Everything you've heard about Newman’s 'toast to conscience' is probably wrong

No other explanation of Cardinal John Henry Newman's comments about toasting 'conscience first, and the Pope afterwards' makes sense except this:

No other explanation of Cardinal John Henry Newman's comments about toasting 'conscience first, and the Pope afterwards' makes sense except this.

Everything which most people think or have been told about Cardinal Newman’s famous toast “to conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards” is probably wrong.

Newman’s remarks come at the end of a chapter of Newman’s Letter to the Duke of Norfolk (1875). This work was a defence of English Catholics against the charge that Vatican I rendered them the mindless slaves of a foreign prince (the pope) and that they were therefore disloyal and dangerous to the nation.

Newman’s book was polemical in nature. It was not welcomed by all Catholics, but the vast majority saw it as a successful vindication of the doctrine of papal infallibility in relation to the civil obedience of the Catholic population of the United Kingdom.

At the end of the chapter on conscience, Newman wrote:

“I add one remark. Certainly, if I am obliged to bring religion into after-dinner toasts, (which indeed does not seem quite the thing) I shall drink—to the Pope, if you please,—still, to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards.”1

Out of context, this passage might indeed suggest a reluctance to toast the pope along with support for modern liberalism.

Various admirers of Newman have tried to explain this comment, but their explanations never seemed convincing to this writer. On the contrary, they seemed to leave Newman vulnerable to accusations of disloyalty to the papacy and more.

As we shall see in this piece, this is most unfair, because this very extract proves the diametric opposite to be the case about Newman himself.

The significance of “The Loyal Toast”

This passage is sometimes approached from a purely theological, moral or philosophical angle, without regard for an ongoing controversy in England. This controversy seems to have already dated back centuries before “the Pope” became involved.

Those aware of this controversy would have found Newman’s comment to be a powerful and effective conclusion to his chapter. But it must be admitted introducing the matter of toasting the pope here has been very misleading for those with no knowledge of the controversy. This controversy revolves around “The Loyal Toast.”

At that time—as well as before, and since—the loyal toast was offered for the monarch, both at formal state functions and at private gatherings. Newman refers to this at the start of the next chapter of the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, Newman talks of “Church-of-Englandism, its cry being the dinner toast, ‘Church and king.’”2

The modern Debrett’s guide comments on this long-standing tradition:

“The first and principal loyal toast, as approved by The Queen, is ‘The Queen’. It is incorrect to use such forms as ‘I give you the loyal toast of Her Majesty The Queen’. To obtain the necessary silence, the toastmaster may say, without preamble, ‘Pray silence for ...’”3 (Emphasis added)

The historian Allan Michie explains the importance and prevalence of the loyal toast, as well as the particularity and formality of its ritual:

“The custom of drinking the loyal toast to the health of the monarch and members of his or her family, which is still invariably observed at all public and official dinners and in the messes of the fighting services in Britain and overseas, is a complicated national ritual with many variants.

“Even toasts have a long-established order of precedence and soon after her accession Elizabeth II approved that the future order of toasts in her reign should be:

The Queen

Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

Queen Mary

The Duke of Edinburgh

And the other members of the royal family.

“By custom, no one smokes in a formal dining room in Britain until the toast or toasts have been given.”4

We can see the importance of this toast when we consider that some offered an alternative toast to “The King over the Water,” as a means of signifying their loyalty to the Jacobite line of the Stuarts, rather than the existing monarch. Michie explains the history:

“Until early in this century finger bowls were never placed on the table when royalty was entertained. This was because in Georgian times those Jacobites who were secretly in sympathy with the banished Stuarts used to pass their glasses over the bowls before drinking a toast to the King, a covert allusion to ‘the royal exiles over the water.’ Edward VII, feeling that his house was by then firmly established on the throne, abolished the custom on his accession.”5

Omitting the loyal toast—or replacing it with the toast to someone other than the reigning monarch—was a serious matter, indicating disloyalty to the nation and to the crown.

