Why we are mourning Queen Elizabeth II’s death

“We don’t have to consider anything she did – but what she was.”

Photo by Samuel Regan-Asante on Unsplash. The Changing of the Guard, a few days after the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

There are some persons – particularly among those who lament various laws that have been passed during Queen Elizabeth II’s reign – that are not sure what to make of this period of national mourning. Some are even scandalised by it.

So why exactly are we mourning? What should we make of the solemnity and grandeur of it all?

Or – to put it another way – what could we make of it?

To answer these questions, let’s start by considering the teaching of Holy Scripture about power and civil authority, and those who bear it.

Holy Scripture

Our Lord tells us:

“Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s; and to God, the things that are God’s.”

Matthew 22.21

And he says to Pontius Pilate:

“Thou shouldst not have any power against me, unless it were given thee from above.”

John 19.11

In his Epistle to the Romans, St Paul writes:

“[T]here is no power but from God: and those that are ordained of God.”

Romans 13.1

He then applies this to civil authorities:

“Princes are not a terror to the good work, but to the evil […] For he is God’s minister to thee, for good. But if thou do that which is evil, fear: for he beareth not the sword in vain. For he is God’s minister: an avenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil.”

Romans 13.3-4

These injunctions of submission, reverence and honour towards civil authorities run through the New Testament. In his First Epistle, St Peter tells us:

“Be ye subject therefore to every human creature for God’s sake: whether it be to the king as excelling, or to governors as sent by him for the punishment of evildoers and for the praise of the good.

“For so is the will of God, that by doing well you may put to silence the ignorance of foolish men: as free and not as making liberty a cloak for malice, but as the servants of God.

“Honour all men. Love the brotherhood. Fear God. Honour the king.”

1 Peter 2.13-17

St Paul writes to Titus:

“Admonish them to be subject to princes and powers, to obey at a word, to be ready to every good work.”

Titus 3.1

Similarly, we see St Paul calling for us to pray for the monarch.

“I desire therefore, first of all, that supplications, prayers, intercessions and thanksgivings be made for all men: for kings and for all that are in high station: that we may lead a quiet and a peaceable life in all piety and chastity.

“For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Saviour, who will have all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.”

1 Tim 2.1-3

And lest anyone think that these texts can justify a tyranny in which the Monarch’s whim is law, let’s also recall the words of the St Peter and the Apostles, which we can apply to evil commands:

“We ought to obey God rather than men.”

Acts 5.29

Most importantly of all, let’s remember that civil society is obliged to govern in accordance with the natural law, and to recognise the sovereignty of Christ the King.

Subscribe to stay in touch:

St Thomas and Law

St Thomas Aquinas summarises these scriptural texts:

“The king is indeed the minister of God in governing the people, as the Apostle says: There is no authority except from God (Rom 13:1) and God’s minister is the servant of God to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer (Rom 13:4). And in the Book of Wisdom, kings are described as being ministers of God (Wis 6:5).”[1]

So civil authority is a good thing. And what do we find at the heart of government and civil authority?

Law.

The purpose of the civil authority is to order society towards peace and the common good, in accordance with reason – in other words, to govern in accordance with law. St Thomas defines a law as:

“An ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated.”[2]

Even if our liberties are being progressively eroded, those which we continue to enjoy come from being ruled in accordance with law.

This brings us to the question of who can make law. St Thomas tells us:

“A law, properly speaking, regards first and foremost the order to the common good. Now to order anything to the common good, belongs either to the whole people, or to someone who is the viceregent of the whole people.

“And therefore the making of a law belongs either to the whole people or to a public personage who has care of the whole people: since in all other matters the directing of anything to the end concerns him to whom the end belongs.”[3]

God can and does bestow civil authority and the right to govern and to make laws in different ways in different states.[4] Leo XIII acknowledges that the chief power may be held by one, many or all – and that the recipient or recipients of this power might be designated by inheritance, law or election. But to return and summarise again the Scriptural texts, he continues:

“[A]s regards political power, the Church rightly teaches that it comes from God, for it finds this clearly testified in the sacred Scriptures and in the monuments of antiquity; besides, no other doctrine can be conceived which is more agreeable to reason, or more in accord with the safety of both princes and peoples.”[5]

St Thomas also lists the various types of law according to the various forms of government, including monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy and democracy.[6] But he concludes with this comment:

“[T]here is a form of government made up of all these, and which is the best: and in this respect we have law sanctioned by the ‘Lords and Commons,’ as stated by Isidore.”[7]

This is our form of government in England, and the United Kingdom. Laws are made with the sanction of Lords and Commons – but always with Royal Assent.

