touch them, and when the disciples would drive them away, Jesus said with indignation: ‘Suffer little children to come to Me and forbid them not; the kingdom of heaven is for such.’ And here as before He concluded: ‘Amen I say to you, whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child shall not enter into it.’ Quisquis non receperit regnum Dei velut parvulus, non intrabit in illud.26

“It is important to notice the force of these divine words, for the Son of God did not deem it sufficient to affirm positively that the kingdom of heaven is for children—Talium est enim regnum caelorum—or that he who will become as a little child shall be the greater in heaven, but He explicitly threatens exclusion from heaven for those who will not become like unto children.

“Now, when a master expounds a lesson under several different forms, does he not wish to signify by this multiplicity that he has that lesson especially at heart? If he seeks so earnestly by this means to inculcate it, it is that he desires by one or other expression to make it the more clearly understood. We must then conclude that the Divine Master was particularly anxious that His disciples should see in spiritual childhood the necessary condition for obtaining life eternal.

“Considering the insistence and force of this teaching, it would seem impossible to find a soul who would still neglect to follow the way of confidence and abandonment, all the more so, we repeat, since the divine words, not only in a general manner, but in express terms, declare this mode of life obligatory, even for those who have lost their first innocence. Some prefer to believe that the way of confidence and abandonment is reserved solely for ingenuous souls whom evil has not deprived of the grace of childhood. They do not conceive the possibility of spiritual childhood for those who have lost their first innocence.

“But do not the Divine Master’s words, Nisi conversi fueritis et efficiamini sicut parvuli, indicate to them the necessity of change and of work? Nisi conversi fueritis points out the change which must be effected in Christ’s disciples in order to become as little children once more. And who should once more become a child if not he who is so no longer? Nisi efficiamini sicut parvuli indicates the work, for we know that a man must work to become and appear what he has never been, or what he is not at present.

“But since a man must necessarily have been a child at one time, the words Nisi efficiamini sicut parvuli inculcate the obligation of work in order to regain the gifts of childhood. Any such thought as that of reassuming the appearance and helplessness of early years would be ridiculous; but it is not contrary to reason to find in the words of the Gospel the precept addressed alike to men of advanced years to return to the practice of spiritual childhood.

“During the course of the centuries, this teaching was to find increased support in the example of those who arrived at heroic Christian perfection precisely by the exercise of these virtues. Holy Church has ever extolled these examples in order to make the Master’s command better understood and more universally followed. To-day, again, she has no other end in view when she proclaims as heroic the virtues of Sœur Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus.”27

Impossible to improve upon this masterly exposition.

After thus outlining the theory proposed by the dear saint, we must now study its realization in her own life. How has she herself practised the virtues she declares essential to the “little way”? How has she finally delivered herself up as a victim to Merciful Love, abandoning herself wholly to God’s paternal providence?

We shall review these briefly, before recalling the circumstances which marked the end of her mortal life.

We will publish Mgr Laveille’s account of the realization of the little way in her life at a later date.

From Mgr August Pierre Laveille, St Therese de l’Enfant Jesus

Further Reading:

On St Thérèse of Lisieux:

St Thérèse of Lisieux – Story of a Soul

Mgr Laveille – The Life of St Thérèse of Lisieux

Fr Petitot – St. Thérèse of Lisieux – A Spiritual Renascence

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Prov ix. 4

Isaias lxvi 13.

Cf. Ps. lxx 18. Histoire d’une Ame, ch. ix, pp. 153-154.

Matt. xviii 3

Isaias xliii 25, 2

Sœur Thérèse has herself explained what she understands by this littleness so pleasing to God.

“To be little,” she says, “means not to attribute to self the virtues that one practises, believing oneself capable of anything; it means recognizing that the good God places this treasure of virtue in the hand of His little child to be used by him when he has need of it; but always it is God’s treasure. In fine, it means not being discouraged about our faults, for children fall often, but are too small to do themselves much harm.”

Cited in the Summarium of 1919, p. 260.

Histoire d’une Ame, ch. ix, p. 154.

Sixth letter to Sœur Marie du Sacré-Cœur.

Spirit of St Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus. She has expressed the same thought in the Histoire d’une Ame: “Because I was little and weak, Jesus gently stooped down to me, and instructed me in the secrets of His love” (p. 81).

Conseils et Souvenirs.

My Song of To-day.

Histoire d’une Ame, ch. x,

Sixth letter to Sœur Marie du Sacré-Cœur

Histoire d’une Ame, ch. xii, p. 240

Sixth letter to the missionaries.

Fifth letter to the missionaries.

Histoire d’une Ame, ch. xii, p. 236.

Ibid., p. 237.

Ibid., ch. iv, p. 55.

Ibid., ch. xi, p. 209.

G. Martin, La “petite voie” d’enfance spirituelle, p. 53.

Cant v 2

G. Martin, op. cit., cf. p. 69. The theory of ‘the little way’ of spiritual childhood that we have just given has been taken in part from this excellent work, the best undoubtedly that has been written up to the present on the ascetical doctrine of St Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus.

St Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus has had the singular privilege of presenting holiness under its truly Evangelical aspect, in divesting it of all the complications with which the human mind had, in the course of centuries, enveloped it. Referring to this, a learned theologian has lately said: “St Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus has cleared the way to heaven.” And an eminent prince of the Church: “What I admire in this little saint is her charming simplicity. She has excluded mathematics from our relations with God.”

Matt. xviii 3

Mark x 15.

Discourse of His Holiness Pope Benedict XV on the occasion of Promulgation of the Decree regarding the heroicity of her virtues, August 14, 1921.

His Holiness Pius XI was later to speak with no less praise of the “little way” in his homily at the canonization ceremony.

“We to-day conceive the hope of seeing spring up in the souls of Christ’s faithful a holy eagerness to acquire this evangelical childhood, which consists in feeling and acting under the empire of virtue as a child feels and acts in the natural order.

“If this way of spiritual childhood became general, who does not see how easily that reform of human society would take place which we set before us in the early days of our Pontificate and in promulgating this solemn Jubilee?

“We offer, then, as our own this prayer of the new saint, Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus, with which she terminates her precious Autobiography:

“‘O Jesus, we beseech Thee to cast Thy divine eyes upon a great number of little souls, and to choose out of this world a legion of little victims worthy of Thy love.’”—May 17, 1925.