To put it in perspective, it might be more or less comparable to how some people view the inclusion of the name of a false pope in the Canon of the Mass, or athletes “taking a knee” during the national anthem.

This is environment in which the controversy over “toasting the pope” took place.

Catholics begin toasting the Pope

At some point, Catholics in England began the practice of toasting the Pope.

In 1858, an article in Catholic periodical The Rambler dedicated a few passing paragraphs to this topic, which was then addressed at length in 1859.

The second article gave the following account of the phenomenon:

“When Catholics get together as Catholics, the first thing they look for is a convenient form of expressing their Catholic enthusiasm. When they dine together, they naturally adopt the dinner forms usual in England and allow their enthusiasm to express itself in toasts.”6

This gave rise to two problems, both addressed in these articles:

Irreverence towards the sacred

Political implications of toasting the Pope

Irreverence towards the sacred

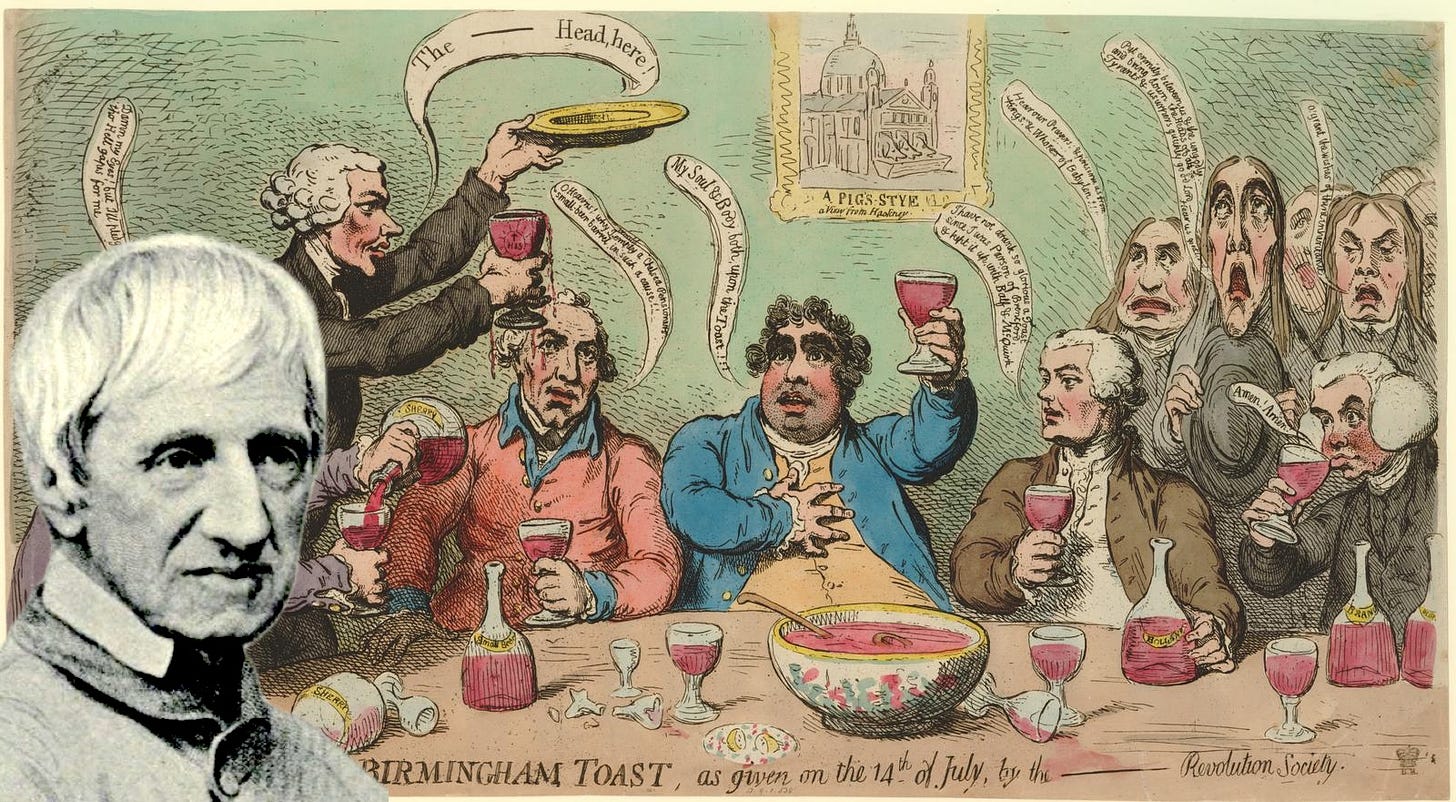

After-dinner toasts were often undignified, and perhaps quite different to how they are imagined today.

The Rambler refers to them as “bacchanalian,” with the toasts being “roared out,” accompanied (of course) with much drinking, resulting in “the flushed face, the quickened pulse, and excited brain of the dancing dervish.”7

Because of this, introducing religion and divine things into this setting was seen as vulgar and profane.

The Rambler seemed to think that society was becoming progressively refined, and that some practices which the author saw as vulgar—such as after-dinner toasts—would soon be abandoned. That author evidently did not foresee the progressive vulgarisation of our society, such that these practices would become the affectations of the pretentious.

(Nor, incidentally, did he foresee that the “muscular Christianity” which he derided in that article would, in our day, become an online trend and be seen as a necessary solution to the crisis in the Church.)

It is ironic that those who complain about Newman’s apparent reluctance to toast the pope (itself an unfair characterisation), as if it is obvious that he should be enthusiastic about toasting the pope after dinner, implicitly take upon themselves The Rambler’s censures; namely, that these critics are themselves so vulgar and unrefined as to think that rowdy after-dinner toasts are an obviously appropriate place to introduce religion and divine things.