The Crown is crucial to civil authority in our nation. There are different and disputed understandings of what exactly “The Crown” means. A recent Parliamentary briefing gave a range of ideas, including one legal scholar saying that “the Crown ‘means simply the Queen’”, and King George VI is quoted making a similar point.

This will suffice for our purposes, because this is not an essay proposing to resolve legal debates, nor to be speaking in precise constitutional terms.[8]

The supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom is “The Crown-in-Parliament” (the Monarch, together with the House of Commons and the House of Lords), and there are no laws without both the Crown and Parliament.

With regards to the judicial system, the Crown is referred to as the “Fount of Justice.” The briefing already mentioned quotes Martin Loughlin:

“All jurisdiction is […] exercised in the name of the Queen, and all judges derive their authority from her commission. Every breach of the peace is a transgression against the Queen. She alone has the authority to prosecute criminals; when sentence is passed, she alone can remit the punishment.”[9]

We can see these ideas elsewhere: for example, until 8 September 2022 the UK Government was properly called “Her Majesty’s Government”, and many of the powers it exercises are based on Royal Prerogatives.

Even if these things are treated as merely theoretical and ceremonial by some, civil authority in our nation is exercised by and in the name of one source – which must, in turn, receive its authority directly and immediately from God.

The Late Queen

It was therefore Queen Elizabeth II who received this power from God, and “had the care of the whole people,” in the sense described above.

Did she exercise the power which she received? One might answer in the negative: over the centuries, the exercise of many important prerogatives of the British Crown have been delegated to ministers and so on, or only exercised according to their advice. Similarly, Her Late Majesty never refused Royal Assent to any proposed law – and some argue that she does not even have the power to do so (a debate which we shall not enter here).[10]

On the other hand, one might answer in affirmative: it remained her authority which was exercised, through these ministers and delegates. The exercise of her power was, in many cases, limited by constitutional convention – but the Crown remained the principle of this authority, and no-one else shared the unique privilege of receiving this civil authority, directly and immediately from God.

No-one else – until her death, when the Crown passed immediately to her son and heir, Charles our King.

Like her, he has received his authority directly from God. But unlike the body of her Late Majesty lying in her coffin, King Charles is our living monarch – in whom is vested civil authority, exercised through the various organs of state. Each such exercise now derives its power and force from him.

There are those who despise our monarchy because of evils which our government has committed in its name. There are also those who fear King Charles’ politics in particular.

But while these things are important, they are not what we have in view here. To repeat, the point is that civil authority in our land is that of the Crown – which, in turn, comes from God.

These are not really supernatural matters – but they nonetheless call for reverence.

Reverence

As Her Late Majesty was called to be principle of civil authority, we can hold her to have been “anointed” in a figurative sense – even if we give no weight to Anglican oils and the Anglican rite of anointing itself.

We treat the bodies of deceased Catholics with reverence, knowing that they were washed in Baptism, anointed in Confirmation and fed with the Holy Eucharist; and in these cases, our reverence is based on a supernatural motive.

In a similar way – based on natural, civic motives – it is fitting to treat the “anointed” body of our late Queen with reverence.

In this period of mourning – and solely for the purposes of what we are considering here – it does not matter whether we approve of what she allowed to happen during her reign. It does not matter whether we approve of the constraints and exercise of constitutional conventions. Our reverence is not conditional on whether she lived a good life or died in God’s grace. It does not matter whether or not we liked or admired her.

Among the matters above, some are enormously important – but the legitimacy of this period of mourning does not depend on them. These matters do not change the fact that we are burying an anointed body, which not long ago was the seat and principle of authority in our nation.

We need not see ourselves, necessarily, to be honouring Her Late Majesty for what she did – but for what she was.

Some of our fellow Catholics abroad might be scandalised by all this, for various reasons. It is true that some of the more extravagant and sentimental outpourings of emotion by the public are perhaps the result of religion’s decline in our nation. The now-expected conformity of corporations in signalling their grief is very dreary and hollow.

But – in principle – there is no threat to the true religion in a period of mourning, nor is there an opposition between our sacred and natural, civic duties. The body of the late Queen is being given civic honours, not religious honours.

Perhaps this will help us all understand the meaning behind the reverence and honour given to her coffin like a quasi-sacred relic. This is seen in the great numbers waiting to visit her coffin in Westminster Hall – and most impressively visible in the parades, and honours shown by our military – carrying, escorting, and saluting, with such great pathos, the coffin of our late Sovereign and their late Commander-in-Chief.