By contrast, even as an Anglican, Newman had preached on a related matter—namely, the lack of reverence shown towards sacred things, including those who discussed religion “over their cups”:

“I have alluded to these schools of religion, to show how widely a feeling must be spread which such contrary classes of men have in common. Now, what they agree in is this: in considering God as simply a God of love, not of awe and reverence also,—the one meaning by love benevolence, and the other mercy; and in consequence neither the one nor the other regard Almighty God with fear; and the signs of want of fear in both the one and the other, which I proposed to point out, are such as the following. […]

“Another instance of want of fear, is the bold and unscrupulous way in which men speak of the Holy Trinity and the Mystery of the Divine Nature. They use sacred terms and phrases, should occasion occur, in a rude and abrupt way, and discuss points of doctrine concerning the All-holy and Eternal, even (if I may without irreverence state it) over their cups, perhaps arguing against them, as if He were such a one as themselves.”8

This same concern about the irreverence towards sacred things is present throughout the two Rambler articles, as well as extract from the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, when Newman comments that bringing religion into after-dinner toasts “indeed does not seem quite the thing.”

This is a different sentiment to what we find today, with Theology on Tap sessions, and the sub-Chestertonian idea of the public house as one of the ten loci theologici. Perhaps standards can and have changed in this department, and we all do it. But because of this, it does not seem proper to be critiquing our forebears for a reserve and reverence which we have lost.

The political implications of toasting the Pope

As the practice of the after-dinner toast to the pope spread, the inevitable question was whether “The Pope” would replace “The Queen,” or whether it would precede or follow her.

Each option led to significant problems, in terms of what they implied, as detailed in the 1859 article in The Rambler.

These difficulties only increased when non-Catholics began hearing about these toasts—especially as the Pope’s health was frequently drunk before the Queen’s.

According to The Rambler, this practice of toasting the pope also aroused “the indignation of Protestants,” which in turn prompted “so many trivial quarrels.”

Catholics were emerging from a long period of suppression: while many were prepared to offend the religious majority when necessary or inevitable, they also saw it as wantonly imprudent to be aggravating the religious majority when unnecessary or avoidable. The situation was still somewhat precarious, offence to Protestants could damage the Catholic cause, and jeopardise the Church’s mission of saving souls.

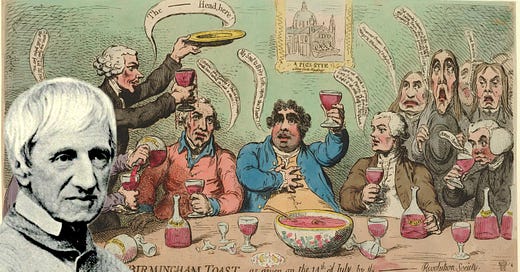

As an example of the situation, Cardinal Wiseman was satirised by Punch in 1858:

“The Ultramontane Toastmaster

“At the dinner which the priests gave at Ballynasloe to Cardinal Wiseman, the usual disloyal toast [to the Pope] was drunk, and the usual loyal toast [to the Queen] omitted.

“As the assembly, with the exception of two persons, consisted entirely of ecclesiastics, the disaffection evidenced by that omission may be despised.

“[But] The people of Ireland will drink the Queen’s health in spite of their priests, who, at least when that toast is proposed, are unable, though they may wish, to deny the cup to the laity.”

‘THE PRIESTS AND ‘THE LADIES.’

‘What do the Priests,’ asked Dennis, ‘mean,

Toasting the Pope and not the Queen?’

‘Bedad, they mean to drink,’ said Thady,

‘Our Scarlet, not our Sovereign Lady.’9

Given the timing, it may be that the two articles in The Rambler were intended as a defence of Cardinal Wiseman, whilst also being critical of the practice in itself. It is even possible that Newman himself was involved with this defence. He was involved with The Rambler around this time, taking over the editorship a few months after the second article. Wilfred Ward writes:

“It seemed, however, to be a choice between the Review dying and his taking the editorship. Under the deepest sense of duty, and after a good deal of hesitation and consultation with the fathers of the Oratory, after praying long to know God’s Will, he accepted it in March 1859.

“He did so at the wish of Bishop Ullathorne and Cardinal Wiseman, and after explicitly writing to W. G. Ward, who with Oakeley was temporary editor of the Dublin, that he contemplated no kind of rivalry with that periodical.

“His letters show that he regarded the undertaking as a duty—a most important one, though in some ways a most unwelcome one. And he seems to have felt somewhat bitterly that his motives were little appreciated. He was credited with wishing to exercise influence, to propagate his own ideas.”10

Although it is not possible to say definitively whether Newman was involved with these articles, their themes are very similar to what he discusses in the relevant chapter of the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk.

Newman’s treatment of conscience

Let us return to the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, published in response to Prime Minister William Gladstone. Gladstone was a prominent Anglican politician, having been Prime Minister between 1868 and 1874, and would later serve a further three terms in the years between 1880 and 1894.

We have already considered these matters at length elsewhere, and so will limit ourselves to the necessary context for the final comment on toasting the pope.

In the relevant chapter, Newman defines conscience with reference to St Thomas Aquinas, whilst making clear that conscience had no bearing on propositions per se, or with the attainment of religious truth:

“I observe that conscience is not a judgment upon any speculative truth, any abstract doctrine, but bears immediately on conduct, on something to be done or not done.

“‘Conscience,’ says St. Thomas, ‘is the practical judgment or dictate of reason, by which we judge what hic et nunc is to be done as being good, or to be avoided as evil.’

“Hence conscience cannot come into direct collision with the Church’s or the Pope’s infallibility; which is engaged in general propositions, and in the condemnation of particular and given errors.’”11

Newman states that one cannot address the subject of conscience without starting with God and the divine and natural law. He rejects faulty, liberal views of conscience, including that which has come to be attributed to him on the basis of this article.