The late Queen’s body is definitively not a sacred relic. But if we value authority, order, law and liberty, then it is right and proper to honour the mortal remains of she who was their principle during her reign – and in a sense, embodied them – and who received her authority directly and immediately from God.

Sentimentality

We should certainly avoid any silly, sentimental excesses in this period – along with any of the Anglican worship that accompanies the mourning.

We should retain hold of Catholic principles: and one of these principles is the inappropriateness of public (and publicly-advertised) Requiem Masses for non-Catholics. Upon the death of Queen Victoria, Cardinal Vaughan wrote a letter to be read in all of his churches:

“The death of Her Most Gracious Majesty, after a prosperous reign of over 63 years, throws the whole of the British Empire into grief and mourning. […]

“None will mourn more sincerely than Catholics the loss of ‘the Good Queen’. […]

“Of public religious services for the dead the Catholic Church knows of none but such as she has instituted for the souls of her own children. For them the Requiem Mass, the Solemn Absolution, and the Catholic Funeral Office, form the only Memorial Service for the dead in her liturgy.

“No one would feel it to be right that, in our grief, we should so far forget ourselves or the proprieties due to her deceased Majesty and to the official position she filled, as even to appear to claim her as member of our Church, which we should be doing were we to perform in her behalf religious rites that are exclusively applicable to deceased Catholics. Of other rites for the dead the Church has none.

“At the same time we may remind you that it is lawful to those who believe that any persons have departed out of this life in union with the Soul of the Church, though not in her external communion, to offer privately prayers and good works for their release from purgatory. The Church herself forms no judgment on the matter which must remain the secret between God and the individual soul.”[11]

Clearly the elaborate public Requiem Masses for Her Late Majesty, lamentably proposed by some, are out of the question; and the justifications produced are risible. She was not a Catholic, and that should be the end of it.

But Cardinal Vaughan continues:

“What then can we do? Everywhere a deep sentiment of loyalty and patriotism is swelling within the heart of the Catholic community in England, and seeking for some outward expression. Gladly and eagerly shall we join in the purely civil and social mourning, as in the civil honours that will be generously offered by the nation to the memory of such a Queen. Where there are church bells they will be tolled in sign of mourning, and the national flag may be run up half-mast, either within or without the precincts of our churches.

“We fully and acutely share in the national sorrow and the anxiety inseparable from such a period. We trust and pray that the noble traditions established by the Mother will be carried on and perfected by her Son. The attachment of Catholics to the Throne and the Dynasty are beyond suspicion.

“We proceed, then, to prescribe, in order that the Divine blessing may rest upon the successor to the Throne, upon the nation, and upon ourselves, the recitation, in the Mass, of the collect, “Deus, Refugium nostrum” until further notice, tamquam pro re gravi.”[12]

In other words – while there are some who want nothing to do with the British Monarchy – those who are unsure or conflicted about this period should have any qualms whatsoever entering into what Cardinal Vaughan called “the national sorrow,” whether it be through watching the parades, the visiting the coffin in Westminster, or whatever else.

Nor – so long as we do not participate in any non-Catholic religious activities – need we feel any scruple or guilt about honouring and mourning Queen Elizabeth II, whatever any of us might think of her reign or those that have governed in her name.

Conclusion

It is true that we could have a different form of government – and some think that a different form would be better. Perhaps the good things we have under law would be the same under a different constitution, or if civil authority came from a different source.

But in fact we do not have a different form of government. We have this form of government, in which the civil authority which gives us these good things is derived from the Monarch, who in turn receives it from God.

This isn’t to say that we must somehow feel “grateful” to her, even for our civil liberties and rights as subjects; nor to pretend that everything about her reign was perfect. To repeat, for these purposes, we do not need to see ourselves as honouring her for what she did for us, but for what she was for us – our anointed Sovereign, and the actual source of civil authority in our nation.

For all the reasons given here, there can be no shame in honouring the body of our late Queen. And there can be no shame in honouring and praying for her successor, His Majesty King Charles III – and wishing him well for his reign.

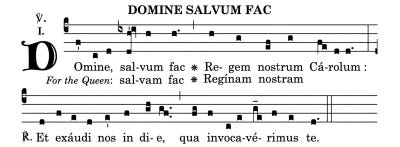

The collect to which Cardinal Vaughan refers is below, along with the Missal’s Collect for the King, and the antiphon which we sing for King Charles every Sunday after the principal Mass.