As mentioned, the thrust of Gladstone’s work was that Vatican I and papal infallibility meant that Catholics had replaced conscience with the will of the reigning pope, had become his mental slaves, were absolved from personal responsibility, and were incapable of being trustworthy subjects of any state.

Such ideas were no doubt greatly encouraged by factors such as some Catholics replacing the loyal toast to the Queen with the “disloyal” toast to the Pope, which made it appear to Englishmen that Catholics were making themselves the subjects of a foreign, hostile prince.

Newman addresses various aspects of these problems, emphasising the primacy of the spiritual over the temporal, and conscience’s need for an external, objective divine authority. He also refuted the idea that Catholics had abandoned conscience, and that they were essentially foreign subjects, incapable of loyalty to the nation.

Proceeding from there, Newman turns the argument around on his opponent.

First, he affirms Pope Pius IX and Gregory XVI’s condemnations of modern ideas of liberty of conscience:

“It seems a light epithet for the Pope to use, when he calls such a doctrine of [liberty of] conscience deliramentum: of all conceivable absurdities it is the wildest and most stupid.”12

He continues:

“Both Popes [Gregory XVI and Pius IX] certainly scoff at the so-called “liberty of conscience,” but there is no scoffing of any Pope, in formal documents addressed to the faithful at large, at that most serious doctrine, the right and the duty of following that Divine Authority, the voice of conscience, on which in truth the Church herself is built.

“So indeed it is; did the Pope speak against Conscience in the true sense of the word, he would commit a suicidal act. He would be cutting the ground from under his feet. His very mission is to proclaim the moral law, and to protect and strengthen that ‘Light which enlighteneth every man that cometh into the world.’

“On the law of conscience and its sacredness are founded both his authority in theory and his power in fact.”13

In other words, he argued that Catholics hold conscience to be fundamental for all loyalty and submission to all rightful authority, whether it be civil or spiritual. He explained that, once one is confronted with the motives of credibility, it is conscience which prescribes the act of faith and submission to the Church and the Pope.

Conclusion—Just how badly Newman has been misunderstood

Having seen the nature of the controversy over toasting the Pope, and having briefly considered Newman’s comments about conscience and the question of whether Catholics could be good citizens or not, we can see the injustice that Newman’s name has suffered due to this passage being misunderstood.

The Rambler article in 1859 sets out the multi-pronged challenge posed by the practice of “toasting the pope”. Should Catholics…

Toast the Pope first and Queen second—and thereby indicate disloyalty to the nation?

Toast the Queen first, and the Pope second—and thereby indicate disloyalty to the Church?

Withdraw the toast to the Pope—and thereby indicate disloyalty to the Church by omission?

Unless we have grasped this, and the way in which it represents Gladstone’s whole challenge to English Catholics, we are simply hearing one side of a telephone conversation, and very liable to misunderstand.

But once the prongs of challenge are understood, we can understand Newman’s response in the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk. He seems to be answering an unspoken test, or trick question, emblematic of Gladstone’ challenge. Would English Catholics take the “Disloyal Toast” to the Pope after dinner, and thus show your inability to be loyal Englishmen?

Newman responds by turning the presuppositions upside-down. We could be minded here of Our Lord’s response, when he is asked whether it was lawful to pay tribute to Caesar.

He states that he will indeed join a toast to the Pope, but that he will toast conscience first—not because he has some distorted idea of conscience, but because it is in conscience that all loyalty to the Church, Pope and the nation finds its sure foundation.

It is conscience, duly formed, which commands us to submit to both temporal and spiritual authority, in their proper order.

Some have mistaken this passage for a description of a real event, in which (they think) Newman was tactlessly trying to teach people a lesson about the papacy, bringing them down a notch, and demonstrating his loyalty to erroneous ideas about liberty of conscience and of religion.

In fact, Newman himself brought up the matter of the toast. Far from showing unwillingness or reluctance to toast the Pope, Newman affirms his willingness to join such a toast—despite it being seen as vulgar and “not quite the thing,” and regardless of whether it looks bad, or means that he is perceived as disloyal to the nation.

Given his volunteering of the topic, and his expressed readiness to incur the opprobrium of the establishment for such a toast, it is unjust and incorrect to suggest that this passage was a demonstration of his unwillingness or reluctance to recognise the rights of the Pope.

Further, this sadly common interpretation makes no sense in the context of the chapter. The framing of such an interpretation of this passage is all wrong, and also abstracted from the reality, controversy and conventions around toasts which would have been obvious at the time.

On the contrary, Newman’s comment was a sort of parable, summarising the chapter, affirming his loyalty to the Pope in the face of Protestants who were harassing English Catholics about their supposed allegiance to a foreign prince, and confounding the false dichotomy between being a good Catholic and a loyal subject of the Crown.

In light of all this, we shall conclude with Pope St Pius X’s words about Cardinal Newman, regarding modernists and liberals who pointed to him as their precursor. These words apply equally well to some of his traditionalist critics:

“[T]hose who were accustomed to abusing his name and deceiving the ignorant should henceforth cease doing so.”14

Published in anticipation of the 179th anniversary of Newman’s reception into the Catholic Church.

Further Reading:

See also The WM Review’s Newman Archive

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

John Henry Newman, Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, 1875, p 261. Published in Certain Difficulties felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching Considered, Vol. II. Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1900. Available at https://www.newmanreader.org/works/anglicans/volume2/gladstone/section5.html

Newman 264

“The Loyal Toast”, Debrett’s. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20160307234624/http://www.debretts.com/forms-address/hierarchies/official-functions/loyal-toast

Allan A. Michie, God Save the Queen: A Modern Monarchy—What it is and what it does, p 99-100. Sloane Associates, Inc. New York, 1953. Available at Internet Archive. An amusing anecdote immediately follows:

“Some years ago the suggestion was made that the toast could only be drunk in wine and that anything else was a tacit insult to the sovereign, which led the Lord Chamberlain's office to rule, solemnly, that ‘wine is most usual, but it can be tea, coffee, or cocoa, according to the whim of the people concerned,’ and Edward VII, no teetotaler, let it be known that he nevertheless considered the toast to his health just as loyal if drunk in water.”

Michie, 99. The above text omits another amusing anecdote, showing the graciousness of Edward VII:

“Not long afterwards a foreign potentate being entertained at Edward's dinner table innocently lifted his finger bowl and drank from it. Edward, who made a reputation as a diplomatic monarch by his friendly relations with his European neighbors, was equal to the occasion. Without a moment's hesitation he drank from his own finger bowl, a precedent that all his guests followed for the remainder of that meal.”

'Toasting the Pope' in The Rambler, January 1859, New Series Vol. XI, Part LXI, pp 56.

Ibid., 61.

John Henry Newman, ‘Reverence, a Belief in God’s Presence’, In Parochial and Plain Sermons, Vol V. Page 970 of the Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 1997, pp 967-966. Available at: https://newmanreader.org/works/parochial/volume5/sermon2.html

Included in ‘Modern Humorists’, in The Dublin Review, Vol. XLVIII, May and August, p 145. Thomas Richardson and Son, London 1860, pp 107-149.

Wilfrid Ward, The Life of John Henry Cardinal Newman based on his private journals and correspondence, Vol I. pp 480-1. (And for UK readers). Longmans, Green and Co, London 1912.

Newman 256

Newman 275.

Newman 252-3

Pope St Pius X, March 1908. Available at https://newmanreader.org/canonization/popes/acta10mar08.html – which gives the following reference: English translation, provided by Michael Davies, also included in Davies’ Lead Kindly Light: The Life of John Henry Newman, Neumann Press, 2001.