Those who fear that King Charles III will advance certain agendas should recall that we cannot expect any help from God if we do not ask for it.

May Her Late Majesty rest in peace.

God save the King!

Further Reading

NB: As Amazon associates, The WM Review receives a small commission on purchases made with Amazon links.

The WM Review – Why ignorance and prejudice are a dangerous mix – Cardinal Newman and the British Constitution

Sir John Fortescue’s On the Laws and Governance of England (and for UK readers), published in the sixteenth century, with frequent reference to St Thomas Aquinas.

St Thomas Aquinas – On Kingship. Despite the title, this is about more than just Kingship: it also deals with the purpose of civil authority in itself. In Opuscula I, from the Aquinas Institute (UK readers) and online at Aquinas.cc

Aristotle – Politics (and for UK readers and online)

Fr Edward Cahill – Framework of a Christian State (and for UK readers and online)

Mgr Paul F. Glenn – Sociology

Prayers

Deus, refugium nostrum

O God, our refuge and strength, who art the author of mercy, hearken to the pious prayers of thy church, and grant that what we ask with faith, we may effectually obtain. Through our Lord.

Quaesumus, omnipotens Deus

We beseech thee, O almighty God, that thy servant Charles our King, who by thy mercy has undertaken the government of this realm, may advance in all virtues, so that being meetly adorned therewith, he may avoid the evils of vices and merit to come unto thee, who art the way, the truth and the life. Through our Lord.

Source: The Society of St Bede

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing our articles free for everyone. If you have benefitted from our content please do consider supporting us financially.

A small monthly donation, or a one-time donation, helps ensure we can keep writing and sharing at no cost to readers. Thank you!

Single Gifts

Monthly Gifts

Subscribe to stay in touch:

Follow on Twitter and Telegram:

[1] St Thomas Aquinas, On Kingship, Chapter 8, available in Opuscula I, Aquinas Institute, 2018 (and for UK readers). Available online at https://aquinas.cc/la/en/~DeRegno.BookI.C8

[2] St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I-II, Q90 A4. (and for UK readers)

[3] ST, I-II, Q90 A3.

[4] Pope Leo XIII taught in Diuturnum: “5. Indeed, very many men of more recent times, walking in the footsteps of those who in a former age assumed to themselves the name of philosophers, say that all power comes from the people; so that those who exercise it in the State do so not as their own, but as delegated to them by the people, and that, by this rule, it can be revoked by the will of the very people by whom it was delegated. But from these, Catholics dissent, who affirm that the right to rule is from God, as from a natural and necessary principle.

6. It is of importance, however, to remark in this place that those who may be placed over the State may in certain cases be chosen by the will and decision of the multitude, without opposition to or impugning of the Catholic doctrine. And by this choice, in truth, the ruler is designated, but the rights of ruling are not thereby conferred. Nor is the authority delegated to him, but the person by whom it is to be exercised is determined upon.

7. There is no question here respecting forms of government, for there is no reason why the Church should not approve of the chief power being held by one man or by more, provided only it be just, and that it tend to the common advantage. Wherefore, so long as justice be respected, the people are not hindered from choosing for themselves that form of government which suits best either their own disposition, or the institutions and customs of their ancestors.

Encyclical Diuturnum, 1881, available at: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/leo13/l13civ.htm

[5] Leo XIII, Encyclical Diuturnum, 1881, n. 8, available at: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/leo13/l13civ.htm

[6] ST I-II Q95 A4

[7] Ibid.

[8] “The terms ‘the sovereign’ or ‘monarch’ and ‘the Crown’ are related but have separate meanings. The Crown encompasses both the monarch and the government. It is vested in the Queen, but in general its functions are exercised by Ministers of the Crown accountable to the UK Parliament or the three devolved legislatures.”

David Torrance, The Crown and the constitution, House of Commons Library, 4 February 2022, p 6. Available at https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8885/CBP-8885.pdf

[9] Martin Loughlin, “The State, the Crown and the Law” in M. Sunkin and S. Payne, The Nature of the

Crown (and for UK readers), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p 58. Quoted in Torrance 46.

[10] To repeat: this is an essay explaining motives for reverence towards the Monarch, not an explanation of the British Constitution.

[11] Letter from Herbert Cardinal Vaughan, 1901. Available at https://fsspx.uk/en/news-events/news/death-queen-76405

[12] Ibid.